Erich Heckel

Döbein, 1883-Radolfzell, 1970

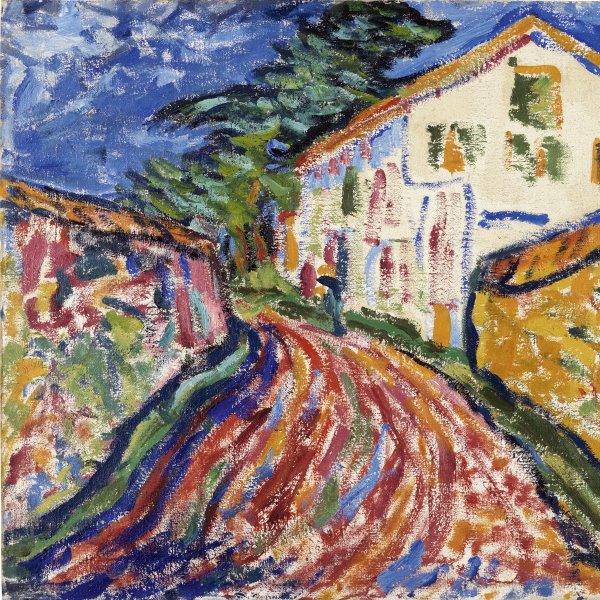

The German painter and engraver Erich Heckel was one of the founders of the Expressionist group Die Brücke (The Bridge) in Dresden and one of its most active members. He received painting and drawing classes in Chemnitz, where he met Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In 1904 the two of them moved to Dresden to study architecture at the Technische Hochschule, where they coincided with Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Fritz Bleyl. After abandoning their technical studies for painting, in June 1905 they established Die Brücke, of which Heckel acted as the unifying force and organiser. That year he had the chance to see original Van Gogh paintings at Dresden’s Galerie Arnold for the first time. Both Heckel and the rest of the group were fascinated by the art of the Dutch painter, whose influence became evident in their works until 1910. In the summer of 1907 Heckel paid his first trip with Schmidt-Rottluff to Dangast on the North Sea coast, where his style achieved maturity. In spring 1909 he travelled to Italy and spent the summer with Kirchner and Pechstein at the Moritzburg Lakes near Dresden. Like the rest of the members of Die Brücke, in 1911 he moved to Berlin, where the group split up shortly afterwards. During the First World War he worked as a volunteer with a medical unit in Belgium and later joined the revolutionary Novembergruppe. From 1922 to 1923 he worked on a mural cycle entitled Stages of Existence now in the Angermuseum in Erfurt.

When the Nazis came to power Heckel’s works were confiscated and seventeen of them were displayed in the sadly famous exhibition of Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art). The air raids on Berlin in 1944 completely destroyed his studio and many of his works. After the war was over he taught at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Karlsruhe from 1949 to 1955. He spent his last years in retirement in Hemmenhofen, near Radolfzell, by Lake Constance, where he died.

Heckel’s initial Expressionist style, true to the guidelines established by Die Brücke, was always centred on landscape with or without figures. He also produced many woodcuts of great formal simplification. During the 1920s his forms moved closer to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), and colour gradually gave way to a greater emphasis on lettering. During his final years he returned to an Expressionistic type of painting that was less aggressive and violent in form tha that of his early period.

When the Nazis came to power Heckel’s works were confiscated and seventeen of them were displayed in the sadly famous exhibition of Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art). The air raids on Berlin in 1944 completely destroyed his studio and many of his works. After the war was over he taught at the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Karlsruhe from 1949 to 1955. He spent his last years in retirement in Hemmenhofen, near Radolfzell, by Lake Constance, where he died.

Heckel’s initial Expressionist style, true to the guidelines established by Die Brücke, was always centred on landscape with or without figures. He also produced many woodcuts of great formal simplification. During the 1920s his forms moved closer to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), and colour gradually gave way to a greater emphasis on lettering. During his final years he returned to an Expressionistic type of painting that was less aggressive and violent in form tha that of his early period.