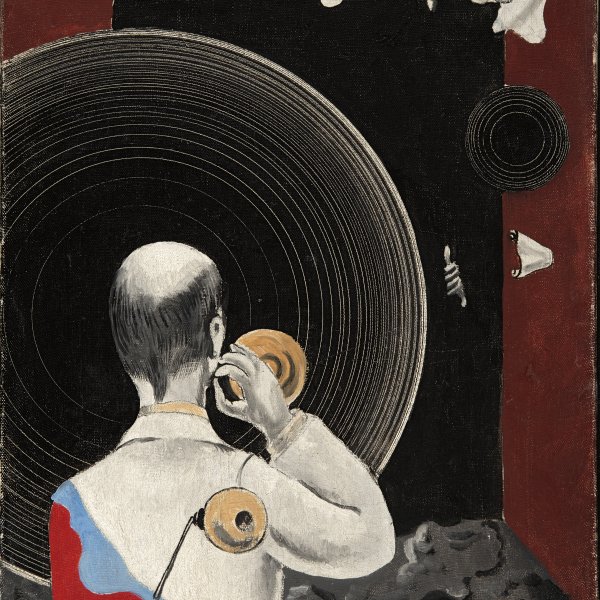

Catalan Peasant with a Guitar is one of a series of paintings produced after Miró’s first visit to Paris in 1920 and his subsequent exposure to the work of Dadaist and Surrealist poets and artists. From that moment on, the artist began to simplify his compositions in a process that gradually led him to abandon external reality in favour of a peculiar language of signs. Miró was strongly drawn to rural Catalonia, and he often used the figure of the Catalan peasant as a key feature in many of his canvases. Here, the stylised figure of the peasant wearing his characteristic red cap or barretina is portrayed full length, its sharp outlines contrasting starkly with the intense-blue background that dominates the painting, eliminating any spatial reference.

Joan Miró first travelled to Paris at the end of February 1920 with the aim of organising an exhibition through the mediation of his friend the gallery owner Josep Dalmau. In the French capital Miró, who had hardly ever left Barcelona, met Picasso and felt a powerful fascination for the Paris art scene: “This Paris has shaken me up completely. Positively, I feel kissed, like on raw flesh, by all this sweetness here, ” he wrote to his friend Ràfols. These would be the crucial years in his artistic career, in which, encouraged by the Surrealist experiences and the influence of the poetry he read, he broke with external reality and his work evolved from pictorial figuration to sign language. In addition to the influence of the Surrealist artists and poets, Tomàs Llorens mentions “the impact of Klee, ” whom he discovered in Paris about 1923. Miró himself always recognised these roots unequivocally: “Klee enabled me to see that a single spot, a spiral, even a dot, could form the subject of a painting, just as much as a face, a landscape or a monument.”

Catalan Landscape (The Hunter), painted while Miró was in Montroig in the summer of 1923, marked the first step in this new artistic direction. The main figure in the scene, the hunter, is a peasant clad in a barretina, the typical cap worn by Catalan commonfolk, who developed into the isolated figure in the series of Catalan peasants executed during the following months. In this set of oil paintings Miró repeated the schematised depiction of the figure with a barretina with some variations, setting it against neutral blue or yellow backgrounds. In these grounds Miró created a flowing space where the signs into which he projected his imagination drifted. As Rosalind Krauss has studied, Miró found in the grounds of colour without perspective a non-Cubist manner of doing away with the distinction between surface and depth. In a testimony quoted by Margit Rowell, Miró made his intentions clear: “I escaped into the absolute. I wanted my spots to seem open to the magnetic appeal of the void [...]. I was very interested in the void, in perfect emptiness. I put it into my pale and scumbled grounds, and my linear gestures on top were the signs of my dream progression.”

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Catalan Peasant with a Guitar belongs to this series on the theme of the Catalan peasant that Joan Miró painted in Paris and Montroig between March 1924 and the summer of 1925. As Jacques Dupin states, these works, which are so closely related to his rural past, would be a stepping stone to the oneiric paintings of the second half of the 1920s. Tomàs Llorens has recently stressed the importance of Catalonia to Miró, which he reconciled with his own intellectual background and the Surrealist avant-garde language.

The sequence Miró followed when painting the series of Peasants has been interpreted as a progressive simplification of the scene, from the more detailed versions until almost arriving at the desired void. The latest research — particularly that of Christopher Green— shows that we cannot speak of a linear evolution but rather of an alternation between the desire to fill in and the desire to empty the picture space, a method that his friend the anthropologist Michel Leiris compared to the meditation practices of Tibetan monks. We now know that Miró began the series with one of the more simplified versions, the Head of a Catalan Peasant in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, in which the hunter figure from the Catalan Landscape is isolated against the same yellow background. It was no doubt followed by the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Catalan Peasant with a Guitar, which shows the same person, this time full length, against a nocturnal Prussian blue background. The desire to add signs came later with the versions in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh and the former collection of César de Haucke. Miró ended the cycle, accentuating the initial simplification, with the most ethereal and bare image, the painting now in the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.

There are varied and thought-provoking interpretations of the meaning of this Catalan peasant: some authors see it as a political statement against the persecution of Catalan nationalism during the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera; others provide esoteric readings related to the Cabbala, which Miró used as a fertile source of poetic metaphors; Rosa María Malet has linked this depiction with Que vlo-ve?, the main character in a short story by Apollinaire, one of Miró’s favourite poets; and Christopher Green wonders if it might not perhaps be one of the imaginary self-portraits of which the artist was so fond. The fact is that in a painting so richly infused with poetic and literary images and with a mythology shaped from such personal signs, a combination of several readings is possible.

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.