My name is Susana Moliner Delgado. I was born on 2 February 1980, at 20:20, or so I always wanted to believe. I grew up in Madrid with a father from a proud working-class neighbourhood in Barcelona who really matured during the summers he spent in a small village in the interior of Castellón, and a mother born and raised in the city of Tétouan in Morocco.

From the very beginning, I was lucky enough to inhabit the outer edges, to-ing and fro-ing across the Strait of Gibraltar, where I could enjoy the chebakia (traditional Moroccan pastries) that family friends would give us at the end of Ramadan, the aromas on shopping trips to the medina quarter, and not understanding everything to know you were at home.

While studying politics at the Complutense University in Madrid, I really learned by helping my mother put together and produce tours for musicians who, in the 1990s, wanted to label as world music or ethnic music (oops!) Gnawa rhythms, Tibetan trumpets, the sounds of the zawya of Tangier, the voices of the women of the Andalusí orchestra in Tétouan, the rattles of the Bubi of Equatorial Guinea, the rhythms of Cuban santería, the corridos of the southern United States, the Senegalese sabar and the jazz of Cameroon with Manu Dibango. People from the south who, when they came to play, always visited our house and who made the stage their home at every concert they played.

After a year on Erasmus in Geneva, I finished my degree and worked as a waitress in Dublin, completed a post-grad in international cooperation and spent two years in Bordeaux, surviving from scholarship to scholarship in the visual arts sector. In all of those places, I orchestrated homes, subconsciously ignoring the fleeting nature of my stay and always trying to transcend and to bind forever the families I met.

In 2009 I was awarded a cultural scholarship from AECID, the Spanish international cooperation agency, and they sent me to the Embassy of Spain in Bamako. At this point, my life and my home took an about-turn.

When my stay in Bamako came to an end, with much nostalgie, to the extent that so much of that city has stayed with me, I didn’t know how I could return to Europe with all the lessons I had learned every day, so I looked for a way to keep my head turned south and found a job in a neighbourhood cultural centre in the city of Dakar, a place that tried to articulate digital artistic practices with citizens, connecting with artists and creators from the entire sub-region of West Africa and the diaspora. This experience helped me reflect on what we understand as art and its practical application for life from other perspectives.

In 2011, the 15M movement took over my city, coinciding with me finding my new home in Senegal. While I tried to connect with Madrid through the office wifi connection, which was desperately slow, the Y’en a Marre movement emerged in which several colleagues were involved, sharing slogans and squares, resonating like a common world between Dakar and Madrid.

During this time, within the framework of the common events that began to break out, and which I inhabited with all their potential and contradictions, the project, programme and framework of Grigri was beginning to take shape. The word grigri is used in West Africa to name magical objects, and it was the name of the totem I saw every morning on the way to work at the embassy in Bamako, on the taxi journey with my dear friend and therapist Armé, from the neighbourhood of Badalabougou.

Susana Moliner

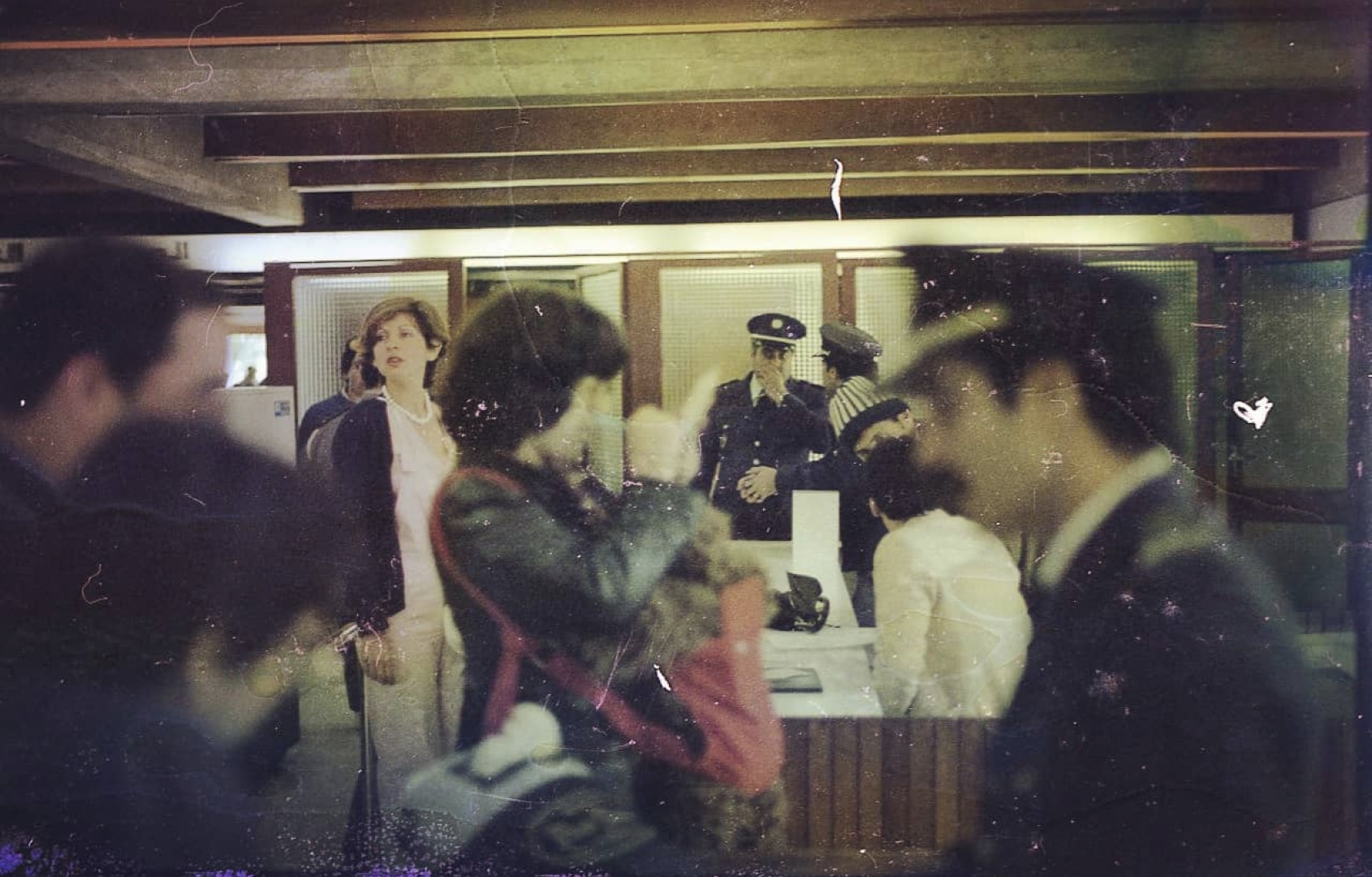

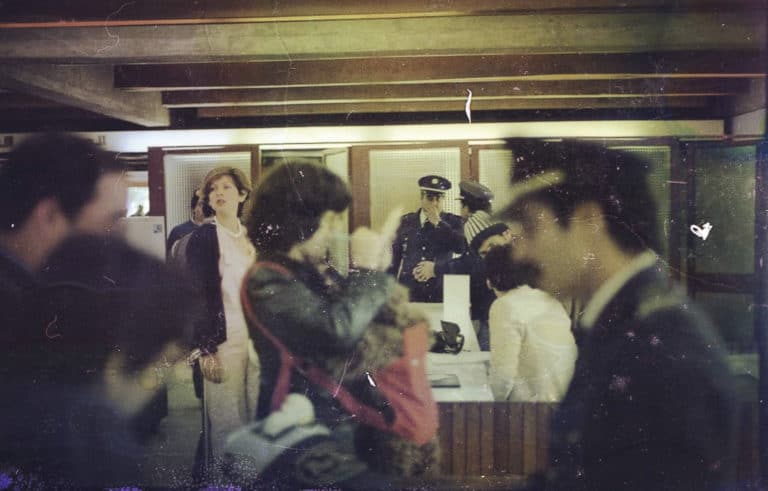

My mother and I (in the baby carrier) at passport control in Tangier airport.

It was a word that seemed to me the best way to describe and materialise those situations that are capable of transcending and opening further possibilities yet to be determined; an invisible framework producing new subjectivities, without prejudices or preconceived ideas of what something “should be” to “be original” from whatever part of the world; a commitment to inhabit the now as home and to let things happen that might decentre us so we can imagine other futures yet to come.

When I returned definitively to Madrid in 2016, along with a team of incredible people I launched the Grigri Pixel workshops, through which we have tried to share questions about the city from the experience of groups, creators and artists from African cities and their diaspora. It is a cooperation project that aims to reverse expert logics and bring the flavours of the south, to share strategies on how to make the city more habitable. We have explored the worlds of the invisible, the common, small technologies to produce energy, the right to a city and, last year, hospitality as an attempt to answer questions like:

What turns us into “neighbours”?

What agreements can we reach to be able to recognise ourselves in collective shared identities and from plural and inclusive senses of belonging?

How can we symbolically and materially formalise the commitment and mutual recognition with others, with our neighbourhood and city?

What conditions do we need to exist to create communities of destination rather than of origin?

How can we generate welcoming everyday spaces and hospitable neighbourhoods but also plural and inclusive identities? How can we make the neighbourhood or the city a common home?

The grigri protector we saw every morning on the way to work.

My dear Armé, taxi driver from the neighbourhood where I lived in Bamako, with a shea nut and his flamboyant map-of-Mali shirt.

During the 2019 edition of this programme, we wanted to share these questions with citizens through a series of actions in collaboration with SERCADE and Medialab Prado, including a conversation between Marina Garcés and Felwine Sarr, a workshop that took us to Niamey, and finally an event in Madrid bringing together artists and creators from Senegal, Burkina Faso, Niger, Morocco and Mozambique.

Our ongoing mission is to rethink the notion of home and activate hospitality not as a moral obligation but as an opportunity for learning and transformation in relation to the shared present and future we want to inhabit.

And here we are today at Grigri Projects, working to continue mulling over how, from the perspective of artistic practices and collectives, we can make it possible to “reach, receive and decide” words and actions to re-politicise the practice of hospitality offered by Marina Garcés in the conversation we organised in a square and which I also shared in one of the first sessions at the Museo Thyssen.

And to finish, here at Grigri Projects we have created and implemented projects like Cocinar Madrid, Haciendo Plaza and Templete Fantástico, as well as curatorial proposals like África Light (in Bordeaux, Bamako and Dakar), Côte à Côte (Rabat and Sardinia), Wekalet Nehna-We Agencia (Alexandria) and Privatisation d’un espace par son ciel (Dakar), also assisting with citizens’ laboratory programmes like Fuencarral Experimenta, attempting at all times to place the focus on the procedural part and the creation of community that these initiatives are capable of generating.

The fact is that we like to cook cities, re-charm neighbourhoods and activate and connect the knowledges that arise from the margins. Pretexts, always, to make a home.

Participant in the Y’en a Marre movement

Participant in the Y’en a Marre movement