To Amsterdam

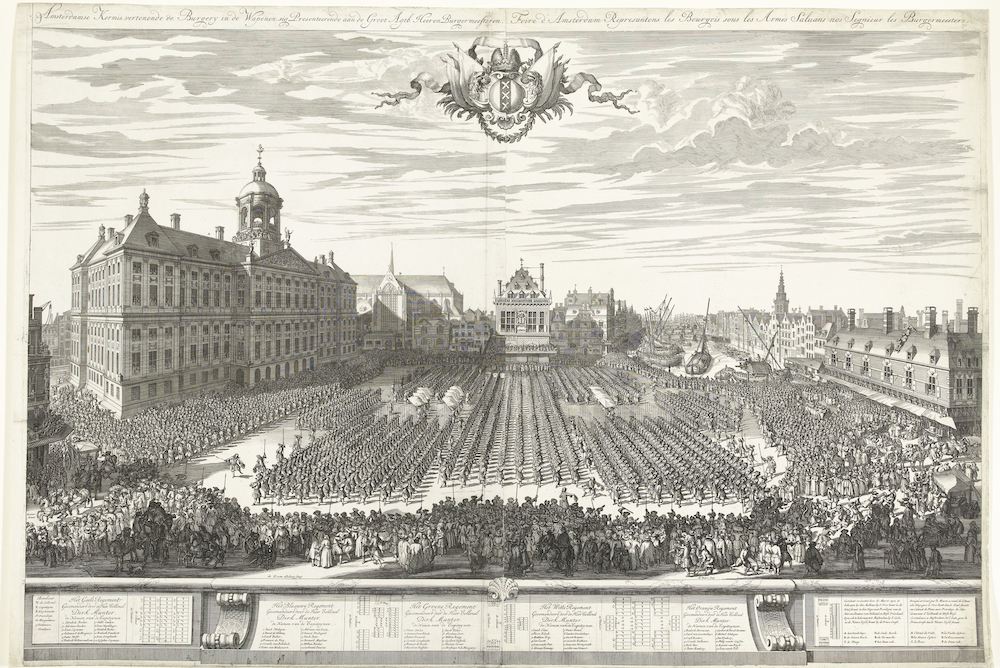

Daniël Marot (I), Dam Square, Amsterdam, 1686

Rijksmuseum

Hendrik Geun, Urban Landscape, 1782

Rijksmuseum

Benjamin Brecknell Turner (attributed), View of the Keizersgracht, 1857

Rijksmuseum

View of the Rijksmuseum, circa 1900

Amsterdam, like every city in the world, has two narratives: the official and the unofficial. The unofficial narrative is woven by citizens as they go about their daily lives, while the official story is the one impressed upon our minds as the result of a social construct on which a group of people have agreed.

For instance, the most famous city in the Netherlands is often presented to foreigners as an open, cosmopolitan, tolerant town, as the city of canals, of tall, narrow buildings, of cyclists, museums, tulips and cheese-filled broodjes (bread rolls).

To understand the origins of the narrative and imagery surrounding Amsterdam, we must travel back to the 17th century, the Dutch Golden Age, when the city became a major international trade hub on a par with London in the 18th and 19th centuries or New York in the 20th. Dutch merchants developed trade relations with the Far East; their navy founded overseas communities like New Amsterdam, on the island of Manhattan; and many foreigners came to live in the Netherlands. This was also a time of great cultural and scientific advances and relative political stability, enabling Amsterdam to emerge as a unique, proud city eager to share its way of life with the world.

Claes Jansz. Visscher (II), View of Amsterdam, 1611

Rijksmuseum

The museum work The Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal with the Flower Market, Amsterdam (1686), painted by Gerrit Adriaensz. Berckheyde, is a testament to this period and its official narrative, as it portrays the urban environs of the most important and iconic building of that era: the town hall (now the royal palace).

The history of Amsterdam’s development is complex and irregular. Established in the 13th century around a small fishing village, the urban centre did not begin to expand significantly until the early 17th century, when new canals, residences and government buildings were constructed.

It was also then that the citizens decided to build a new centre of municipal government worthy of their flourishing city. The plans were drawn up by the famous architect and painter Jacob van Campen, and construction began on 28 October 1648, the same year that the Peace of Münster ended hostilities between Spain and the United Provinces of the Netherlands.

Campen’s architectural design, which some hailed as the eighth wonder of the world, featured impressive facades measuring 79 metres wide by 55 metres tall that aimed to convey the grandeur and power of the city.

Gerrit Adriaensz. Berckheyde

The Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal with the Flower Market, Amsterdam, 1686

Oil on canvas. 53.7 x 63.9 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

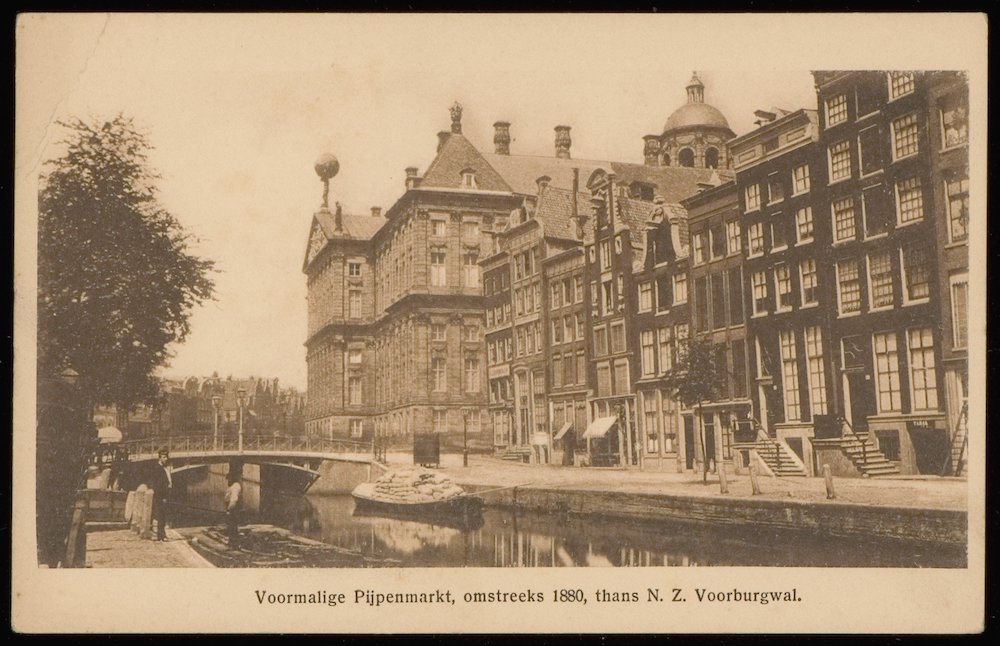

On the right bank of the canal painted by Berckheyde, in addition to the imposing town hall, we also see the typical Dutch brick townhouses. These buildings were quite tall and narrow because land was hard to come by in the city centre, and property taxes were steep.

In those days, Dutch houses usually served two purposes. The attics were used to store goods while the family resided on the lower levels, uniting business and home life under the same roof.

View of the flower market and Royal Palace, Amsterdam, 1824

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

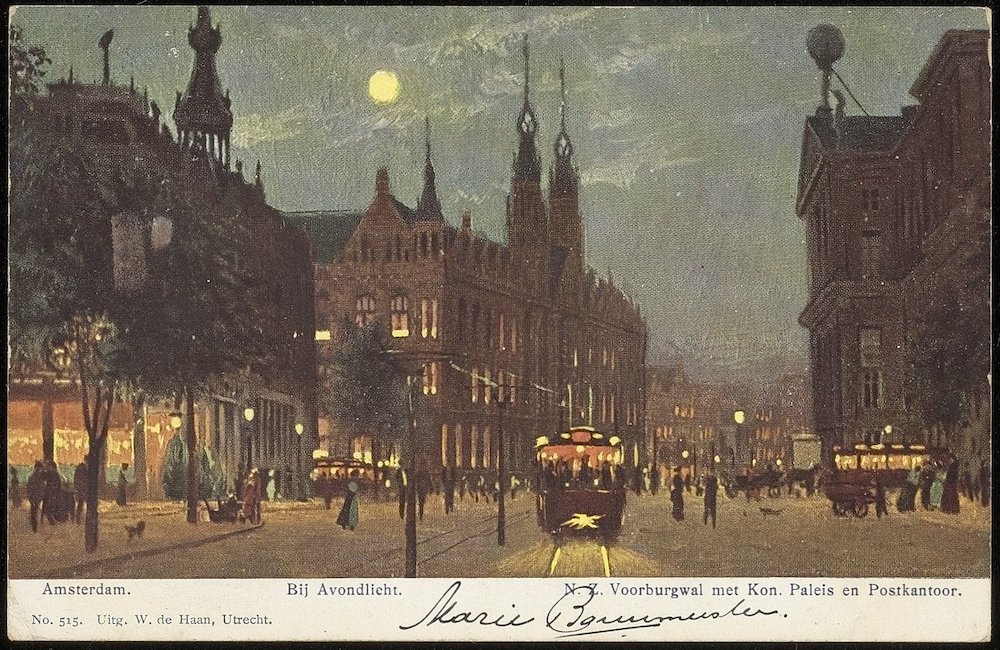

Postcard of the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 1900

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Postcard of the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 1900

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Postcard of the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 1905

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Postcard of the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 1910

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Postcard of the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 1915

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

Postcard of the Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal, 1920

Stadsarchief Amsterdam

To experience present-day Amsterdam, we must surrender to its sounds, the hustle and bustle of the people in its streets and squares; feel the allure of meeting people and discovering things we didn’t even know existed; be open to social interaction and new ideas. And despite the changes that have transpired over the years, in order to truly surrender to Amsterdam, we have to harness the architectural spirit of the Dutch Golden Age, because this is one of the few European cities that have managed to make their past the basis of their urban future.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza