To Arles

“I saw a magnificent and very strange effect this evening. A very large boat laden with coal on the Rhône, moored at the quay. Seen from above it was all glistening and wet from a shower; the water was a white yellow and clouded pearl-grey, the sky lilac and an orange strip in the west, the town violet. On the boat, small workmen, blue and dirty white, were coming and going. Carrying the cargo ashore.” – Letter from Vincent van Gogh to his brother Theo, written at Arles in August 1888

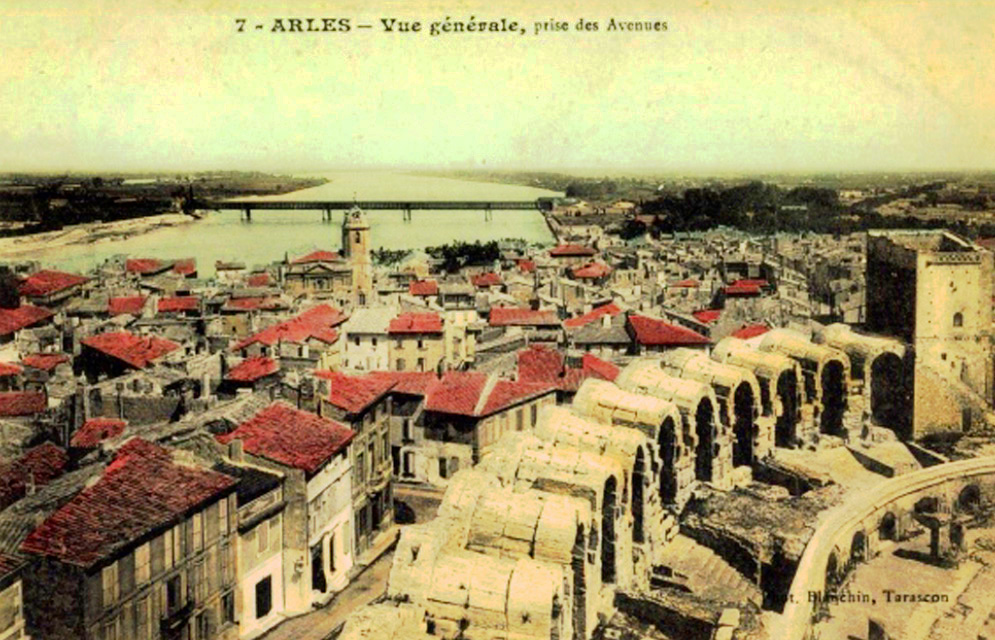

Postcard of Arles

Séraphin-Médéric Mieusement

Forum of Arles

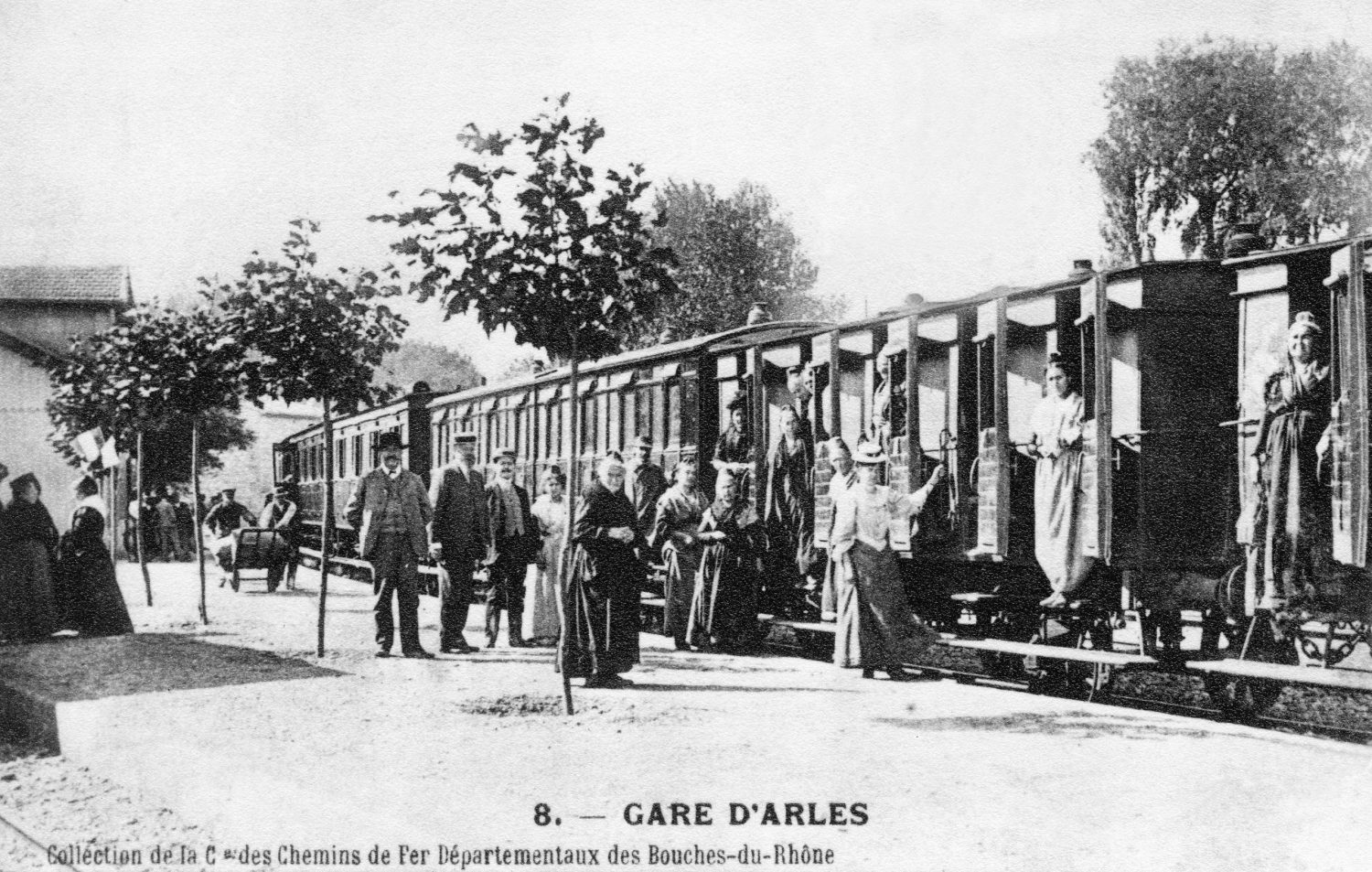

Arles Railway Station

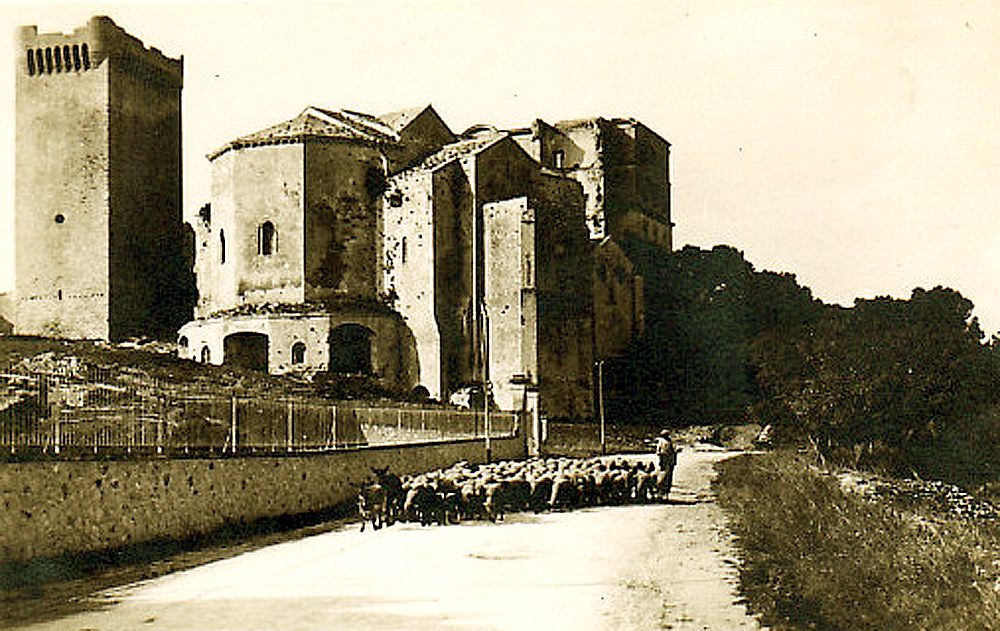

Montmajour Abbey. Arles

In 1888 Vincent van Gogh left Paris, where he had evolved towards a palette influenced by Impressionism, and headed for the south of France, seeking the light and warmth of Arles. Although he went there with the dream of forming a community of artists around himself, he ended up painting alone most of the time, except for the brief time he spent working alongside Paul Gauguin. Van Gogh was always a painter on a quest to find himself, a wandering soul guided by chromatic impressions and the thrill of glorifying and drawing attention to the harsh existence of the ordinary. An artist who found his place and his subjects on the outskirts of the cities he inhabited.

The city of Arles was intimately bound up with the history and uses of the Rhone. As the only waterway connecting the Mediterranean and northern Europe, since antiquity this river had concentrated the traffic of people, goods and cultures, in addition to structuring the lands through which it flowed. In the days before roads and railways, the Rhone was the inland route that linked the cities of Arles (a former imperial town), Avignon (papal seat in the Middle Ages), Valence, Vienne and Lyon to the ports along the French Mediterranean coast. In the early 19th century, with the advent of the Industrial Revolution, the Rhone became the artery connecting the industrial towns along its banks. The creation of the Avignon-Marseille railway line put an abrupt end to the economic prosperity of this riverside city. When Van Gogh painted The Stevedores in Arles, the port has already been reduced to little more than a loading and unloading quay for coal distributors.

This work transports us from the centrality of the city and its rhythms to the suburbs, its outer edges and roads. In the foreground, three people are unloading coal on the bank of the Rhone. Their dark bodies fuse with the blackness of the ore and the shapes backlit by the setting sun. A choreography of harsh, strenuous labour in a silent atmosphere of solemn ordinariness framed by the last ripples of light on the river. In the distance, the impassive city has been reduced to stony blocks with no personality whatsoever. Here, as in our own cities, many production industries and essential jobs were carried out on the edge of town, in the suburbs.

Vincent van Gogh

The Stevedores in Arles, 1888

Oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

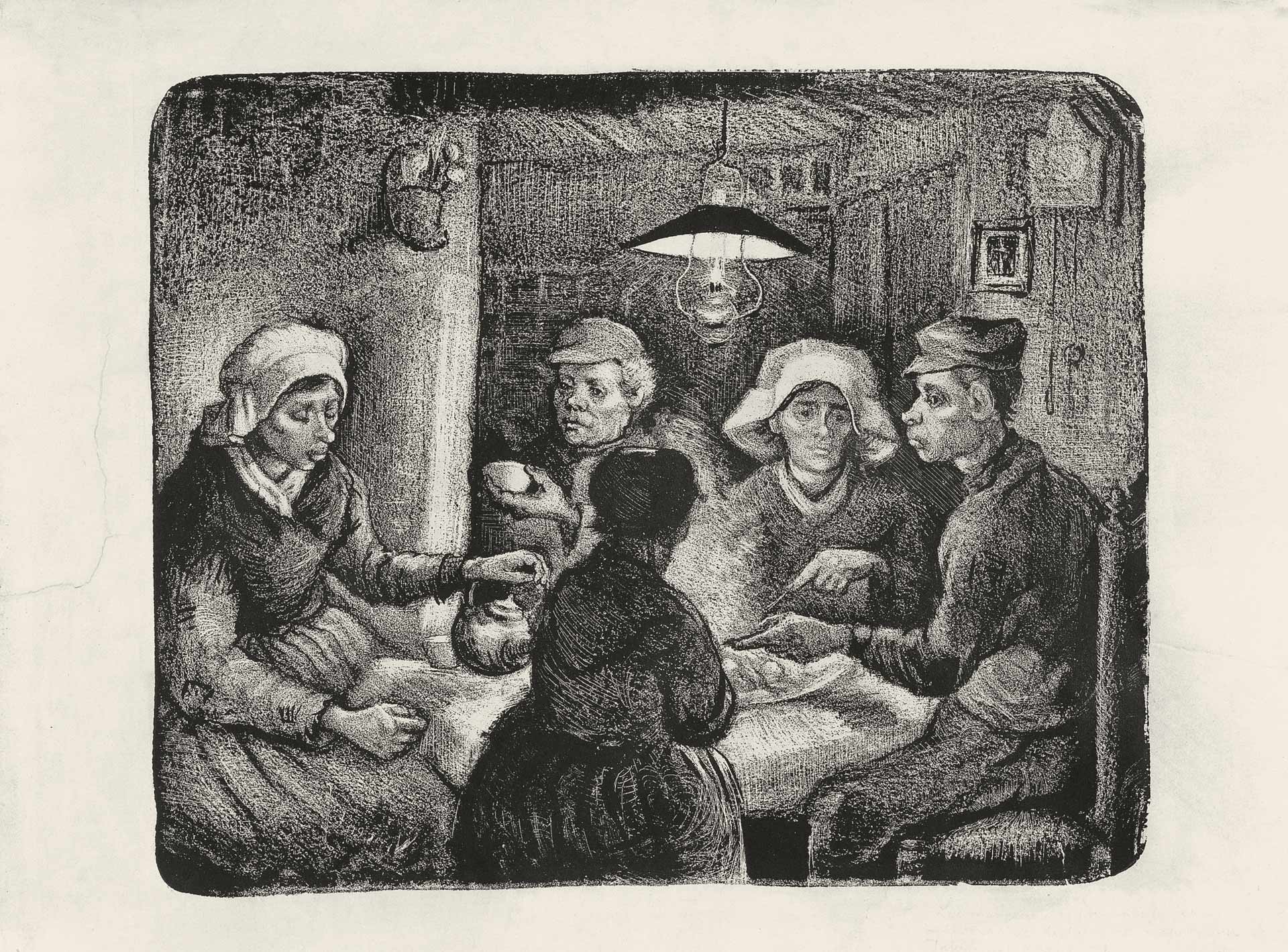

The artist’s interest in depicting the working classes, renewed during his sojourn in Arles, recalls the early Dutch works where Van Gogh portrayed peasants, potato harvesters, weavers and miners. His Potato Eaters series, to which this lithograph belongs, aimed to dignify manual and physical labour, as he explained in a letter: “I have tried to emphasize that those people, eating their potatoes in the lamplight, have dug the earth with those very hands they put in the dish, and so it speaks of manual labor, and how they have honestly earned their food.”

Vincent van Gogh

The Potato Eaters, 1885

Lithograph on Japan paper, 26.5 x 32.5 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

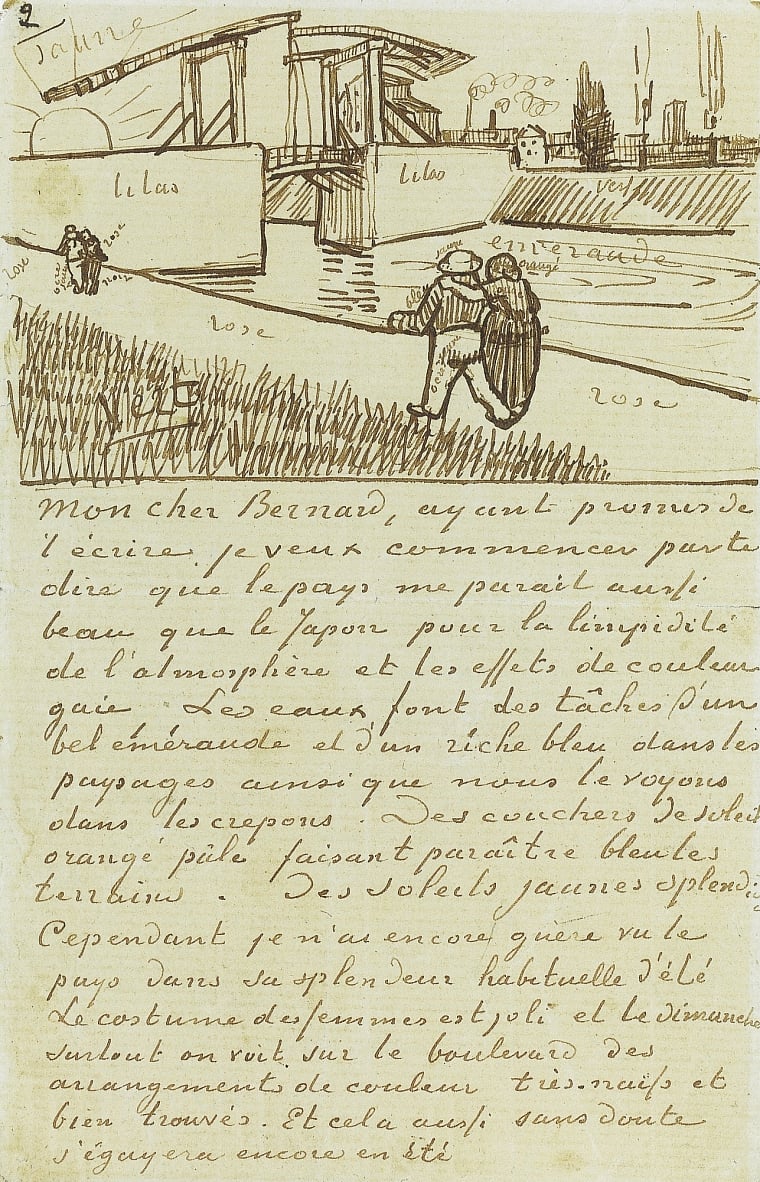

Vincent van Gogh, Letter to Émile Bernard, 1888

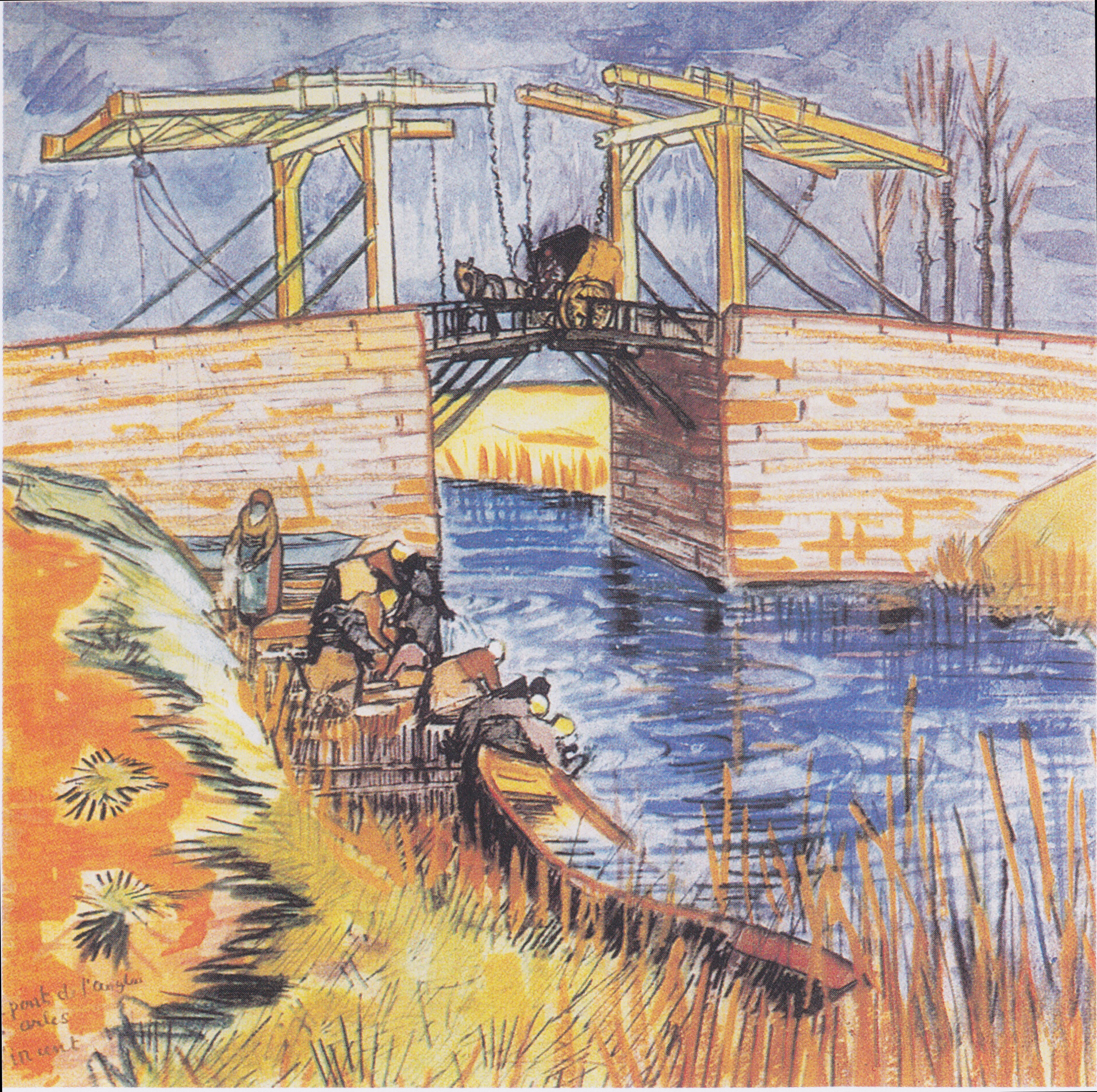

Vincent van Gogh, Bridge at Arles (Pont de Langlois), 1888

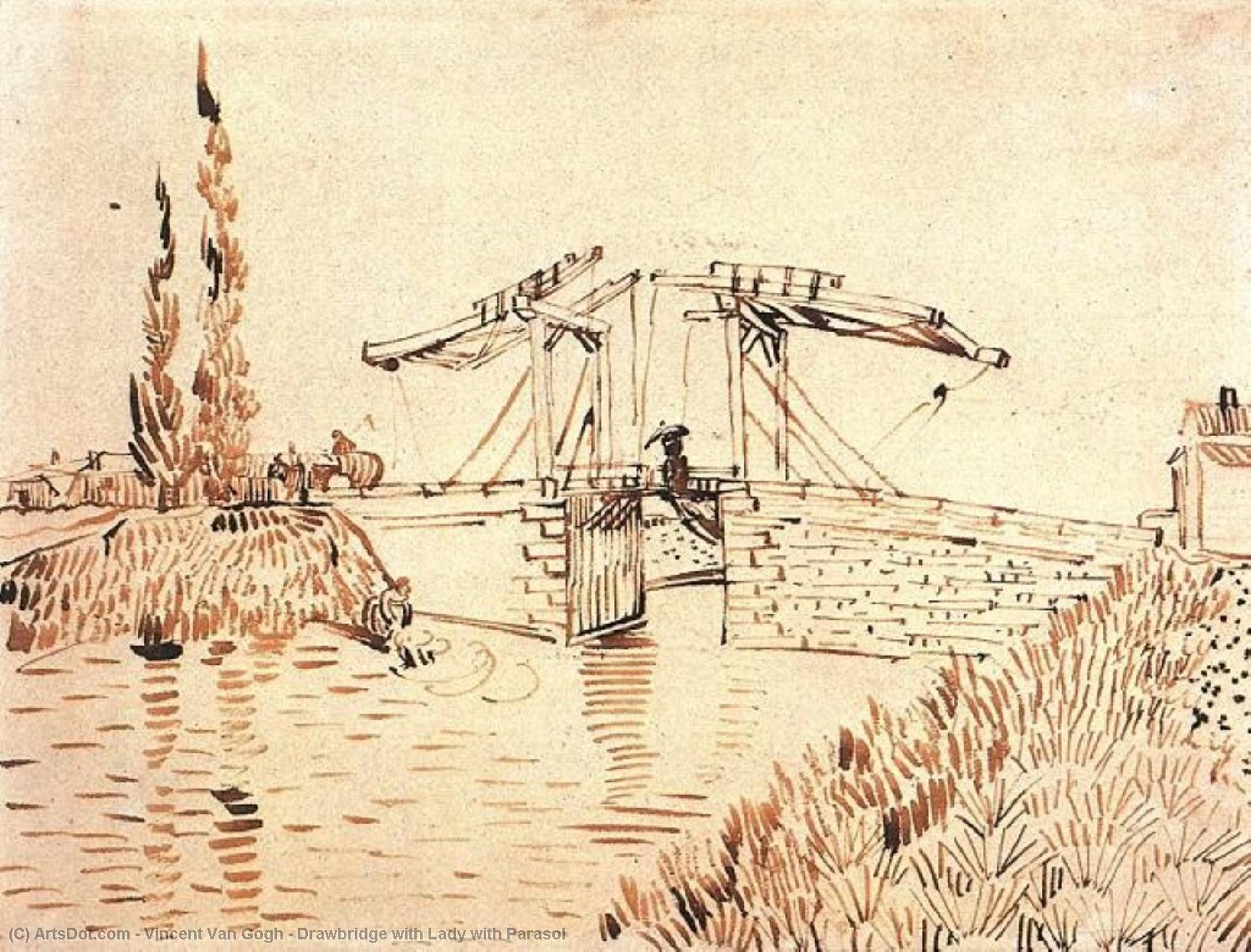

Vincent van Gogh, Drawbridge with Lady with Parasol, 1888

At Arles, Van Gogh was drawn to existence on the periphery, in the transitional spaces between city and non-city. The artist turned his eye to the suburbs and away from the imposing city filled with Roman ruins or medieval monuments. He painted outdoors and hiked along the banks and canals of the Rhone, seeking paths and bridges where life unfolded far from the urban centre. His sketches and drawings captured those outskirts.

One of the places that fascinated the artist was the vicinity of the Langlois Bridge. This drawbridge over a navigable canal near the city was named after one of the men who had guarded it for years. In those days, it was a place of both transit and meeting. Van Gogh visited often and painted it frequently during the summer of 1888. In the mornings, washerwomen would gather on the banks of the canal to wash and dry their laundry, and in the afternoon people liked to stroll there. We can imagine the artist drawing with his reed pen and ink or painting with watercolours, trying various positions around the bridge at different times of day. In 1974, the writer Georges Perec also systematically observed the Place Saint-Sulpice in Paris for three days, with the aim of recording and portraying “what happens when nothing seems to happen”.

On his long walks in search of life outside the urban centre, Van Gogh painted the wetlands of the Camargue, the ghostly Montmajour Abbey rising above the plain of La Crau, and the vast fields around Arles, where he depicted wheat farmers and harvesters hard at work.

Vincent van Gogh, The Langlois Bridge, 1888

In these peripheral spaces, the city is seen at a distance; its codes are diluted and its echoes barely audible. The voices of the fieldworkers and washerwomen and the rhythms of nature are expressed more intensely, and people’s feet do not follow rigid, carefully planned urban patterns. Van Gogh also painted his Starry Nights over the Rhone from there. Upon closer observation, these works seem to tell us that the stars can only be seen clearly from such liminal spaces.

The outskirts of Arles that Van Gogh painted are no longer outskirts today. Time and urban sprawl have absorbed them into the city, giving rise to other outskirts. On this subject, we would do well to remember Georges Perec’s observation in Species of Spaces that, despite what we might think, “suburbs have a strong tendency not to remain as suburbs”.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza