To Paris

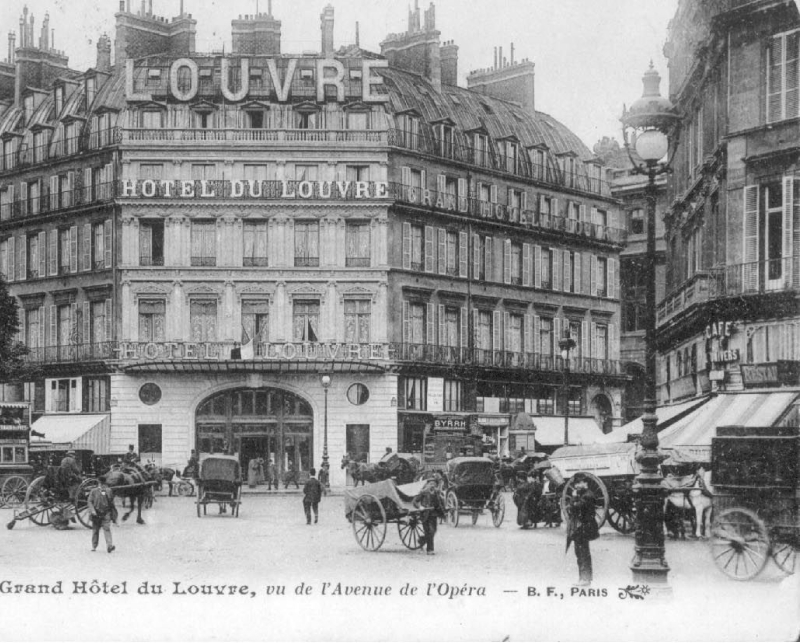

“I forgot to mention that I found a room in the Grand Hôtel du Louvre with a superb view of the Avenue de l’Opéra and the corner of the Place du Palais Royal! It is very beautiful to paint! Perhaps it is not aesthetic, but I am delighted to be able to paint these Paris streets that people have come to call ugly, but which are so silvery, so luminous and vital. They are so different from the boulevards. This is completely modern!” Camille Pissarro to his son Lucien

In January 1898, Camille Pissarro settled into his room at the Grand Hôtel du Louvre (172 rue de Rivoli) to paint Paris. That location offered an incomparable panoramic view of rue Saint-Honoré, Place du Théâtre-Français, avenue de l’Opéra and the lavish Opéra Garnier. From the moment he arrived, the painter fell in love with the vistas and began to create a series of works, one of which was Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain, from 1897.

Camille Pissarro

Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain, 1897

Oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Pissarro first visited Paris in September 1855, when the city was hosting the Exposition Universelle des produits de l’Agriculture, de l’Industrie et des Beaux-Arts. It was the beginning of the Second French Empire, and Napoleon III and Georges-Eugène Haussmann were determined to turn Paris into “the most wonderful city in the world”, even if it meant demolishing nearly 20,000 buildings and ousting thousands of people from their homes.

This radical urban makeover entailed a highly specialised model of land use, property speculation and, consequently, the superiority of certain citizens to others. The new urban layout served the interests of the bourgeois ruling class rather than those of the working classes. The result was a new model of city that imposed a new way of life for its residents; very little remained of the old Paris of narrow streets and tenement communities.

Alfred Guesdon

Palais de l’Industrie, Paris, Exposition Universelle, 1855

Musée Carnavalet

Charles Marville

Urinal with three stalls, boulevard Omano, Paris, 1858–1878

Musée Carnavalet

Charles Marville

Bois de Boulogne, Paris, 1858–1862

Musée Carnavalet

Charles Marville

Rue de Constantine, Paris, circa 1865

Musée Carnavalet

Achille Quinet

Gare du Nord station, Paris, 1870–1880

Musée Carnavalet

If we examine Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain as an urban planning record, it seems as though the Impressionist master wanted to emphasise the frenzied pace of pedestrians, the heavy traffic along that road, and the Haussmannian aesthetic of the street-wall.

He also captured the symmetry and horizontality of the buildings, whose seamless continuity is reinforced by the arrangement of the balconies, windows and cornices: in these five or six-storey structures, the ground floor was used for shops and businesses and the rest for private residences.

In addition, Pissarro copied the position of the fountains and trees in the Place du Théâtre-Français (now Place André Malraux) with almost surgical precision, recalling the fact that Napoleon III and Baron Haussmann had decided to create numerous tree-shaded squares like those of London, with the aim of bringing nature into the urban space.

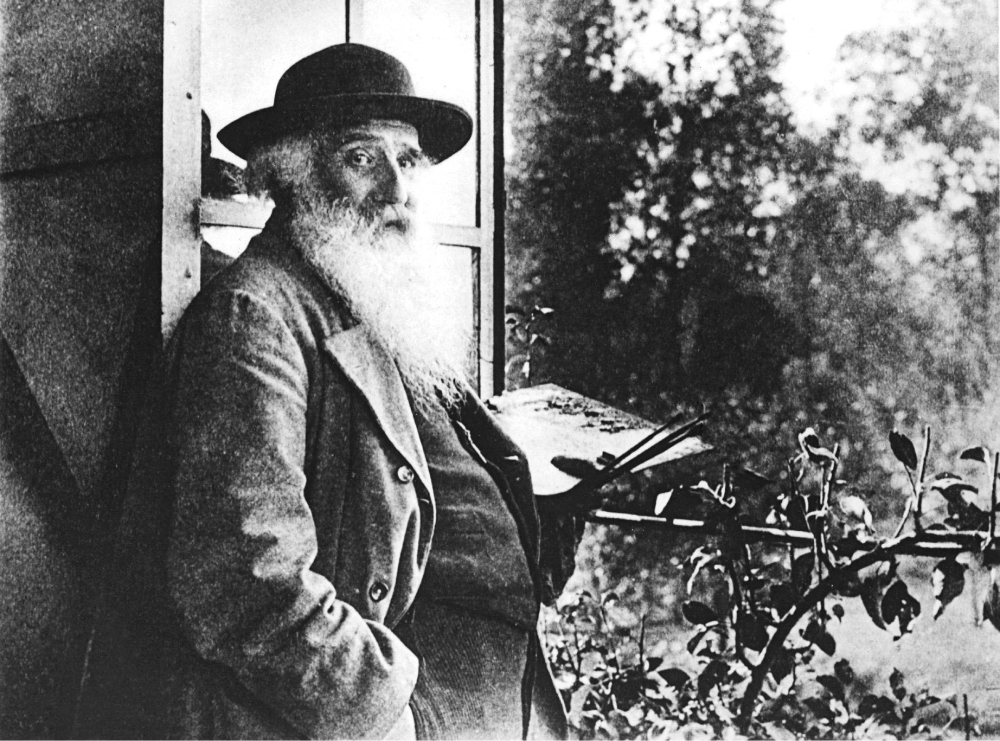

Pissarro at the window of his Éragny studio, palette in hand, circa 1891

Musée Pissarro Archives, Pontoise

Hippolyte Blancard

Rue Saint-Honoré near the Place du Théâtre-Français, Paris, 1888

Musée Carnavalet

Anonymous

Café/restaurant terrace, Paris, 19th–20th century

Musée Carnavalet

Hippolyte Blancard

Fountain of the Place du Théâtre-Français, Paris, circa 1890

Musée Carnavalet

Charles Marville

Lamppost, Louvre courtyard, Paris, 1858–1871

Musée Carnavalet

If we analyse the painting from an ideological perspective, one of the most striking things is Pissarro’s choice of frame, which differs from the more intimate point of view of his rural scenes, underscoring the contrast between pleasant, simple country life and the complex, fast-paced existence of residents in the big city. We should remember that Pissarro’s final works coincided with a growing affinity for anarchist ideas, and that the master mainly resided in small towns like Louveciennes, Pontoise and Éragny.

In his series of cityscapes, the Impressionist may have wanted nothing more than to be an observer: merely contemplate, interacting with no one and going unnoticed. In this way, by renouncing his own wandering, he could make the city, Paris, the true protagonist.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza