To Venice, Amiens

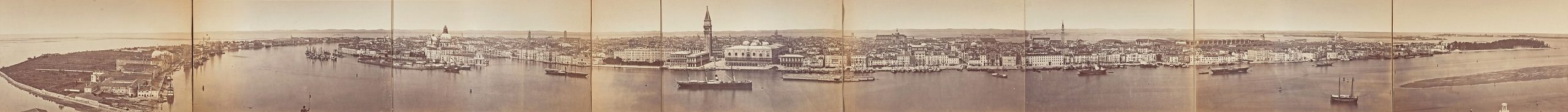

Panorama of Venice, 1870s

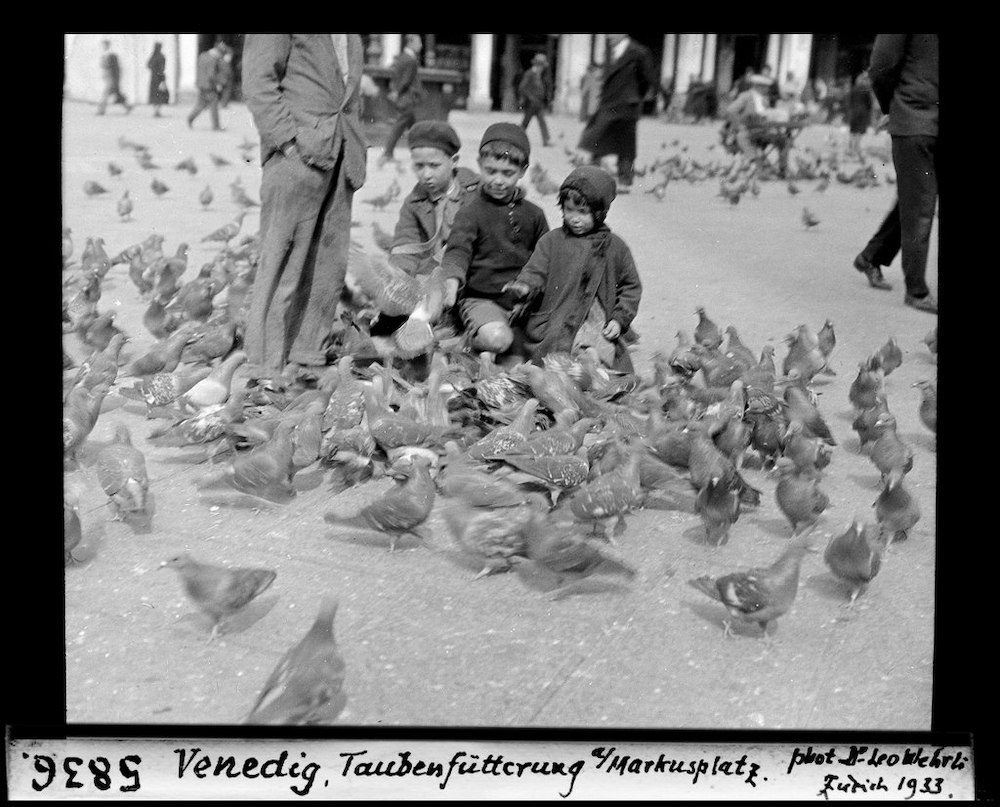

In his book Invisible Cities, Italo Calvino described Maurilia as a place where travellers visit the city and, at the same time, examine old postcards that show it as it used to be, comparing the city of yesterday and today. Venice, like Calvino’s Maurilia, is not only a favourite urban theme of postcards and paintings, but also one of those places where travellers always expect to see the city that once was.

Made up of one hundred and eighteen small islands, the Venetian Lagoon originally offered protection to Roman citizens fleeing from the barbarian invaders. Thanks to its ideal location, Venice eventually developed a prosperous economy based on maritime technology and trade between east and west.

The image and legend of Venice have always gone hand in hand. For a long time, its representation was influenced and inspired by the desire to recreate an idealised city. Vedute or views of Venice were well-known and greatly admired by 18th-century English travellers who visited Italy on their Grand Tour.

Francesco Guardi painted these two panoramic views of Venice in 1780. They show a section of the Grand Canal with San Simeone Piccolo on the right bank and the former church of Santa Lucia, demolished in the 19th century and now a railway station, and church of Santa Maria di Nazareth on the left. The two works complement each other, providing a broader spatial perspective of this part of the city. Many of the depicted buildings have since disappeared, victims of urban transformation, abandonment or military attacks.

Francesco Guardi’s paintings portray a Venice where enduring monumental spaces are combined with the sediment of time and signs of the decline that would lead to its loss of independence in 1806. In Guardi’s works, the people are reduced to tiny abstract brushstrokes, but they walk, talk, work and navigate the canals.

A city is more than just a topographical and urban planning system; it is a complex web of overlapping relationships, emotions and movements. The places we live in are made up of layers, many of them hidden or erased. Where is the history of our cities stored? Are monuments the sole repositories of that legacy? Where are the other, personal memories?

(1)

Francesco Guardi

The Grand Canal with Santa Lucia and Santa Maria di Nazareth, circa 1780

Oil on canvas, 48 x 78 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

(2) Francesco Guardi

The Grand Canal with San Simeone Piccolo and Santa Lucia, circa 1780

Oil on canvas, 48 x 78 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Walter Benjamin compared the city of Paris to an enormous library crossed by the Seine. A great palimpsest of intersecting times and memories, of stories told and others left untold by oblivion or omission. Each inhabitant establishes symbolic marks that define their personal space, that lift part of the city out of anonymity, rendering it intimate and familiar and evoking their sentimental map of the lived space. But where are those impressions stored?

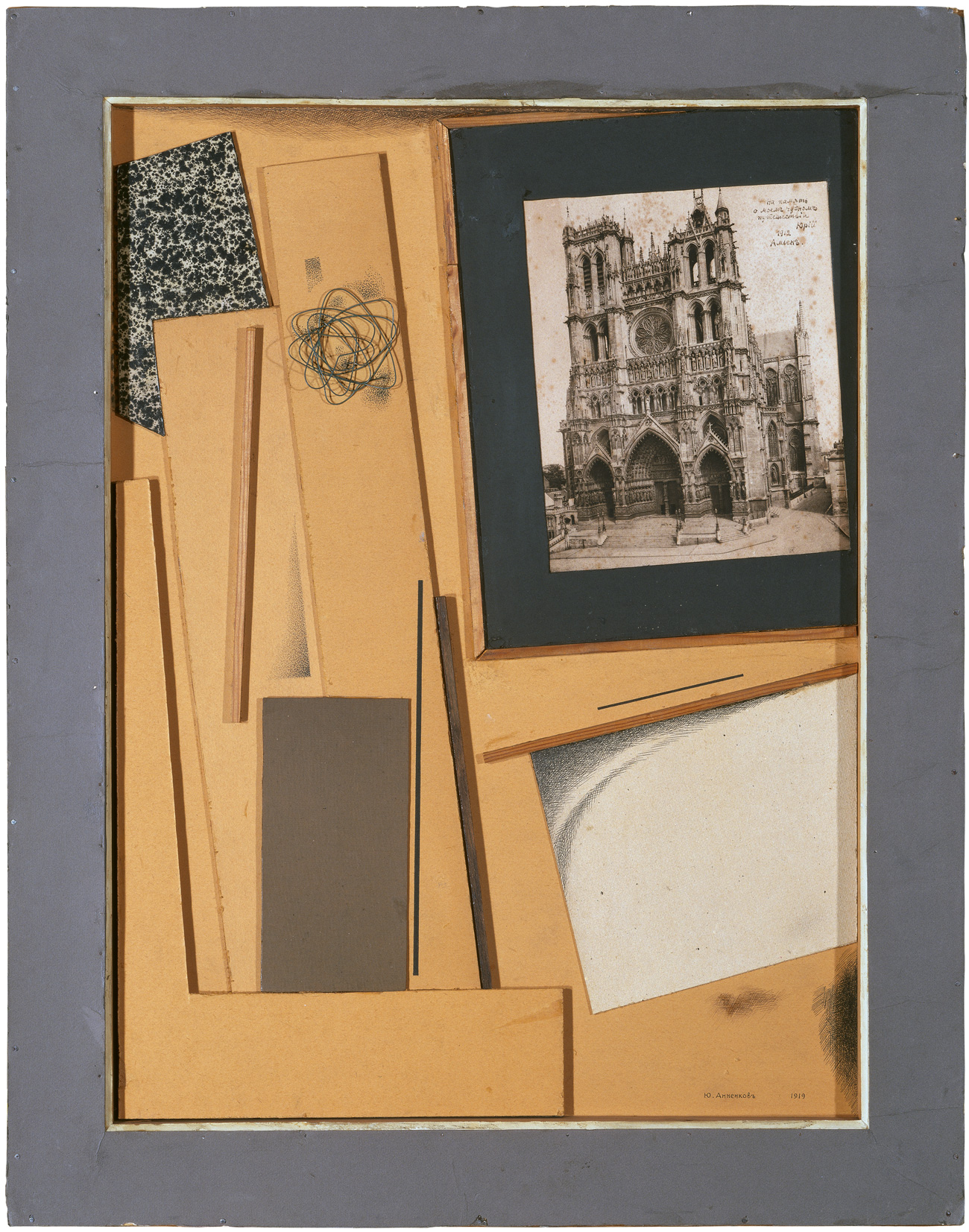

Like many other avant-garde artists, the Russian painter Yurii Annenkov decided to study in Paris, where he stayed in 1911 and 1912. In his second year abroad, he visited other French cities like Amiens, where he bought the postcard included in this work and added a note in Cyrillic script: “Souvenir of my wonderful trip. Yurii, 1912. Amiens.” In 1913, Annenkov returned to Saint Petersburg to continue his artistic career as a set designer and portraitist. He also produced more experimental works like this assemblage from 1919, immortalising his memento of Amiens Cathedral.

Interweaving times and stories around a place leads us to record and visualise narratives that would otherwise be impossible.

Yurii Annenkov

Amiens Cathedral, 1919

Collage, wood, cardboard and wire on paper, 85 x 66.5 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Amiens, 1895

Raoul Berthelé. The square of the Amiens station, 1914-1918

Postcard of rue des Tanneurs, before 1914

Postcard of rue des Trois Cailloux, Amiens

Life in the city of Amiens is symbolically linked to its cathedral, built in the 13th century around the relic of the skull of Saint John the Baptist brought back by Crusaders. For centuries, the saint’s head attracted people affected by deafness, muteness, blindness and, above all, “Saint John’s dance”, as epilepsy was once called. The building had an eventful history. In the 13th century it was struck by lightning and had to be rebuilt, and it came under attack during World War I; in fact, shortly after Annenkov visited and took away that “souvenir of his wonderful trip”, sandbags were heaped around the cathedral to protect it from enemy shells.

Raoul Berthelé, View of Amiens Cathedral protected against bombardment, 1915

In 1915, a chemical engineer, amateur photographer and officer stationed in Amiens named Raoul Berthelé used his camera to document the rear-guard of the Great War. He left us various photographs of life in the city at the time, images that tell stories with first and last names. Like Annenkov’s postcard, each photo is precisely captioned, creating a map of the everyday. The captions tell us where, when and who is pictured in each photograph.

Amiens’s strategic importance as a national railway hub made it a primary target of German forces on the western front. In 1918, a major attack devastated the city. A few months later, when many inhabitants were returning to find their homes in ruins, Yurii Annenkov, caught up in the fervour of revolutionary Russia, recovered his personal memento of that trip to Amiens and used it to create a blend of tradition and innovation, nostalgia and hope for the future.

When we walk through our cities, we are treading on layers of the past, often without knowing it. Beyond the postcards of Maurilia, the Venetian vedute or the photograph framing Annenkov’s personal souvenir, cities are made up of the stories of those who live in them and the memories they leave behind, layer upon layer of human sediment; and every now and then, almost unwittingly, we catch glimpses of ages past and memories lost in those geological strata.

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza