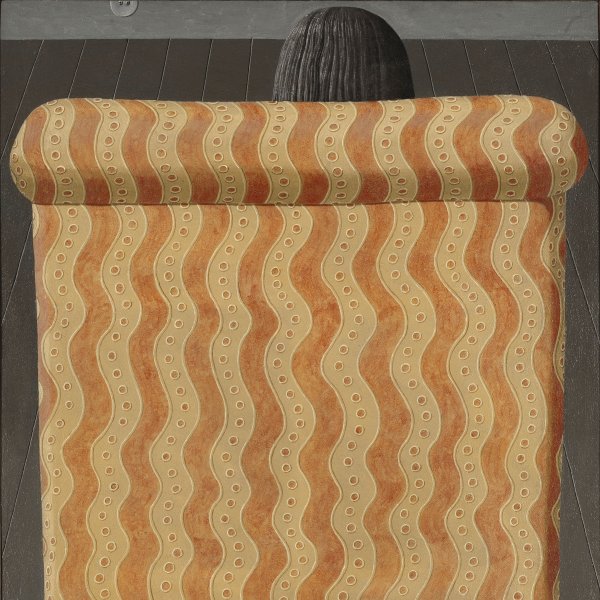

Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror

In this double portrait, George Dyer—for many years Bacon’s lover—sits in a revolving chair facing a mirror placed on a strange piece of furniture with a stand. The violent brutality of the image, with its distorted body and spasm-twisted face, is heightened by a ring of light from a source outside the painting. However, the face reflected in the mirror, though split in two by a strip of light space, is not racked by the same distortions. If the two halves of the reflection were joined together, they would provide a fairly lifelike portrait of Dyer, with his angular profile and hooked nose, and an expression combining a death wish and desire. Building on Picasso’s dislocated portraits of the mid-twentieth century, Bacon succeeds in capturing the most sordid side of human nature.

Firmly rooted in British figurative tradition, the work of Francis Bacon is usually linked to the generically termed School of London, a heterogeneous group of artists — including, apart from Bacon, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff and Michael Andrews, all of whom are represented in the museum collection — who have in common their exaltation of individuality, interest in the human figure, a certain expressionism and distaste for academic naturalism.

In the present Portrait of George Dyer in a Mirror of 1968, the only work by Bacon in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection, the sitter is isolated in an empty space. George Dyer (1934‒1971), an almost illiterate former criminal, who was Bacon’s lover for several years until killing himself with an overdose of drugs in 1971, is seated on a revolving chair opposite his own image reflected in a mirror placed on a strange-looking piece of furniture with a pedestal, a cross between a television set and X-ray machine. The violence and brutality of the image, focused on the distortion of the main figure whose face is contorted by a spasm, as if being subjected to a number of forces from which he cannot break free, is heightened by a circular halo of light from a source located outside the painting. In contrast, the face reflected in the mirror, split into two by a strip of luminous space that appears to be a reflection in the glass, is not distorted as Bacon’s figures usually are; indeed, if the two halves were joined, we would have a fairly naturalistic portrait of Dyer’s face with his craggy profile and hooked nose and an expression that combines desire and death.

Bacon produced highly personal portraits, eliminating all individual physical features and emphasising the unique destiny of each man. The body, as flesh, is the essential element in his portraits, and always holds a double meaning of representation and alienation. The British painter turns his human figures inside out, showing their organs and deforming their faces by means of a distortion that erases their features. With a personal, instinctively created iconography, he sought, in his own words, “to trap a moment of life in its full violence, its full beauty, ” and managed to convey the most sordid and frightening aspects of the human being, and therefore in this respect his painting might be considered a somewhat convulsive interpretation of European existentialism. The deformations of the flesh to which Bacon subjects his figures are also related to the violence of Picasso’s most dislocated figures painted in the mid-twentieth century.

The expressionistic technique employed in the present work is a combination of oil applied with a brush and modelled with the fingers. By brutally splashing thick white brushstrokes over the image, Bacon intentionally breaks with technical conventions and takes risks that are intended to cause unsettling effects. These splashes could be a sort of allegory within the painting whose meaning Bacon leaves unexplained, but also suggest an element of fate of which he wishes to remind us:“My ideal, ” he once stated, “would really be just to pick up a handful of paint and throw it at the canvas and hope that the portrait was there.” Francis Bacon indeed managed to trap that “instant of life” and succeeded like no other artist in translating the most sordid and frightening aspects of the human being. With his existentialist leanings, Bacon is the painter who has best captured on canvas the alienation of today’s man, his vulnerability.

Paloma Alarcó