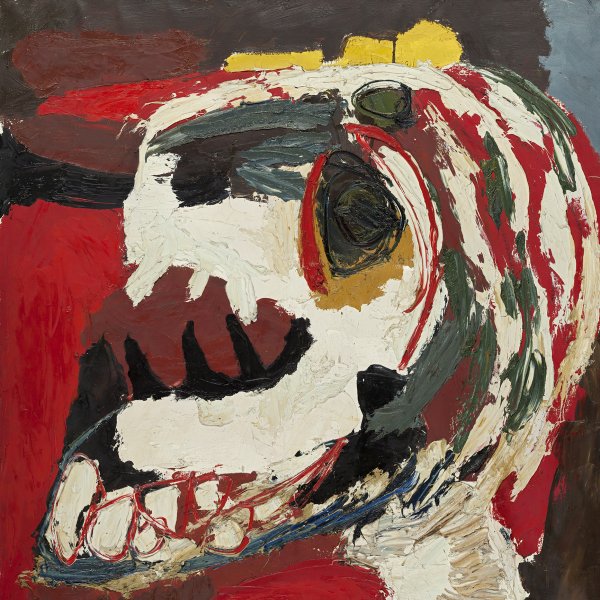

Black Phantom

When the Second World War ended, Willi Baumeister, an artist branded as “degenerate” by the previous regime, became one of the greatest contributors to the rebuilding of the German art scene. His artistic career, which evolved from the earlier Constructivism towards an abstraction that sought to bring to light the primeval, attaching particular importance to the material aspects of painting, can be defined as a perfect synthesis of the two opposing forces in modern art: the rational, intellectualised force derived from Cézanne and Cubism; and the movement linked more to the sphere of fantasy and emotion, which advocates a return to primitive and eternal myths. According to his aesthetic ideas, which were published in 1947 in his essay Das Unbekannte in der Kunst (The Unknown in Art, ) the artist’s chief task was to make visible that which had hitherto inhabited the realm of the unknown: “Art consists precisely in revealing the world to men through the unknown. The nuclear value of art lies in that which is inexplicable, that which is incomprehensible.”

Black Phantom, executed in 1952, belongs to the artist’s final period during which his painting evolved progressively towards planar, abstract and monochrome forms, embodied by the series of Phantoms, Montaru and Monturi. In these works displaying monumental black or white volumes, Baumeister explores the concept of the void, a concept that is always present in his painting. In this case it is an abstract composition based on a biomorphic, weightless, black conglomeration like a phantom floating in space. As in many of the paintings he produced around this time, Baumeister devises a language that imitates materials, making the work a false “painted” collage. The flat surfaces in red, yellow, blue, green and black have ragged edges, as if they had been torn, to create the impression of ripped, and glued paper.

Baumeister was always opposed to the idea of Art Informel as an absolute negation of image, and proposed as an alternative a sort of self-genesis of the vital creative forces. As Michael Semff has pointed out, much of Baumeister’s creation springs from the metamorphosis of the imaginary world. For Willi Baumeister, “the comprehensive power of art in the form of an undying process” lay precisely in this metamorphosis, in this flowering of the unknown.

Paloma Alarcó