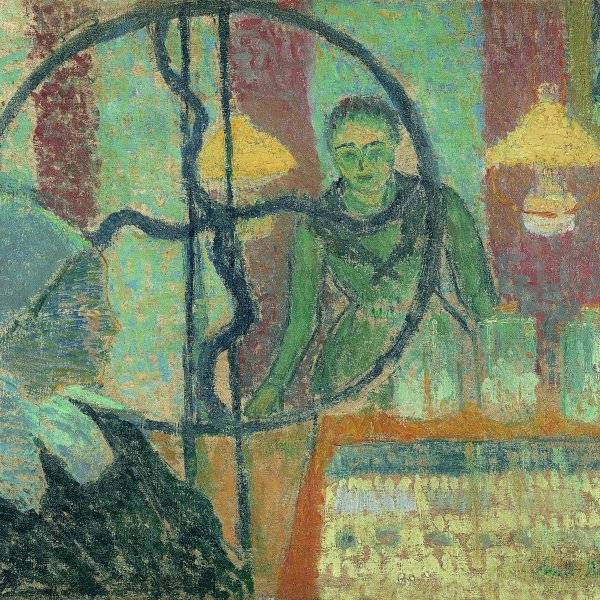

Women Bathing

In 1887, working in collaboration with his friend Louis Anquetin, Émile Bernard created a painting style based on flat colours enclosed within thick simplified outlines, somewhat like the popular images d'Épinal and Japanese prints. The style received the name of cloisonnism, due to its similarity to the appearance of cloisonné (enamel inlaid in sections), whose surface is divided into compartments to prevent the pigments mixing before and during firing.

Anquetin and Bernard's cloisonnism represented a decided break from Impressionism. The Impressionist vision, accentuating reflections of light from certain bodies onto others and the unity of a common atmosphere, tended to dissolve the independence of things. Cloisonnism, on the other hand, isolated objects with a clear, marked outline. This isolation broke away not only from Impressionism but also from the whole tradition of naturalist painting. With the suppression of perspective, shadows and other indications of illusionist space, the composition was reduced to a series of silhouettes outlined against a flat-coloured background. In the summer of 1888 Bernard brought his development of the cloisonnist style to a culmination in a radically innovative painting, Breton Women in the Meadow, which in turn inspired Gauguin to break away from Impressionism in The Vision after the Sermon.

In the present work, far removed from picturesque Breton themes, we still find the essential features of cloissonism and even recollections of Breton Women in the Meadow, with its abrupt changes of scale and the large heads in the foreground. The painting is part of a series of works painted by Bernard in 1889 in connection with a mural (since destroyed) on which the artist was working at the time. One of them was shown in the group exhibition held that year at the Café Volpini and was acquired by the Symbolist poet and critic Albert Aurier. The painting is inspired by the compositions of bathers by Cézanne which Bernard may have seen in Père Tanguy's shop. The whole picture may be considered a subtle commentary on some of Cézanne's teachings: the simplified, geometrical outlines, the proportions of the figures (lengthened in a way that also recalls the work of El Greco, rediscovered at that time), the execution based on parallel vertical brushstrokes that unify the surface of the canvas like a tapestry (Bernard admired Cézanne's "constructive handling"), and the abundant areas of canvas that have been left untouched, barely covered, in the bodies of the bathers.

Guillermo Solana