Tough Customers

1881

Oil on canvas.

76 x 63.5 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.1987.23

)

Not on display

Level 2

Permanent Collection

Level 1

Permanent Collection

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Level -1

Temporary exhibition rooms, Conference room and EducaThyssen workshop

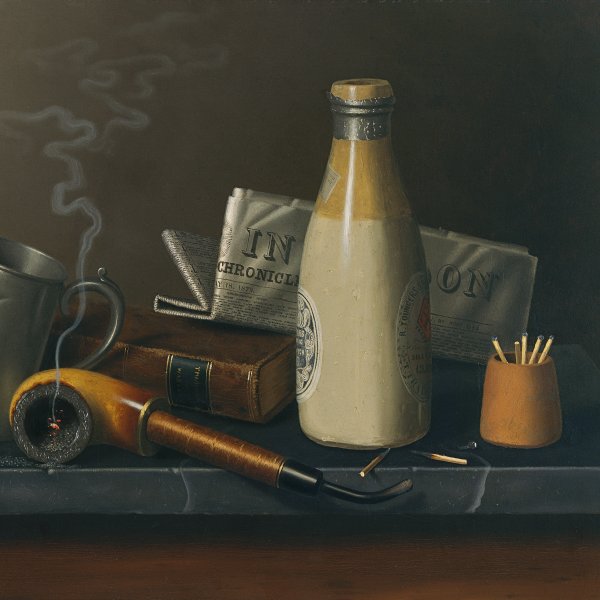

John George Brown has been characterised as the painter of "the children of the poor, the disinherited, the waifs and strays, the orphans", as the artist "who has so successfully caught what one might call the elf-life of New York-that flickering phantasmal humanity of our streets and alleys." As Brown stated to an early biographer, "I want people a hundred years from now to know how the children that I paint looked." The painter, who grew up in poverty in England, was sensitive to his impoverished childhood when he helped to support his mother, brothers and sisters. After he had achieved economic success, the artist proudly acknowledged his beginnings as a working man, stating that I do not paint street urchins "solely because the public likes such pictures and pays me for them, but because I love the boys myself, for I, too, was once a poor lad like them."

At the time Brown painted Tough Customers, homeless youths, their faces "preternaturally aged, brutalised, and defrauded of all that belongs to childhood" numbered by the tens of thousands in New York City. Some were the product of a rapidly growing urban society swelled by an influx of immigrants, some were abandoned by dissolute parents, others were orphaned by the Civil War, while still others resulted from the rural poor migrating to the cities. Young girls were numerous among the street vendors selling matches, toothpicks, cigars, newspapers, songs, and flowers. "The flower-girls are hideous little creatures", noted a contemporary observer, "but their wares are beautiful and command a ready sale." The trade of these flower-merchants was not limited to the selling of flowers, but was often a "cover for any number of pursuits, from setting up for pickpockets to child prostitution." Compared with the graphic contemporary photographs by Jacob Riis or Lewis Hine or the sardonic street children in the canvases by David Gilmour Blythe, the waifs in Brown's paintings are remarkably healthy, well-scrubbed, and resoundingly cheerful.

The title of Brown's painting is ironic. The "Street Arabs", as the homeless children in New York were called, surround the flower seller wearing her button hole bouquets which would sell for ten cents. As the critic, S. G. W. Benjamin, described the painting in 1882, the group "represents a little flower-girl, besieged by the admiring but penniless ragamuffins, who are endeavouring by a little blarney to win the roses they cannot afford to buy." There is an obvious rapport between the girl and her "tough customers." The young flower seller wears a knit wool hat, cotton dress torn at the elbow, white cotton knit socks and black leather boots. Only the gold ring, which is too large for her and she wears on her middle finger, calls into question a legitimate ownership and suggests the unsavoury conditions of street life. The same young model also appears in Brown's Buy a Posy, c. 1881, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. The isolated flower seller, wearing the identical knit hat and stockings, but in different dress, is now selling larger bouquets as she plaintively looks for a customer. Martha J. Hoppin has noted that the girl wears worn, but decent clothes, as often the models that Brown carefully recruited from the streets would be cleaned up and scrubbed by their benefactors when presented to the artist in his studio. Brown's greatest problem would be to get his sullen-faced models to smile -"for to paint a smile is one of the difficulties of figure-painting- a successful smile, I mean; a smile that will make the spectator smile."

It was this positive quality of Brown's painting, which stressed smiling youthful entrepreneurs, often bootblacks, that appealed to his audience. The cohesive bonding of the male youths, recipients of the largess of the flower seller in Tough Customers, could be seen by the wealthy patrons of Brown's paintings as reflective of the male rapport of their own social strata. In the 19th century the street vendors, newspaper sellers, and bootblacks were seen as independent merchants, working for profit rather than wages. The activities of the waifs of the streets in Brown's canvases suggest a rags-to-riches Horatio Alger scenario that the artist himself experienced.

Kenneth W. Maddox

At the time Brown painted Tough Customers, homeless youths, their faces "preternaturally aged, brutalised, and defrauded of all that belongs to childhood" numbered by the tens of thousands in New York City. Some were the product of a rapidly growing urban society swelled by an influx of immigrants, some were abandoned by dissolute parents, others were orphaned by the Civil War, while still others resulted from the rural poor migrating to the cities. Young girls were numerous among the street vendors selling matches, toothpicks, cigars, newspapers, songs, and flowers. "The flower-girls are hideous little creatures", noted a contemporary observer, "but their wares are beautiful and command a ready sale." The trade of these flower-merchants was not limited to the selling of flowers, but was often a "cover for any number of pursuits, from setting up for pickpockets to child prostitution." Compared with the graphic contemporary photographs by Jacob Riis or Lewis Hine or the sardonic street children in the canvases by David Gilmour Blythe, the waifs in Brown's paintings are remarkably healthy, well-scrubbed, and resoundingly cheerful.

The title of Brown's painting is ironic. The "Street Arabs", as the homeless children in New York were called, surround the flower seller wearing her button hole bouquets which would sell for ten cents. As the critic, S. G. W. Benjamin, described the painting in 1882, the group "represents a little flower-girl, besieged by the admiring but penniless ragamuffins, who are endeavouring by a little blarney to win the roses they cannot afford to buy." There is an obvious rapport between the girl and her "tough customers." The young flower seller wears a knit wool hat, cotton dress torn at the elbow, white cotton knit socks and black leather boots. Only the gold ring, which is too large for her and she wears on her middle finger, calls into question a legitimate ownership and suggests the unsavoury conditions of street life. The same young model also appears in Brown's Buy a Posy, c. 1881, North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh. The isolated flower seller, wearing the identical knit hat and stockings, but in different dress, is now selling larger bouquets as she plaintively looks for a customer. Martha J. Hoppin has noted that the girl wears worn, but decent clothes, as often the models that Brown carefully recruited from the streets would be cleaned up and scrubbed by their benefactors when presented to the artist in his studio. Brown's greatest problem would be to get his sullen-faced models to smile -"for to paint a smile is one of the difficulties of figure-painting- a successful smile, I mean; a smile that will make the spectator smile."

It was this positive quality of Brown's painting, which stressed smiling youthful entrepreneurs, often bootblacks, that appealed to his audience. The cohesive bonding of the male youths, recipients of the largess of the flower seller in Tough Customers, could be seen by the wealthy patrons of Brown's paintings as reflective of the male rapport of their own social strata. In the 19th century the street vendors, newspaper sellers, and bootblacks were seen as independent merchants, working for profit rather than wages. The activities of the waifs of the streets in Brown's canvases suggest a rags-to-riches Horatio Alger scenario that the artist himself experienced.

Kenneth W. Maddox