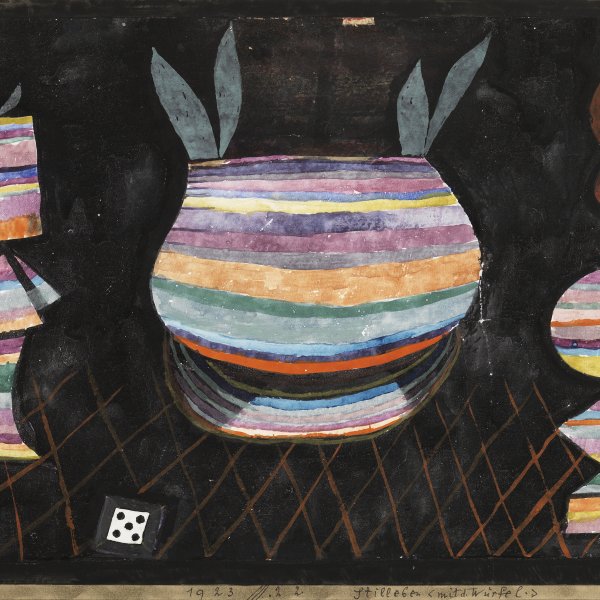

Construction in Space-Time II

1924

Gouache, pencil and ink on Tracing paper.

47 x 40.5 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

527

(1978.68

)

Not on display

Level 2

Permanent Collection

Level 1

Permanent Collection

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Level -1

Temporary exhibition rooms, Conference room and EducaThyssen workshop

Theo van Doesburg developed a greater interest in architecture in the early 1920s and even abandoned painting for a time in order to devote himself to investigating architectural and spatial problems.

In 1920 and 1921 he worked for the architect Cornelis de Boer in Drachten and shortly afterwards settled in Weimar, where, despite having been excluded from the teaching staff of the Bauhaus by

Gropius, he taught a course to the students of the school at his studio. It was then that he met the Dutch architect Cornelis van Eesteren, with whom he collaborated on a series of projects that were shown at the Galerie L’Effort Moderne in Paris in 1923. The models and axonometric projections he and Van Eesteren made for the exhibition, in which they studied the distinction between the two-dimensionality of painting and the three-dimensionality of architecture, and his own architectural constructions in primary colours, in which the interior and exterior were interrelated, are reflected in the Construction in Space-Time II belonging to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza. Indeed, the work is part of a set of preparatory drawings for the design of the house-cum-studio he and his wife Nelly planned to share with Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber at Meudon Val Fleury, near Paris. For reasons that are unknown, the project was never finished.

Nor can there be any doubt that these axonometric projections may be considered Van Doesburg’s response to the influence of El Lissitzky, whom he had met slightly earlier in Berlin. These international contacts prompted Van Doesburg to reconsider the rigid initial ideas of De Stijl, leading to a more dynamic conception of his deconstructions and a new manifesto which he was to call “Elementalism.”

Paloma Alarcó

Nor can there be any doubt that these axonometric projections may be considered Van Doesburg’s response to the influence of El Lissitzky, whom he had met slightly earlier in Berlin. These international contacts prompted Van Doesburg to reconsider the rigid initial ideas of De Stijl, leading to a more dynamic conception of his deconstructions and a new manifesto which he was to call “Elementalism.”

Paloma Alarcó