“My work is like my behaviour — not harmonious in the sense of classical composers, not even in the sense of the classical revolutionaries. Subversive, uneven and contradictory, to the specialists in art, culture, manners, logic, morals it is unacceptable.” This quotation by Ernst, published by Werner Spies, shows his rejection of artistic norms and attests to the changing nature of his work, which fluctuates between aggressiveness and exaltation.

During the Second World War Max Ernst’s eventful life became the perfect plot for a novel. In 1938, after leaving the Surrealist group out of solidarity with Paul Éluard, he went to live with Leonora Carrington in Saint-Martin d’Ardèche, where the couple restored a house together, filling it with reliefs and paintings. His peaceful, creative retreat was interrupted by the outbreak of war when he was imprisoned on account of his German nationality. Following several attempts at escaping and his eventual release thanks to Paul Éluard’s intervention, he returned to Saint-Martin only to find himself alone, as Leonora, suffering from deep depression, had been committed to a psychiatric hospital in Spain. With Europe at war and France occupied, Ernst, like other European artists and intellectuals, decided to emigrate to the United States. After overcoming all kinds of difficulties, in July 1941 he arrived in New York, where he married the collector Peggy Guggenheim soon afterwards.

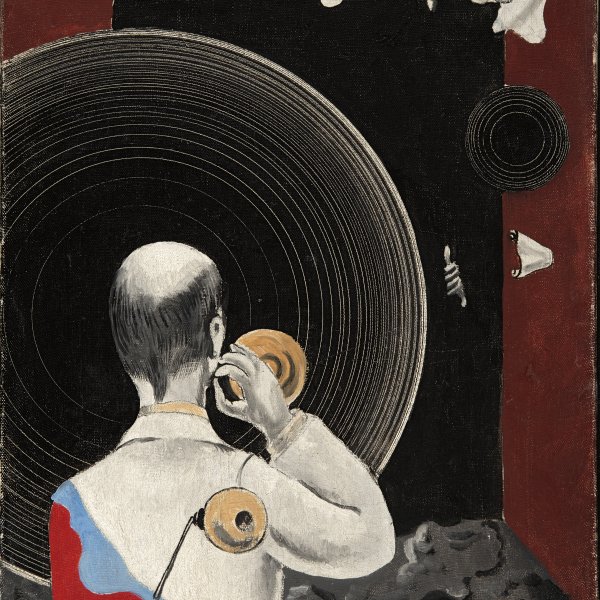

Solitary and Conjugal Trees was executed before the artist departed for America, at a time when a new direction is evident in his work. The devastated cities he had painted during the mid-1930s had given way to phantasmagorical landscapes populated by anthropomorphic figures, such as the apocalyptic Europe after the Rain, which he completed in the United States. These landscapes had been executed using decalcomania, a semi-automatic technique based on the random distribution of colours applied haphazardly, first to glass or some other smooth surface, which was then pressed against the canvas. It had been employed by Victor Hugo, a great forerunner of the Surrealists, and taken up again by Óscar Domínguez in his gouaches of 1935, and was applied by Max Ernst in his oil paintings of the late 1930s.

These imposing Trees resembling compact cypresses with a porous quality that at times recalls marble or volcanic formations, or perhaps even the stalagmites Ernst may have seen at Aven d’Orgnac, a grotto near Saint-Martin d’Ardèche, are painted using the same technique. Certain images can be made out amid the petrified forms infused with a complex symbolism, such as a female nude being preyed on by a menacing bird, a horse’s head and several faces in profile. Ernst provides a double vision — paradisiacal and apocalyptic — of the world and achieves the “convulsive beauty” of which Breton speaks in his writings and which recalls the painting of Gustave Moreau or Arnold Böcklin, but also images from romantic literature.

Christopher Green connects this painting with Leonora Carrington’s novel Little Francis, written in 1937, especially the passage that tells how little Francis (Leonora) and his aunt Ubriaco (Ernst) arrive in Saint-Roc (Saint-Martin): “They sat where they could see the river and the tall calcareous cliffs opposite. The rocks were shaped after a hundred different creatures. / ‘I used to know a man who passed his whole life making the landscape into a zoo’, said Uncle Ubriaco dreamily. ‘He worked for years making rocks into lions and tigers, cabinet ministers, centaurs, historical characters, etc. He was a charming fellow, but worked too hard. I think cypress trees are delightful, they remind me of wigs, and as they usually grow in cemetries one imagines some beautiful lady’s death’s head underneath.’”

Paloma Alarcó

Search

Ir al contenido principal

Search

Ir al contenido principal