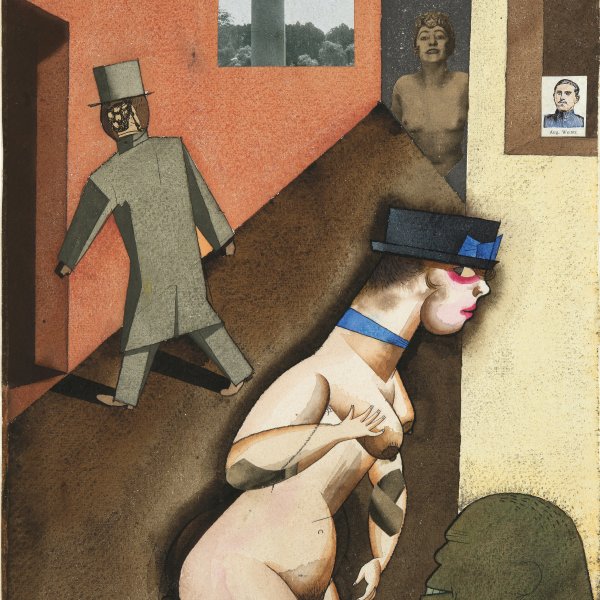

Street Scene (Kurfürstendamm)

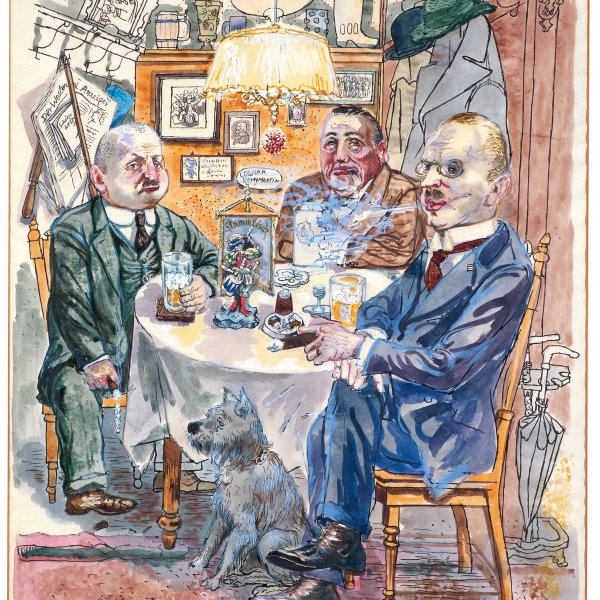

Halfway through the 1920s George Grosz’s gradual evolution towards more realist forms brought him close to Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), the movement springing from the legendary programmatic exhibition by the same name, which was organized by the active director of the Kunsthalle Mannheim, Gustav Hartlaub, and defined a whole era. The show, which brought together a heterogeneous group of German artists with a common interest in breaking with Expressionism through a new objective figuration, was in keeping with the widespread tendency of a return to order in Europe of the 1920s, but unlike in other countries, in Germany it manifested itself as a spirit of fierce social denunciation.

For Germany, the war had resulted in a toll of five million dead and a million mutilated, and affected the vast majority of German society. Following the military defeat and abdication of Wilhelm II, Berlin continued to be the capital of the newly created Republic established by the Weimar constitution of 1920.Whereas during the early days of the Great War the streets of Berlin had filled with young people extolling the virtues of war, which they viewed as a purifying sacrifice, four years later it was a very different sight. The German capital became a place of political struggle, street skirmishes and social unrest triggered by poverty and soaring inflation.

It is only logical that these years of political and moral revolution, great frustrations and great hopes should have kindled a heightened critical spirit and a new conception of art as a political weapon. Like many of his contemporaries, George Grosz translated the internal breakdown of German society into art with biting sarcasm and, like Daumier and Hogarth before him, created a sort of mercilessly enacted human comedy. The modern metropolis became a recurring theme in his work and, in the manner of a modern Bosch with a mordant critical tone and keen sense of observation, he depicted the surrounding environment with a moralising intention in order to show the hypocrisy of bourgeois life and the depravity concealed behind its outward appearance of respectability.

The present Street Scene, dated February 1925, is a good example of Grosz’s new objective painting and of his permanent rebellion against the unjust social order and the hypocrisy and vulgarity of the urban middle class. This depiction of the centrally-located Kurfürstendamm in Berlin, in which the glamour of the wealthy classes contrasts with the poverty of the homeless, immigrants and numerous war cripples, recalls the description given by Alfred Döblin in Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929), which tells the story of Franz Biberkopf, an ordinary citizen who tries to make his way in a society dominated by unemployment, violence and unfulfilled promises; and also that of the plays of Bertolt Brecht, with their lurid images of modern life, of the “dull lives” of those who attempt to wade through the “jungle of cities.”

The work remained in the artist’s possession until 1938, when it was acquired by Erich Cohn, a German who had sought refuge in America and one of the first collectors to purchase works by Grosz after the artist fled Germany in 1933. Years later it passed to the Munich collector Hans Grote, whose collection, including important works by Grosz, Beckmann, Kirchner and Müller, was sold by the Galerie Thomas in Munich in 1981 with the fictitious name of “Sammlung Rheingarten.” It was then that Street Scene was acquired by Baron Thyssen-Bornemisza.

Paloma Alarcó