Caffè Greco

After secretly belonging to the Italian Communist Party in the period when Mussolini was in power, during which he also opposed the neoclassicism advocated by the Fascists, Renato Guttuso became a key figure in the debate that emerged in post-war Italy between the politically engaged neo-realism encouraged by the Fronte nuovo delle arti and abstraction. His oeuvre gradually became influenced both by the new Art Informel trends and by the work of the Pop artists, which he saw for himself at the Venice Biennale of 1964. Furthermore, for a time he indentified with the existentialism of Giacometti and admired the new figuration of Francis Bacon and Gerhard Richter. The Italian painter was always attracted by large compositions illustrating revolutions, disasters or social themes, such as his Execution by Firing Squad in the Countryside of 1938, which is related to the execution of the poet Federico García Lorca by the Falangists during the Spanish Civil War, and La notte di Gibellina of 1970, a work capturing the effects of the earthquake that devastated Messina in 1970.

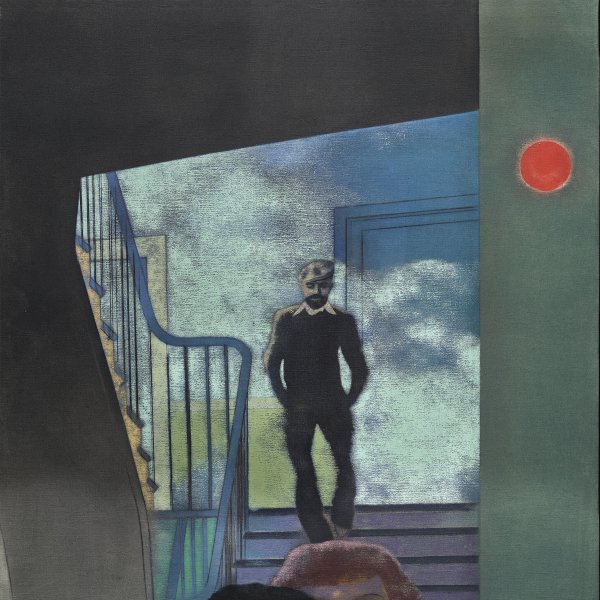

In the mid-1960s, from his Autobiography cycle of 1966 onwards, memory began to play an essential role in Guttuso’s output. After moving into his new residence on the famous via Margutta in Rome, the painter started to incorporate into his works memories of his Sicilian childhood and life in Rome, which he recomposed and reworked with his own imagination, in some cases stripping them of any trace of veracity. These experiments, in which the restrictions of unity of time and place disappear, are executed with a narrative objectivity that pursues the immediacy of an unrepeatable instant and are close in spirit to the Pop trends and the so-called New Figuration. They continue in two large compositions from the 1970s representing fictional narratives: Funeral Banquet with Picasso, dated 1973, a tribute to Picasso, and Caffè Greco of 1976, dedicated to Giorgio de Chirico.

Caffè Greco belonging to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza collection is a huge cartoon for a larger work on canvas housed in Cologne. It shows the interior of this old café, which after opening in 1760 on Rome’s legendary via Condotti became the favourite meeting place of Roman society and of numerous writers and artists visiting the city, such as Keats, Goethe, Stendhal and Baudelaire. The scene depicted, which takes place in the so-called sala rossa, named after the red damask that lines its walls adorned with paintings, sculptures and various mirrors, conceals a sort of allegorical banquet, an impossible fable in which people are intertwined through time. Artists from all periods are shown, combined anachronistically with several Japanese tourists and a varied selection of people from his own day. “He wanted to give — even if only through a sign — the feeling of the café’s history; and so, while the characters are those of today — intellectuals, Swedish girls, the Japanese with the camera, ambiguous lesbian couples, I have sought to introduce a single link with its history, precisely Colonel William Cody, known as Buffalo Bill, who frequented the café when he was in Rome with his equestrian circus.”

The profile figure of Giorgio de Chirico, an artist whom Guttuso regarded as the last survivor among the great geniuses of the century, is shown seated on the left, gazing at the rest of the people. According to the artist, his presence acted as a “catalyst” of the scene, although he went on to explain that “the fascination with the place largely stemmed from the people who had passed through it, from Buffalo Bill to Gabriele d’Annunzio.”

Paloma Alarcó