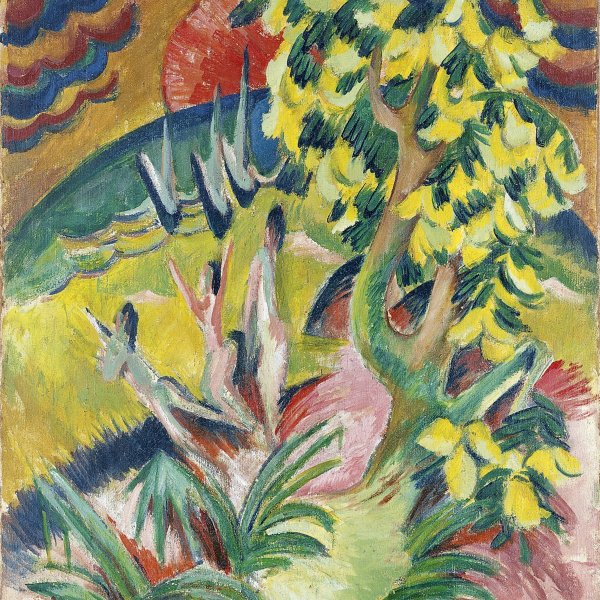

Street with Red Streetwalker

1914 - 1925

Oil on canvas.

125 x 90.5 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

614

(1973.63

)

ROOM 37

Level 1

Permanent Collection

In autumn 1911, Kirchner, like the rest of the members of Die Brücke, moved from Dresden to Berlin in pursuit of new stimuli. Since 1908 what was then the capital of the empire had been home to Otto Müller, a member of the group from 1910, and Max Pechstein, who had settled there after returning from Italy in 1908.

The world of the seething metropolis fascinated Kirchner and his painting underwent a transformation in both subject matter and style. During the months leading up to the Great War, following the breakup of the Die Brücke group in 1913 — “one of the most solitary periods of my life, ” as he himself described it — Kirchner painted numerous Strassenszenen, street scenes which earned him deserved recognition as an Expressionist painter of the city. It was around that time that the writings of the sociologist George Simmel on the dehumanisation of city life, which were echoed in artists like Kirchner and writers such as his friend Alfred Döblin, the author of Berlin Alexanderplatz, were beginning to be disseminated. The artist wandered around the capital making quick sketches of the hasty passers-by and the many social outcasts who lived in old Berlin. He was particularly fascinated by circus artistes, cabaret dancers and prostitutes, whose existence on the fringes of society belonged, in Nietzschian terms, to the same world as the visual arts.

According to the inscription on the reverse, Strasse mit roter Kokotte was painted in Berlin in 1914. The central part of the composition is dominated by the figure of the whore dressed strikingly in red, turned into a symbol that is both bourgeois and anti-bourgeois. Standing at a street corner, she attracts the attention of several male passers-by depicted in the same scene. A postcard Kirchner sent Heckel on 4 April 1910 displays a very similar composition: a woman strolling by dressed in red, with a prominent diagonal that marks the passage of several male passers-by and an outlined figure in the foreground. This shows that while in Berlin Kirchner developed a number of artistic ideas that he had already touched on in his previous period.

The composition displays a geometric arrangement that structures the entire picture surface in an ordered manner and is painted in the angular, deformed style characteristic of the artist’s Berlin period, with an unstable space constructed by prominent diagonals that recall Munch and the formal schematisation of Cubism. The isolation of the figures, which, as Dube points out, is due to the fact that the artist wishes to convey “the hectic and unnatural condition of the modern metropolis, ” is combined with an Expressionist spontaneity taken to an unprecedented intensity.

Years later, on 30 September 1925, the artist wrote in his diary at Davos that he had covered over the fast, nervous brushstrokes characteristic of the Berlin period of 1913 and 1914 with new, broad and flat layers more in accordance with his final style. There is a pastel painting very similar to the present work in Stuttgart — although much more explicitly erotic — which was described by Ketterer as “clearly the greatest of all [Kirchner’s] street scenes of prostitutes.” The nervous brushstrokes of the Stuttgart pastel give an idea of what the present painting must have looked like before it was later retouched by the artist.

According to Donald Gordon, the work passed directly from the artist’s Estate to the collection of Dr Ferdinand Ziersch and his family and to the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection. However, as Peter Vergo pointed out, in the correspondence between Kirchner and the dealer Ferdinand Möller of February and March 1929, his friend asked him for two paintings from before the war: Street with Red Streetwalker and Russian Dancer. Kirchner enclosed in his reply to Möller photos of the aforementioned works for him “to show to those interested.” On 30 March 1929 Möller wrote to Kirchner enquiring about the possibility of sending him the paintings so that they could be viewed by the collector Hermann Lange of Krefeld, who had shown an interest in purchasing them. However, it has not been possible to ascertain whether the painting was eventually sold or returned to the artist.

Paloma Alarcó

The world of the seething metropolis fascinated Kirchner and his painting underwent a transformation in both subject matter and style. During the months leading up to the Great War, following the breakup of the Die Brücke group in 1913 — “one of the most solitary periods of my life, ” as he himself described it — Kirchner painted numerous Strassenszenen, street scenes which earned him deserved recognition as an Expressionist painter of the city. It was around that time that the writings of the sociologist George Simmel on the dehumanisation of city life, which were echoed in artists like Kirchner and writers such as his friend Alfred Döblin, the author of Berlin Alexanderplatz, were beginning to be disseminated. The artist wandered around the capital making quick sketches of the hasty passers-by and the many social outcasts who lived in old Berlin. He was particularly fascinated by circus artistes, cabaret dancers and prostitutes, whose existence on the fringes of society belonged, in Nietzschian terms, to the same world as the visual arts.

According to the inscription on the reverse, Strasse mit roter Kokotte was painted in Berlin in 1914. The central part of the composition is dominated by the figure of the whore dressed strikingly in red, turned into a symbol that is both bourgeois and anti-bourgeois. Standing at a street corner, she attracts the attention of several male passers-by depicted in the same scene. A postcard Kirchner sent Heckel on 4 April 1910 displays a very similar composition: a woman strolling by dressed in red, with a prominent diagonal that marks the passage of several male passers-by and an outlined figure in the foreground. This shows that while in Berlin Kirchner developed a number of artistic ideas that he had already touched on in his previous period.

The composition displays a geometric arrangement that structures the entire picture surface in an ordered manner and is painted in the angular, deformed style characteristic of the artist’s Berlin period, with an unstable space constructed by prominent diagonals that recall Munch and the formal schematisation of Cubism. The isolation of the figures, which, as Dube points out, is due to the fact that the artist wishes to convey “the hectic and unnatural condition of the modern metropolis, ” is combined with an Expressionist spontaneity taken to an unprecedented intensity.

Years later, on 30 September 1925, the artist wrote in his diary at Davos that he had covered over the fast, nervous brushstrokes characteristic of the Berlin period of 1913 and 1914 with new, broad and flat layers more in accordance with his final style. There is a pastel painting very similar to the present work in Stuttgart — although much more explicitly erotic — which was described by Ketterer as “clearly the greatest of all [Kirchner’s] street scenes of prostitutes.” The nervous brushstrokes of the Stuttgart pastel give an idea of what the present painting must have looked like before it was later retouched by the artist.

According to Donald Gordon, the work passed directly from the artist’s Estate to the collection of Dr Ferdinand Ziersch and his family and to the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection. However, as Peter Vergo pointed out, in the correspondence between Kirchner and the dealer Ferdinand Möller of February and March 1929, his friend asked him for two paintings from before the war: Street with Red Streetwalker and Russian Dancer. Kirchner enclosed in his reply to Möller photos of the aforementioned works for him “to show to those interested.” On 30 March 1929 Möller wrote to Kirchner enquiring about the possibility of sending him the paintings so that they could be viewed by the collector Hermann Lange of Krefeld, who had shown an interest in purchasing them. However, it has not been possible to ascertain whether the painting was eventually sold or returned to the artist.

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.

Joy: 36.34%

Disgust: 2.68%

Contempt: 7.43%

Anger: 20.28%

Fear: 6.67%

Surprise: 6.99%

Sadness: 19.6%