Abstraction

Together with his studio colleague Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning was one of the initiators of American Abstract Expressionism. Born in the Netherlands, in 1926 he emigrated to the United States, where his painting was soon influenced by both the Cubist construction of space that was then becoming fashionable on the American art scene and the automatism of the Surrealists Miró, Arp and Matta. Nevertheless, he combined these influences with in-depth personal experimentation, particularly in colour.

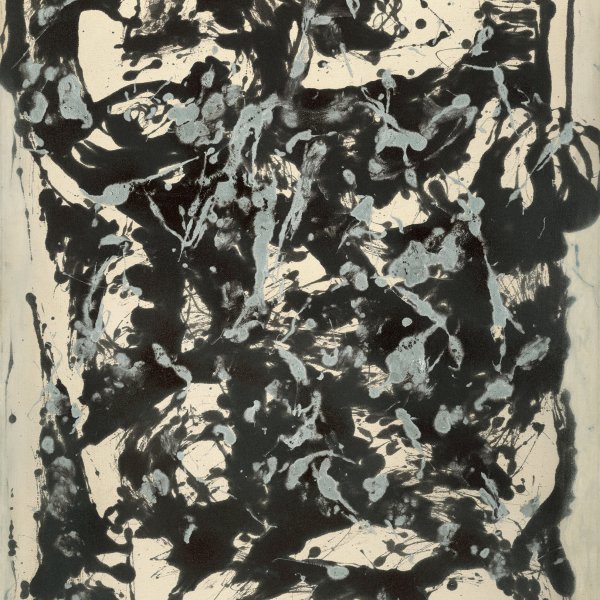

In the present Abstraction, painted in 1949‒50, De Kooning reveals a new conception of painting based on gesture and colour — an accomplished style of his own that is far removed from any previous modern language. It was executed shortly after his first one-man exhibition in New York, in which his abstract black paintings caused a sensation, and after being invited by Josef Albers to teach at Black Mountain College in the summer of 1948, where he began to introduce colour into his works.

Despite being entitled Abstraction, this composition is based on traditional pictorial motifs and, like most of the painter’s works, is infused with figurative references. As Clement Greenberg stated, “de Kooning proposes a synthesis of modernism and tradition, and a larger control over the means of abstract painting that would render it capable of statements in a grand style equivalent to that of the past.” The artist himself commented on one occasion: “I’m not interested in ‘abstracting’ or taking things out or reducing painting... I paint this way because I can keep putting more things in it — drama, anger, pain, love, a figure, a horse, my ideas about space.”

The iconography of death, present in the skull in the lower right corner and the symbolic representation of Golgotha in the ladder and post to the right of the composition, contrasts with the unusually distorted and brutal pink and yellowish flesh tones. The ladder, which appears in several paintings dating from the same period, had been used by the painter previously in 1928 in a small composition that recalls Paul Klee and Joan Miró.

The force and mobility of the planes and figures, rendered with a very violent pictorial gesture, result in a confusing image of life and death constructed from abstractions of elements taken from visual reality or from the artist’s imagination. The diagonal planes, the architectural elements with which he organises the space and structures the composition, lend it a certain three-dimensionality, but the hint of perspective is concealed by a whole host of gestural and menacing biomorphic patches. The angular shapes superimposed with curving, organic forms that allude to the human anatomy create a network of compact masses joined by various diagonal lines drawn with great spontaneity.

From the late 1940s onwards gesture and action became the chief components of De Kooning’s painting. Action, which the critic Harold Rosenberg defined as the physical act of creation, is found here in instinctive brushstrokes, impasto depictions and fingerprints. It should not be forgotten that although De Kooning himself stated that it was Pollock who “broke the ice” and revolutionised the world of art with his first drip paintings, he went on to clarify, “but I gave him the hint.”

Paloma Alarcó