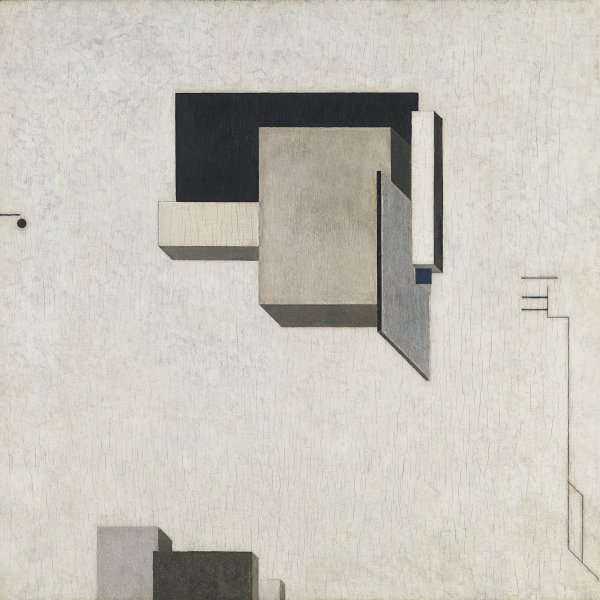

Suprematist Drawings

ca. 1919

Pencil on Paper.

21.5 x 15 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

658

(1981.24

)

Not on display

Level 2

Permanent Collection

Level 1

Permanent Collection

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Level -1

Temporary exhibition rooms, Conference room and EducaThyssen workshop

The years spanning from the outbreak of the Great War in 1914 to immediately after the Revolution of 1917 were a particularly intense period in the development of the Russian avant-gardes. The revolutionary atmosphere spurred the quest for a new art that gave priority to pure geometric shapes as opposed to figurative art, since, as the new political and economic ideology proclaimed, it was necessary to break with the past. Kazimir Malevich, one of the pioneers of geometric abstract art, was the organiser of 0.10. The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings, which opened in December 1915 in

Petrograd, at a stone’s throw from the Winter Palace, and marked the official launch of the new non-objective Russian revolutionary art. Malevich showed a large group of abstract paintings, among them

Black Square, and Tatlin exhibited his first counter-reliefs derived from Picasso’s three-dimensional Cubist constructions. That year Malevich and Mayakovsky published the Suprematist manifesto, which stated: “Everything which determined the objective-ideal structure of life and of ‘art’— ideas concepts and images — all this the artist has cast aside in order to heed pure feeling.”

Departing from investigations of Cubism and Futurism, Suprematism, which takes its name from the Latin word supremus (supreme, absolute), aimed to gradually reduce painting to its minimum expression, which Malevich achieved in 1918 with his series of “white on white” paintings. The new Suprematist and Constructivist movements also dreamed of transforming the world, abolishing all laws, and, as John Bowlt points out, they became “agents of anarchy” and “forecast the demise of the European bourgeois order, identifying the Great War and the Bolshevik coup as catalysts to social transformation.” Malevich soon became one of the leaders of the cultural revolution that marked the first years of the Bolshevik Government and produced numerous Suprematist designs for poster advertisements, theatre sets and architectural projects.

This small work featuring a series of Suprematist drawings, which belonged to Malevich’s student Anna Leporskaia, has been dated by John Bowlt and Nicoletta Misler to about 1919 on the grounds of its connection with a lithograph from the album Suprematism, published in 1920.

Paloma Alarcó

Departing from investigations of Cubism and Futurism, Suprematism, which takes its name from the Latin word supremus (supreme, absolute), aimed to gradually reduce painting to its minimum expression, which Malevich achieved in 1918 with his series of “white on white” paintings. The new Suprematist and Constructivist movements also dreamed of transforming the world, abolishing all laws, and, as John Bowlt points out, they became “agents of anarchy” and “forecast the demise of the European bourgeois order, identifying the Great War and the Bolshevik coup as catalysts to social transformation.” Malevich soon became one of the leaders of the cultural revolution that marked the first years of the Bolshevik Government and produced numerous Suprematist designs for poster advertisements, theatre sets and architectural projects.

This small work featuring a series of Suprematist drawings, which belonged to Malevich’s student Anna Leporskaia, has been dated by John Bowlt and Nicoletta Misler to about 1919 on the grounds of its connection with a lithograph from the album Suprematism, published in 1920.

Paloma Alarcó