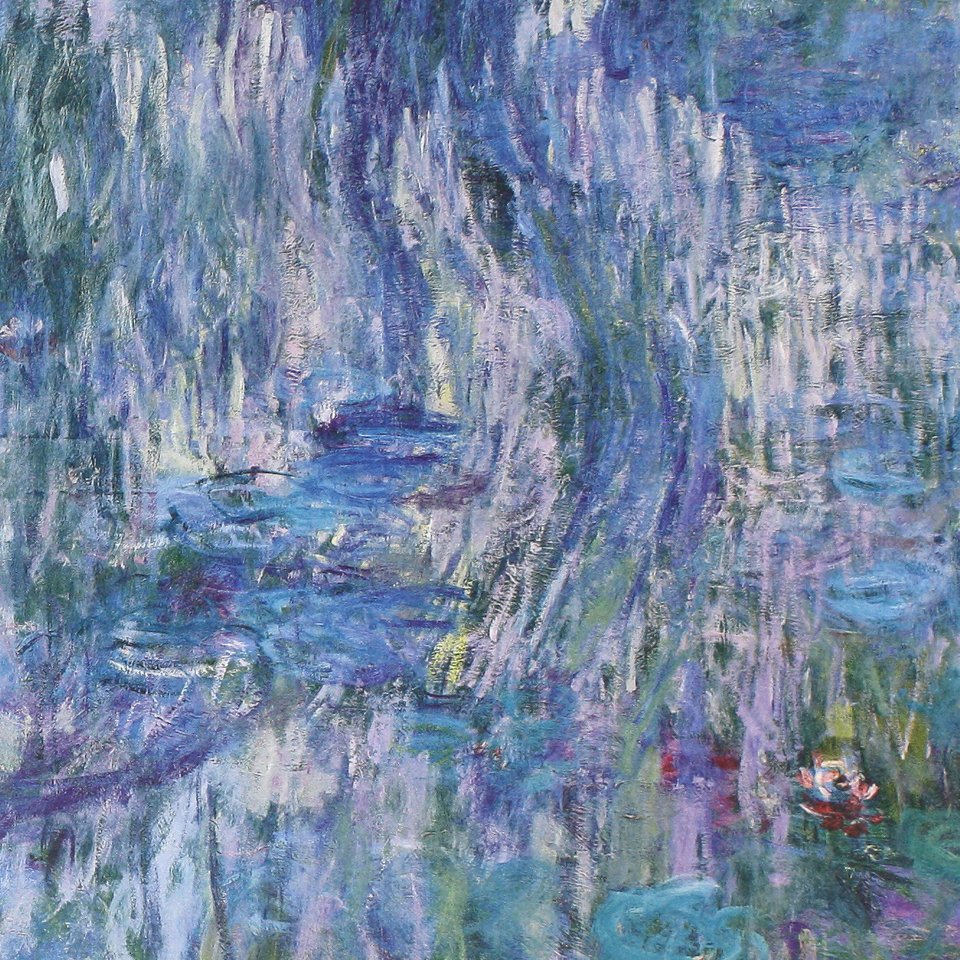

The Thaw at Vétheuil

The Thaw at Vétheuil forms part of the series of canvases painted by Claude Monet at the time when the ice began to break up in the Seine after the river had frozen in the winter of 1879. Always keen to record the ephemeral, ever-changing appearance of water, the artist sought here to capture the break up of the frozen layer into ice floes which were then carried downstream by the current.

The landscape format highlights the dominant horizontal composition, broken only by the vertical thrust of the trees and their downward reflection in the water. Using loose, deft brushstrokes and a reduced palette, Monet creates a hazy effect that accentuates the bleakness of this harsh winter landscape, conveying a sense of desolation and melancholy.

The Thaw at Vétheuil belongs to a set of seventeen oil paintings on the thaw of the Seine after the great freezes of winter 1879. The months of December 1879 and January 1880 were so cold that Paris and the surrounding area practically ground to a halt owing to the numerous snowfalls and heavy frosts caused by abnormally extreme temperatures. The Seine was completely frozen over at the small village of Vétheuil, sixty kilometres north of the capital, where the painter was living at the time. Monet, who always showed a keen interest in depicting the fleeting and changing nature of water, aimed to capture the moment when the ice split into pieces on account of the rising temperature and was carried downstream by the current. His neighbour and future companion Alice Hoschedé explained this phenomenon very graphically in a letter to her husband, then in Paris: “I was awakened by a terrible noise similar to the rumbling of thunder; [...] I rushed to the window and, in spite of the deep darkness, one could see the white masses dashing along downstream; this time it was the thaw, the real one.”

All the paintings in the series attest to Monet’s preference for horizontal planes. In these works he used particularly elongated formats to further emphasise the dominant horizontal of the compositions that is interrupted only by the verticals of the shrubs and trees and their reflections in the water. The artist takes full advantage of the vagueness of the scene, employing loose, rapid brushstrokes and a reduced palette to exaggerate the harshness of that winter, which was described as Siberian, and succeeded as never before in capturing a winter atmosphere that conveys feelings of neglect and melancholy. The silence and calm transmitted by these paintings bring to mind the artist’s sadness following the recent, early death of Camille, his wife.

In the catalogue raisonné of Monet’s work the painting is dated to 1880 and included among those probably sold by the artist to Durand-Ruel in February 1881. Possible explanations for the fact that the canvas is signed and dated 1881 may be that, as on other occasions, the signature was added at the time of the sale, or that Monet did not actually paint it outdoors while the thaw was taking place but some time later, in his studio.

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.