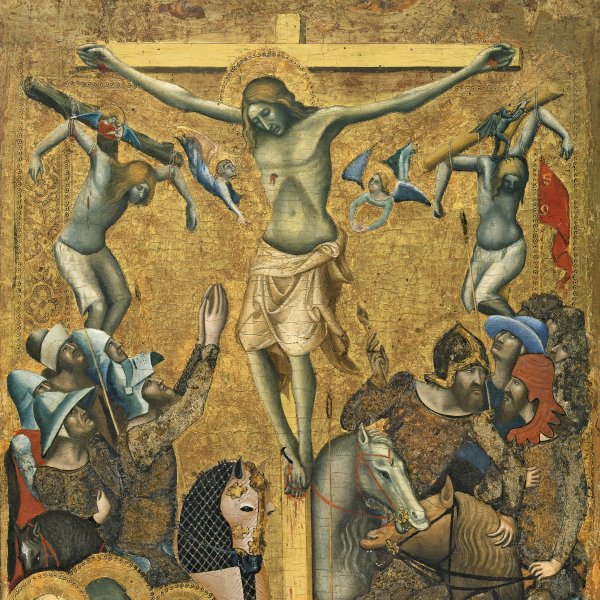

The Crucifixion with the Virgin, Saint John and Angels

ca. 1330 - 1335

Tempera and gold on panel.

135 x 89 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

412

(1968.3

)

ROOM 1

Level 2

Permanent Collection

Little is known regarding the life of this Sienese painter, and once again Vasari must be used as a source of information. Ugolino may have trained in the family workshop as his father was a painter. He very probably continued his training in the workshop of Duccio as he is considered to be one of that artist’s most outstanding followers. Among the works attributed to Ugolino is the high altarpiece in Santa Croce, Florence, dated around 1325, the panels of which are now to be found in various museums. All the above information has been used to establish a body of work and a chronology for this artist.

For unknown reasons, the present panel was cut down at the lower half as both Mary and Saint John were originally full-length, standing on either side of the cross. A painting now in a private collection in Florence reproduces this panel on a smaller scale and thus provides us with an idea of its original appearance. These two crucifixions reveal slight differences in their iconography, such as the lack of angels in the panel in the Florentine collection, the different construction of the haloes and the arrangement of one of the Virgin’s hands, as well as other elements relating to technique. The oldest known provenance for the present panel possibly suggests that it belonged to the monastery of San Francesco in San Romani, Empoli. It would seem, although it is not certain, that after the monastery was closed down it passed to the Museo Civico in Pisa, and from there entered the collection of Giuseppe Toscanelli, where it is recorded around 1883. The painting was acquired by Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza in 1968.

Known in the literature since 1883, the panel was published as a work by Duccio. This attribution was suggested again many years later, in 1966, by Parronchi, who also suggested that it might have formed part of the Maestà by that artist. In an article published in the Art Bulletin in 1955, Gertrude Coor-Achenbach attributed the panel to Ugolino di Nerio, a suggestion supported by most specialist authors.

In the present day the Crucifixion is considered to be one of Ugolino di Nerio’s finest works from his mature period, imbued with the spirituality and emotion typical of his art. On this occasion the painter opted for a pyramidal composition whose top is formed by the upper part of the cross and whose base is the figures of the Virgin and Saint John, completed by a circle closed by the six angels around Christ. Christ is nailed to a schematic base painted in blue, which the artist has outlined with a fine white line. The plaque on the cross, painted in silver, possibly has the inscription INRI. Christ’s thin but muscular body is constructed from subtly graduated planes with a delicate emphasis on some aspects of the anatomy such as the stomach and ribs. The artist shows Christ as still bleeding from some of his wounds, particularly on his side, thus emphasising the figure’s suffering condition. Only the Virgin and Saint John are present at this crucifixion and their pain and suffering are conveyed by the artist with enormous restraint. Both incline their heads to the right, counterbalancing the position of Christ’s. While the figures in this part of the panel are able to control their emotions, this is not the case with the angels, whose sad faces clearly express their despair and consternation at what has happened. This sentiment also seems to be conveyed in their draperies, which fold in dynamic billows around their feet.

Despite the losses visible at the lower edge, the panel is in a stable physical condition. The most damaged areas, such as the Virgin’s cloak, the upper arm of the cross and Christ’s left hand, do not affect the key parts of the composition.

Mar Borobia

For unknown reasons, the present panel was cut down at the lower half as both Mary and Saint John were originally full-length, standing on either side of the cross. A painting now in a private collection in Florence reproduces this panel on a smaller scale and thus provides us with an idea of its original appearance. These two crucifixions reveal slight differences in their iconography, such as the lack of angels in the panel in the Florentine collection, the different construction of the haloes and the arrangement of one of the Virgin’s hands, as well as other elements relating to technique. The oldest known provenance for the present panel possibly suggests that it belonged to the monastery of San Francesco in San Romani, Empoli. It would seem, although it is not certain, that after the monastery was closed down it passed to the Museo Civico in Pisa, and from there entered the collection of Giuseppe Toscanelli, where it is recorded around 1883. The painting was acquired by Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza in 1968.

Known in the literature since 1883, the panel was published as a work by Duccio. This attribution was suggested again many years later, in 1966, by Parronchi, who also suggested that it might have formed part of the Maestà by that artist. In an article published in the Art Bulletin in 1955, Gertrude Coor-Achenbach attributed the panel to Ugolino di Nerio, a suggestion supported by most specialist authors.

In the present day the Crucifixion is considered to be one of Ugolino di Nerio’s finest works from his mature period, imbued with the spirituality and emotion typical of his art. On this occasion the painter opted for a pyramidal composition whose top is formed by the upper part of the cross and whose base is the figures of the Virgin and Saint John, completed by a circle closed by the six angels around Christ. Christ is nailed to a schematic base painted in blue, which the artist has outlined with a fine white line. The plaque on the cross, painted in silver, possibly has the inscription INRI. Christ’s thin but muscular body is constructed from subtly graduated planes with a delicate emphasis on some aspects of the anatomy such as the stomach and ribs. The artist shows Christ as still bleeding from some of his wounds, particularly on his side, thus emphasising the figure’s suffering condition. Only the Virgin and Saint John are present at this crucifixion and their pain and suffering are conveyed by the artist with enormous restraint. Both incline their heads to the right, counterbalancing the position of Christ’s. While the figures in this part of the panel are able to control their emotions, this is not the case with the angels, whose sad faces clearly express their despair and consternation at what has happened. This sentiment also seems to be conveyed in their draperies, which fold in dynamic billows around their feet.

Despite the losses visible at the lower edge, the panel is in a stable physical condition. The most damaged areas, such as the Virgin’s cloak, the upper arm of the cross and Christ’s left hand, do not affect the key parts of the composition.

Mar Borobia