The Harvesters (Les Moissonneurs)

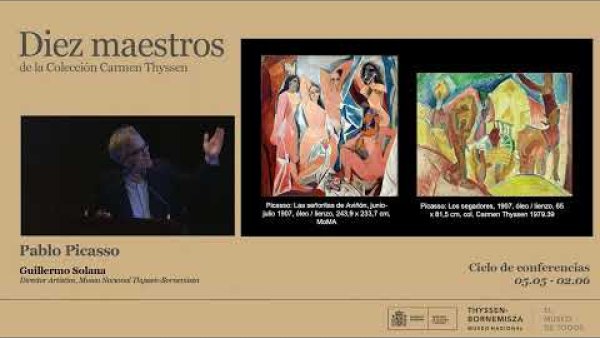

Like other painters in his circle, Picasso was keen to find new techniques that would enable him to handle large compositions with numerous forms. His experiments produced four major canvases painted between 1906 and 1907: The Harem, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, The Peasants and The Harvesters. Whereas in the first two the characters are arranged within an enclosed space, suggesting sickness and degradation, in the last two the free movement of the figures within a rural environment suggests the opposite: health and harmony. In terms of form, the figures in The Harvesters are also more clearly seen as separate characters than Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, since Picasso was experimenting with an essentially two-dimensional approach. In this respect, there are obvious echoes of Matisse, although Picasso uses more strident colours.

The Musée Picasso in Paris owns a large format drawing (48.2 x 63 cm) in charcoal with strong outlines which seems to be the final sketch of the painting we are analysing. C. Rafart mentions the existence of several drawings related to some of its figures in the preparatory notebooks for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Daix and Rosselet link it to a small group of works, very likely painted later, one of which is an oil painting and the others are watercolours. Daix states that in 1970 Picasso had confirmed to him that he had painted The Harvesters in the Bateau-Lavoir studio, while he was working on Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. In Green's opinion, it must have been during the second phase of this painting's execution, namely at the end of June or the beginning of July 1907. He bases his argument on the generally accepted dating of Notebooks 12 and 14. In them we find drawings for the curtains of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, whose geometrical pattern is almost identical to that of this landscape. Yet those drawings are probably subsequent to The Harvesters; therefore, in my opinion, the suggested dates (end of June or beginning of July) should be taken as an ante quem reference.

Several authors have pointed out the relationship between The Harvesters and the works painted by Picasso in Gósol in the summer of 1906. Like Green, I think the most obvious precedent of The Harvesters is The Peasants, the large painting belonging to the Barnes Foundation that Picasso finished in Paris in August 1906, immediately after his return from Gósol. Indeed, there are two elements that link these two works: first, the arrangement of the two oxen is very similar and this is quite significant, bearing in mind that animals are very seldom depicted in Picasso's works during those years; second, the predominance of the colour yellow to represent wheat, a meaningful detail even for the artist, who referred to it in the very brief description of The Peasants, in a letter addressed to Leo Stein dated 17 August 1906.

If to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, The Harvesters and The Peasants we added The Harem, we would have the four works painted between the summer of 1906 and the summer of 1907, when Picasso undertook complex compositions with several figures. This grouping is important because, at the time, the Parisian avant-garde artists shared the opinion that the aim of new 20th-century art was to find modern formulas for this kind of composition. Apparently, the precedents of Gauguin and Cézanne pointed in that direction; in fact, a series of works ranging from The Joy of Life and Derain's The Golden Age, both from 1905, up to The Dance, from 1909-1910, reveal how compelling this opinion was within the artistic circle Picasso had just joined in 1906.

Green groups these four works into two pairs: The Harem and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon on the one hand, and The Peasants and The Harvesters on the other. In the first group the figures are depicted indoors; in the second, in a landscape. To the connotations of violence, degradation and sickness that could be associated with the urban environment of The Harem and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, we could oppose those of harmony, purity and health identified with the rural environment of The Peasants and The Harvesters.

Green also analyses the position of these works in the evolution of Cubism, a question amply debated in art historiography. The argument that Les Demoiselles d'Avignon should be considered as the foundational work of cubism was first set forth by Kahnweiler and later developed by Barr in 1939, in the catalogue of the first retrospective exhibition of Picasso organised by the Museum of Modern Art, New York, shortly after this museum acquired the painting. This opinion has been refuted by Rubin (1977 and 1988) and by Daix (1979 and 1988). According to these authors Les Demoiselles d'Avignon should be interpreted as the expression of the primitivist trend that Picasso shared with Derain and Matisse from 1906 to 1907. Cubism strictly speaking saw the light in 1908, as a result of Braque and Picasso's stronger artistic affinity. When executing his L'Estaque landscapes in the summer of 1908, Braque may have discovered in the Cezannian technique of the passages a solution for the conflict raised by the contrast between figure and background on one hand, and the new demands for bidimensionality or "flatness" of the pictorial space on the other.

Taking up Barr's theory, Green suggests that Les Demoiselles d'Avignon should be considered again as the origin of Cubism. Without dismissing the importance of the Cezannian passages, he considers there is another essential component of Cubism, namely the tendency to a geometrical schematisation of volumes, clearly present already in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon; this tendency is much more evident in this work precisely whencompared to the rhythmic bidimensionality of The Harvesters.

In my opinion, it is undeniable that, throughout the development of Picasso's Cubism, there is a highly persistent duality between a tendency that we could call "sculptural" and one towards "flatness"; in the latter, the bidimensionality of the pictorial space is reinforced and the figures are subordinated to the geometrical composition of the painting. Very often these two tendencies come into conflict and the works shift towards one extreme or the other; if they move towards the former, the risk from an artistic point of view is lack of unity; if they shift towards the latter, the danger is to fall into decorativism. The successive attempts to reach a synthesis between these two tendencies mark the gradual development of the pictorial language of Cubism. In this sense, if we consider the painting Three Women, from the autumn of 1908, we can find in it a synthesis of the sculptural tendency present in Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the rhythmical tendency of Femme à la draperie, both from 1907. The impression one gets when looking at Femme à la draperie is that of a marked flatness, a feature which becomes stronger when this painting is compared with Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Yet in this comparison we notice that both works share a stylistic feature whose aim is solely to achieve a certain degree of synthesis between the "sculptural" and the "atmospheric" elements: the resort to Primitivism.

Now, if we go back to the spring of 1907, the contrast between the "sculptural" aspect of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the "flatness" of The Harvesters was gradually solved with other stylistic resources, the origin of which is to be found in Picasso's reaction to the paintings by Matisse and Derain exhibited in the Salon des Indépendants in March 1907. His reaction was a mixture of his interpretations of Ingres, Cézanne and Gauguin, which Picasso shared with Matisse and Derain, and his own personal interpretation of El Greco.

The remote but significant influence of El Greco on the origins and the development of Cubism has traditionally been acknowledge in the bibliography. In the 1950s, Picasso himself stated that El Greco had been a precursor of Cubism. Barr includes the mannerist language of El Greco among his main sources of inspiration for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. In recent historiography the links between this picture and El Greco's painting have somehow faded, with the exception of Richardson, who insists on them and points out a precise reference in a large composition by the Cretan master, The Opening of the Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse, acquired by Zuloaga in the summer of 1906, which Picasso no doubt had seen during his frequent visits to the Basque painter's studio. Daix, for his part, underlines the influence of El Greco in The Peasants. In my opinion, there are equally valid reasons for seeing traces of El Greco in The Harvesters, chronologically conceived between that work and Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. Thus, in the main figure in our painting, the peasant walking towards the front of the composition with his arms raised, we can see a rather faithful transposition of the young man, also with his arms raised, on the left of The Opening of the Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse. Even more significant from a pictorial point of view is the treatment of space in The Harvesters, with distortions and discontinuities in the perspective which recall El Greco's mannerist composition.

The influence of Ingres, already visible in Picasso's paintings of the spring, and even more of the summer of 1906, became more intense in 1907. In The Harvesters Picasso adopts again the vanishing point shifted towards the left and the high point of view he had used in The Harem and which in this painting seems to have been inspired by Ingres's The Turkish Bath. The two figures in the background, on the left, closing the diagonal compositional line of The Harvesters are an almost unmodified variant of the two figures in the background, on the left, closing the composition of The Harem. The connection of these two works with Ingres' painting has been repeatedly mentioned in recent bibliography. Yet in The Harvesters Gauguin's mark is more evident than that of Ingres. The prevalence of the pictorial plane over the third dimension is achieved by enhancing the lines that divide the coloured areas, and forming a rhythmical arabesque with a result that recalls the cloisonné in enamels. It is well known that this was a device developed by Gauguin and widely used by his followers.

In any case, the weight of the influence of Ingres and Gauguin on the works painted by Picasso between 1906-1907 should be analysed in the light of his relationship with Matisse and Derain. Probably Daix and Rosselet had in mind this relationship when they stated that The Harvesters "is Picasso's only real fauve painting". This opinion, unanimously supported by subsequent historiography, might well have its origin in Picasso himself or in people very close to him. In what constitutes the first bibliographic reference of this painting, the Spanish art critic Rafael Benet identifies it, not by its title but as "the fauve painting we are reproducing". Daix, who has splendidly summarised the relationship between Picasso and Matisse, states that Picasso had assured him that at the time nobody had studied Matisse's oeuvre as deeply as him. Therefore, if we wish to understand the context of The Harvesters, we should analyse the main landmarks in Matisse's evolution and (to a lesser extent) in that of Derain between 1906 and 1907. In Matisse's case, we are referring to the path that leads from The Joy of Life, a work exhibited in the 1906 Salon des Indépendants, to The Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra), exhibited in the same Salon in 1907; in Derain's case, that from The Dance, 1906, to the first version of Bathers, also shown in the 1907 Salon.

Le Bonheur de vivre had marked Matisse's definitive move away from neo-Impressionist influence. If we compare this painting with Luxe, calme et volupté, 1904, we will find in Le Bonheur de vivre two elements of style which explain Signac's indignation when he saw it in the Salon des Indépendants: the use of sinuous forms in order to achieve the impression of spatial depth (after the manner of Ingres) and the replacement of the neo-Impressionists' divided brushstroke and "scientific" colour with a free brushstroke and a subjective, expressive use of colour. Yet the neo-Impressionist palette as such, with a range of colours harmoniously distributed throughout the spectrum, from violet to bluish green, then shifting to reds and yellows, had hardly changed. In Derain's The Dance the distance from the neo-Impressionists was even greater, and Gauguin's influence much stronger; but it is above all the primitivism-reinforced to the point of paroxysm-of this powerful composition what probably impressed Picasso when he saw it in the autumn of 1906; the Spanish artist's reaction would become clear a few months later-Daix explains-when, in the second phase of the execution of Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Picasso took his own primitivism to a paroxysmal degree.

Derain's Bathers and Matisse's The Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra), both exhibited in the Salon des Indépendants in March 1907, represent a radicalisation of the search for a new pictorial space. Matisse's work was probably the one that most attracted Picasso. In The Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) Matisse abandoned the neo-Impressionist palette and reached a convincing synthesis between Gauguin's flatness and Cézanne's volumetry. Before executing this painting, Matisse had experimented with the perspective deformities in nudes, by modelling a sculpture; thus he responded (for the first time) to Picasso, and perhaps more particularly to Deux Femmes Nues, a work executed by the Spanish painter in the autumn of 1906. But while Picasso's figures stand out against a neutral background, Matisse had successfully integrated his nude in the pictorial space by using two devices: the rhythmical correspondence (after the manner of Gauguin) between the nude's lines and the background vegetation, and the distribution of the blue around the volume outlines, in a way that seemed to anticipate the systematic development of the Cezannian passages by Braque and Picasso himself in 1908.

The fact that Picasso adopted rather literally these two technical devices in The Harvesters indicates that the date of this painting must have been subsequent, though close, to March-April 1907. It is even possible that at some point he considered The Harvesters as the most relevant response to Matisse. Compared with Le Bonheur de vivre, this composition is equally complex, although it shows greater unity. On the other hand The Harvesters attains a greater rhythmical integration of the pictorial plane (after the manner of Gauguin) than that of The Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra). The ogival curves that, in Matisse's painting, close the space at the top cover all the surface of Picasso's picture. In the centre of the composition, the cartwheel introduces a motif whose dynamic effect anticipates some paths that the Parisian artistic avant-garde would not explore until 1910. Finally, as regards colour, Picasso, as Matisse had previously done in Le Bonheur de vivre, used violet to indicate distance (in the background figure of the woman carrying a basket on her head) contrasting it, as did the fauves, to yellow; but, by replacing the reds with ochres and browns, he broke away from neo-Impressionist chromatic harmony and in fact proposed chromatic dissonance as the standard of modernity.

Although the project of The Harvesters did not crystallise in a large format painting like Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, it clearly had a fruitful influence on a crucial point of the development of avant-garde painting. Derain would explore its effects on the landscapes he executed in Cassis in the spring of that same year, enhancing them a few months later in the second version of Bathers. In fact, the cloisonné technique would become an important stylistic component of what Apollinaire was to call "Cubism" in Derain's painting. On the other hand, the fact that the avant-garde painting of the last years of that decade moved away from the neo-Impressionist and fauve palette has a clear precedent in The Harvesters. Matisse himself, in one of his most Gauguinian compositions, Le Luxe I, painted in 1907, used violet for the background, combined with blues, yellows and browns, as Picasso had done in The Harvesters.

Yet the fertility of the experience of The Harvesters was to become clearest in the oeuvre of Picasso himself. The ogival patterns can be seen in several preparatory sketches for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, and became an important element in Nude with Drapery, a painting in which the curved angles cover, like a net, the totality of the pictorial plane. Several studies of nudes executed the following year and, above all, the oil entitled Three Women; rhythmical version, move along the same line. At the beginning of the following decade, other artists, from Delaunay to Franz Marc, undertook the task of deviating this path towards the experimental field of abstract painting; in the work of Picasso, a painter who always distrusted abstraction, that rhythmical trend merged in the Cubist mainstream.

Tomàs Llorens