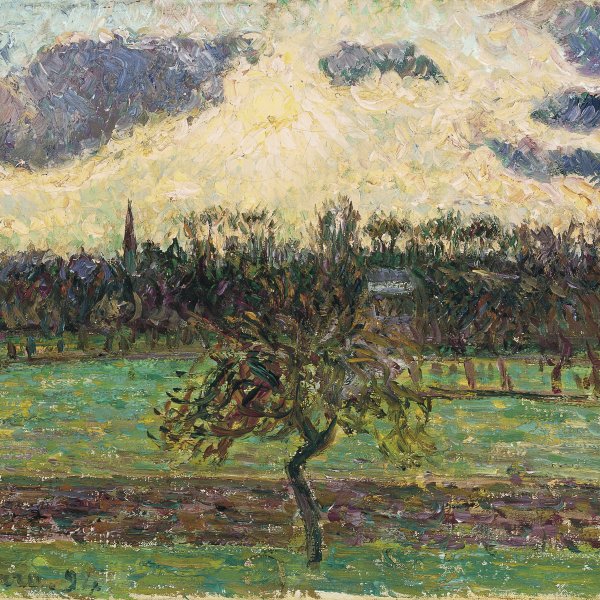

The Cabbage Field, Pontoise

In contrast to Monet, Sisley and Renoir’s scenes of bourgeois leisure, Camille Pissarro preferred to depict rural settings. The village of Pontoise, 35 km from Paris, was one such place. Pissarro lived there between 1872 and 1882 and painted more than three hundred landscapes, all located within a very small area.

When Cabbage Field, Pontoise was included in the first Impressionist exhibition of 1874, critics referred to the vulgarity of the cabbages in the foreground. In fact, the principal motif of this work is the morning mist that envelops the forms and which Pissarro captures with a technique mid-way between Corot’s use of monochrome and Impressionism’s open brushstroke. In addition, the artist made use of a solid compositional structure based on horizontals and verticals that is comparable to the great classical tradition of French landscape painting. The result is a serene, harmonious work in which time seems to stand still.

JAL

Cézanne at the same period was working on a series of roughly textured, chromatically dense paintings of similar rural motifs, and these culminated in the famous Maison du Pendu (Paris, Musee d'Orsay) which made its debut in the Impressionist exhibition of 1874. Although none of them share the same motif as this painting by Pissarro, many of them face the same pictorial problems, which are innumerable. What the two men did was to select motifs of an almost extreme banality and with few prospects of pictorial "success." By courting such banality, the artist himself takes on the brunt of the process of pictorial seduction normally shared with an attractive or appealing motif.

To paint the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza painting, Pissarro walked about five minutes from his house to a section of Pontoise called "le Chou", the time is probably October or early November, the fruit tree in the foreground has already lost its leaves, but many of the bigger hardwood trees on the hillside are still foliated. He also selected a time at the very end of the day, when the rays of the sun on the rest enter "stage right" casting long shadows across the foreground and illuminating very little of the densely forested hillside that is the central "motif" of Pissarro's painting. The alluvial fields of the Chou are in their winter mode, with mature cabbages in the foreground alternating with other crops like potatoes that have already been ploughed-under. A field of winter grasses for grazing is illuminated by the light on the far right, and the sky is the pale golden-grey of wintery dusk. There is, thus, an immense pictorial challenge in making this mostly green and dull landscape "come alive" through the act of representation.

Three figures give scale and purpose to the landscape. One tiny woman, a rural worker carrying something she has just harvested, faces us, forcing us into an active role as viewers. A second, a male worker, bends over in work in the middle ground, perhaps pulling turnips or, more likely, picking up firewood. The third, a female reduced to a tiny stroke of blue-grey paint in the forest just behind the largest figure, has gathered and is carrying faggots from the forests for the evening fire. Unlike the peasant figures of Millet, these recede into the depths of the landscape, refusing to allow a human narrative to disrupt our quiet contemplation of this rural autumn evening.

What is remarkable about the painting is how "slow" it is. The dark purplish-grey shapes of the houses on the top of the hill are not those of the cheery new maison de campagne painted by Monet, Renoir, and Sisley in the same year. They are, rather, the humble dwellings of rural workers whose ancestors had toiled these fields for more than a millennium. Only the "time of day"-dusk-is short, and we know that night will fall within a quarter of an hour as it has for as long as similar rural workers have performed similar tasks in similar fields. This is not the "momentary" time of the urban bourgeoisie with their trains, boats, and leisure-not, in other words, "Impressionist" time. It is, rather, a slow, recurrent time of la France profonde, and, as we look at this painting, we too slow down.

The very idea of this painting and of many others made by Cézanne and Pissarro during this winter season is that the painter works to represent the ultimate "truth" of appearance and that we viewers, whether exhibition-goers or prospective purchasers, work too to comprehend that truth. Nothing is easy-neither painting nor viewing-in this humble rural world with no evident appeal to the urban bourgeoisie for whom the paintings are made. And, to return to the double signatures of this and other paintings from 1873-1874, this "difficulty" is recognised, indeed almost advertised, by the painter. Not content with his first efforts, he, nevertheless, "confesses" his doubts by working again on the painting until he can, after another bout of work, signal its "completion" by signing and dating it on the opposite corner. We take the pale grey-blue signature, "C. Pissarro, " without a date in the lower left corner as the earlier. The second, "1873 Pissarro, " which is a wonderful colour that almost approaches apricot, is prefaced not by the artist's first initial, but by the date, and the colour of this signature can only be found in the painting in the sky.

What prompted Pissarro to do this? Perhaps he had walked to Auvers and looked at Cézanne's work (or the converse), and looked at a similar wintery sky that "worked" more successfully in a painting by the younger artist. Perhaps Pissarro had walked by the motif one early evening and felt, in standing there, that his first attempt to represent this delicate and difficult effect of light had failed, so he started again on the sky. We shall never know exactly the motivation, but we do know, because of the double signature, that he had improved his painting after its first "completion, " raising in our minds the question of what he changed and why he changed it. How interesting it would be for historians of Impressionism for a major museum to gather these "double dated" pictures of doubt so that we can have first-hand evidence of the pictorial struggle engaged in willingly by Cézanne and Pissarro in 1872-1874.

Richard R. Brettell