Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain

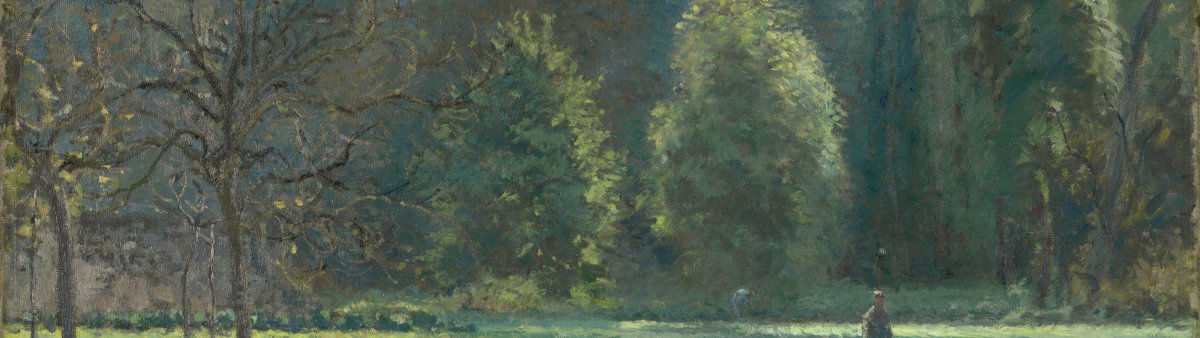

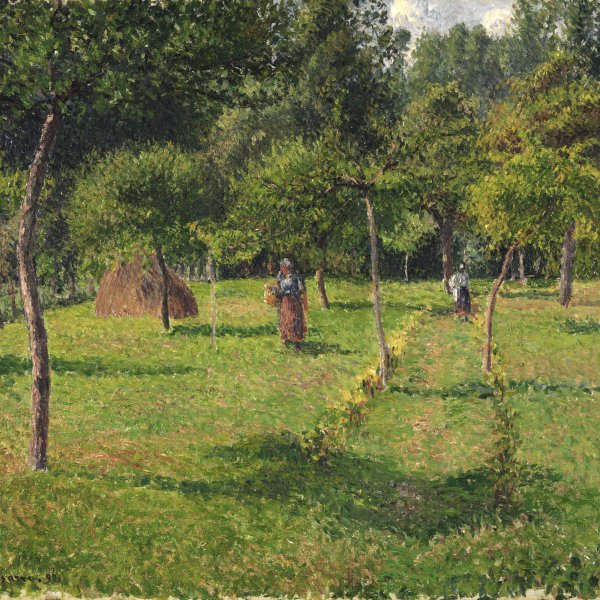

Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain belongs to a series of fifteen works that Camille Pissarro painted in Paris from the window of his hotel in the place du Théâtre Français during the winter of 1897 and 1898. Pissarro, who had spent practically all of his life in the country and was basically a landscape painter — and one of the first convincing practitioners of plein air painting — was forced to move to the city for health reasons towards the end of his life. It was then that he began to paint urban scenes viewed from windows, capturing the bustle of the streets of cities like Rouen and Paris. Stylistically, this last decade of his life coincides with his return to an Impressionist technique after experimenting with the influence of Seurat for a short period. Pointillisme, which he abandoned owing to its excessive rigidity, helped him lighten his palette and compose his last paintings in a less rigorous manner.

Pissarro worked enthusiastically on this cycle on the streets of Paris, no doubt encouraged by Durand-Ruel’s promise that he would show them at his gallery. He chose one of the new urban settings created during the Second Empire (1852–70) by Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, who, not without triggering major controversies, had made Paris a modern city crossed by broad avenues that provided long vistas along their different axes. In this series the artist not only painted every view available from his room — the rue Saint-Honoré, the avenue de l’Opera and the square itself next to the hotel — but reworked the same compositions under different lighting conditions.

The pictorial model for urban scenes painted from a high viewpoint had been established by Monet in his famous Boulevard des Capucines, which was shown in the First Impressionist Exhibition of 1874. Painted a year earlier from the window of Nadar’s studio, it is a lasting image of the new bustle of the city. The high viewpoint provided by Paris’s new buildings gave the composition a casual air and more natural appearance that was more in keeping with the Impressionists’ aim of painting real-life scenes.

In the three paintings he produced of the rue Saint-Honoré, Pissarro provides a perspectival view of this street with the corner of the place du Théâtre Français in the foreground. Like Monet, he employs a high viewpoint, taking advantage of the angles of vision in the foreshortening. He establishes a play of circular and rectangular forms; of verticals formed by trees and streetlamps crossed by the diagonal of the elongated street, the final stretch of which is a sort of optical illusion.

The scene depicted in the work in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza is one of early afternoon. There are several horse-drawn carriages in the street and the pedestrians, from a variety of social classes, are treated individually and not as a mass. It has been raining and a few drops are still falling, which is why a few passers-by have their umbrellas up. In another version the scene is illuminated by the powerful morning sunlight and in the third version the dim dusk light casts a shadow over the city.

The high viewpoint was a device the painter also used to distance himself from the scene. This approach, which Pissarro employed for urban themes, differs from that of landscapes and rural scenes, which he painted from a closer viewpoint in order to express the contrast between country and city life. It should not be forgotten that Pissarro’s last works coincide with his adoption of an increasingly radical ideology that brought him progressively closer to the anarchist movement. In accordance with these political ideas, the rural world was presented as a model of a harmonious lifestyle, as an idyllic representation of a new Arcadia. Pissarro viewed the city from a certain distance and assumed the role of the Baudelairean flâneur. With his prodigious powers of observation, he provides us with a pictorial evocation of new city life: “Perhaps it is not aesthetic, but I am delighted to be able to paint these Paris streets that people have come to call ugly [...] This is completely modern!” The relationship between the modernisation of the French capital under Napoleon III and the new Impressionist painting is expressed to perfection here.

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.