Express

Together with Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg provided a link between the generation of more veteran Abstract Expressionist painters and the young Pop artists. Although Rauschenberg always maintained certain elements of Abstract Expressionism in his oeuvre, he rebelled against it at the same time. His meeting with Marcel Duchamp in 1960 was decisive in his adoption of Dadaist methods. Duchamp also admired these young Americans, who turned their backs totally on tradition to create their works: “In Europe, ” he stated, “the Young artists of any generation always act like the grandson of some great man or other — Poussin, for example, or Victor Hugo. This is not the case here. Here they don’t give a fig about Shakespeare, no one is his grandson. Thus the terrain is more suitable for new discoveries.”

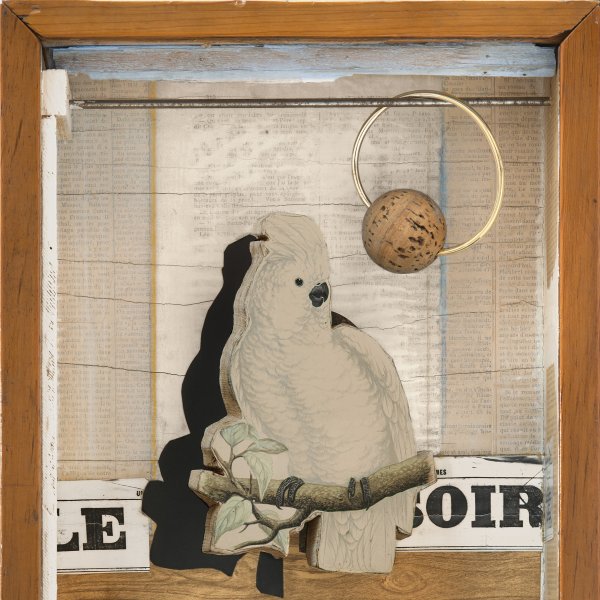

Midway through the 1950s, Rauschenberg began to produce his Combines — a mixture of painting, assemblage and collage — from found photographs and objects, usually consumer society trash. In 1962, under the influence of Andy Warhol, he began to experiment with a new type of artistic technique which became the basis of his work during the following years: silkscreen printmaking. This method enabled him to incorporate photographic images printed on silk screens that he then transferred to canvas, manipulating them and superimposing them in the manner of collages; he then completed the effect with oil painting.

Enlarged reproductions of photographs of his or of magazine cuttings were systematically repeated in different works. As a result of being enlarged to a much bigger scale than the original, the images have a grainy appearance which Rauschenberg exploits by combining them with thick, rapid brushstrokes of oil paint. As can be read in the artist’s testimony recorded by Calvin Tomkins, this technique fascinated him for its element of surprise and for the countless possibilities offered by an image when manipulated and combined with others, as well as for the manner in which “some images insist on being themselves, do what you will to them.”

The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Express belongs to a group of paintings in which Rauschenberg uses silkscreen printing. Some of the photographs reproduced in it, which capture his visual universe, are found in earlier and later works. According to Gail Levin, the title Express may allude both to very fast movement and to something very precise and exact, or even to the expression of a particular creative impulse. There are numerous references to movement in the work: the repeated image of the horse and rider about to jump over an obstacle, the dancers in action, the climber hanging from his rope, the wheels in the lower part of the picture and a nude descending a staircase — a very explicit reference to Duchamp’s famous work that was shown in the Armory Show in 1913. The photograph of the dancers is a tribute to Rauschenberg’s choreographer friend Merce Cunningham, a fellow student at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, an experimental school that undoubtedly contributed to the development of Rauschenberg’s unique artistic language.

Rauschenberg was always a multidisciplinary artist. Whatever the kind of work he produced, he always remained faithful to his spirit of criticism of the established norms and experimental zeal. Express was one of the works shown in the American pavilion of the Venice Biennale of 1964, where Rauschenberg was the first American artist to be awarded the First Prize. Thenceforward the public recognition of his oeuvre, which constantly sought new forms of expression in art, made him one of the most influential of the young artists of the final decades of the twentieth century.

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.