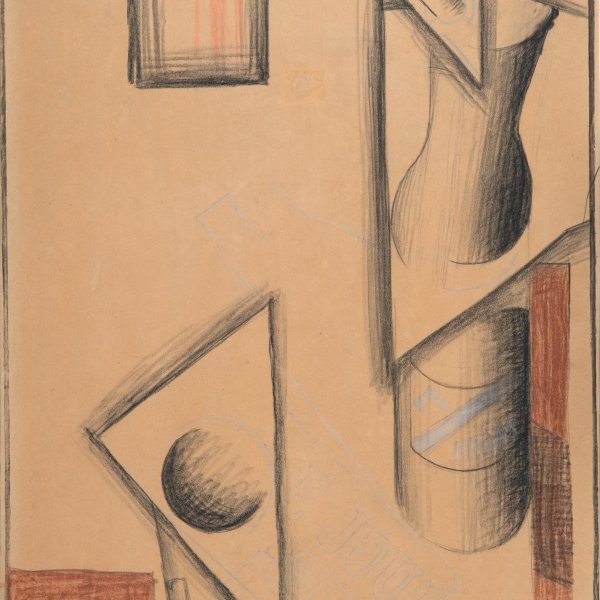

Expansion of Light. (Centrifugal and Centripetal)

ca. 1913 - 1914

Oil on canvas.

65 x 43.3 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

752

(1981.53

)

ROOM 42

Level 1

Permanent Collection

The decomposition of forms, introduced by Cubism, influenced both Robert Delaunay’s new abstract language based on light and colour and the artistic doctrine of the Italian Futurists exalting the fast pace of modern life. Severini, who arrived in the French capital in 1906, following Boccioni’s footsteps, succeeded in combining the aesthetic concerns of Orphism and Futurism and became an essential link between French and Italian artists. He wrote in his autobiography, published in 1946, that “the cities to which I feel most strongly bound are Cortona and Paris: I was born physically in the first, intellectually and spiritually in the second.” Although he considered himself a member of the Futurists — he signed all the successive manifestos and took part in all the group’s exhibitions — his work clearly displays the influence of the art of the French painters Delaunay and Léger.

The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Expansion of Light (Centrifugal and Centripetal) is also a good example of Severini’s abstract Divisionism, which exploits the effects of the luminous vibration of colour. Daniela Fonti refers to a letter written by to Giuseppe Sprovieri from Anzio on 6 February 1914 mentioning two works in which he composes the forms through the immateriality of light — Espansione sferica della luce, centrípeta and Espansione sferica della luce, centrifuga — which were sent to the Galleria Futurista for the exhibition due to be held there that month. Fonti considers that one might be the painting in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza on account of both its style and its format. However, the original title of the work in the collection, Expansion de la lumière (Centrifuge et centripède), inscribed by the artist himself on the back of the canvas, leads Christopher Green to conclude that it is more likely to be a synthesis painted at a later date than the paintings entitled Spherical Expansion.

Constructed exclusively from the three primary colours and their complementary shades using a Divisionist technique derived from the Neo-Impressionism of Seurat, which infuses the composition with greater luminosity, the present painting contrasts the different speeds of vibration depending on their position in the colour wheel. As Nicole Tamburini points out, Severini makes use of colour theories in such a way that “close colours (yellow and orange) vibrate rapidly when juxtaposed and form dissonances, whereas complementary colours (yellow and violet) when placed together vibrate slowly and establish consonances.” Severini’s tendency towards Divisionism is undoubtedly related to the re-edition in 1911 of Paul Signac’s treatise D’Eugène Delacroix au Néoimpressionnisme (1899), which afforded him in-depth knowledge of the theories of colour. Maurice Tuchman discusses the importance of the influence of symbolism and spiritualism on the Futurist aesthetic and considers that “the Expansion of the Light series would not have led to the dissolution of materiality without influence from spiritualism.” He likewise adds that the transparency of bodies, especially in Futurism, stems from the influence of photography, but also from occultist ideas about invisible beings.

The combination of cubic and circular forms helps create a dynamic effect of the universe. During the years he lived in the French capital, Severini regularly frequented music halls and other nightspots and many of his compositions from the Expansion of Light series reproduce the movements of the dancers’ colourful dresses through the spherical expansions of light and colour, based on the two-pronged legacy of Delaunay’s simultaneous contrasts and Léger’s mechanised forms. On occasions this set of paintings has been related to Sea=Dancer of 1914, a work begun in Italy at the end of 1913, in which he compares the swirling movements of the dancers with the movements of the sea. Here, the curling planes in fluid colours and the rhythms of the figure expand beyond the limits of the painting owing to Severini’s conviction that light is a universal force and an energy that expands in space. He wrote in Les Analogies plastiques dans le dynamism that “a spheric expansion of colour is achieved in perfect harmony with the spheric expansion of forms, ” adding that “one can have in the same picture several centrifugal and centripetal groups in simultaneous and dynamic concurrence.”

Paloma Alarcó

The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Expansion of Light (Centrifugal and Centripetal) is also a good example of Severini’s abstract Divisionism, which exploits the effects of the luminous vibration of colour. Daniela Fonti refers to a letter written by to Giuseppe Sprovieri from Anzio on 6 February 1914 mentioning two works in which he composes the forms through the immateriality of light — Espansione sferica della luce, centrípeta and Espansione sferica della luce, centrifuga — which were sent to the Galleria Futurista for the exhibition due to be held there that month. Fonti considers that one might be the painting in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza on account of both its style and its format. However, the original title of the work in the collection, Expansion de la lumière (Centrifuge et centripède), inscribed by the artist himself on the back of the canvas, leads Christopher Green to conclude that it is more likely to be a synthesis painted at a later date than the paintings entitled Spherical Expansion.

Constructed exclusively from the three primary colours and their complementary shades using a Divisionist technique derived from the Neo-Impressionism of Seurat, which infuses the composition with greater luminosity, the present painting contrasts the different speeds of vibration depending on their position in the colour wheel. As Nicole Tamburini points out, Severini makes use of colour theories in such a way that “close colours (yellow and orange) vibrate rapidly when juxtaposed and form dissonances, whereas complementary colours (yellow and violet) when placed together vibrate slowly and establish consonances.” Severini’s tendency towards Divisionism is undoubtedly related to the re-edition in 1911 of Paul Signac’s treatise D’Eugène Delacroix au Néoimpressionnisme (1899), which afforded him in-depth knowledge of the theories of colour. Maurice Tuchman discusses the importance of the influence of symbolism and spiritualism on the Futurist aesthetic and considers that “the Expansion of the Light series would not have led to the dissolution of materiality without influence from spiritualism.” He likewise adds that the transparency of bodies, especially in Futurism, stems from the influence of photography, but also from occultist ideas about invisible beings.

The combination of cubic and circular forms helps create a dynamic effect of the universe. During the years he lived in the French capital, Severini regularly frequented music halls and other nightspots and many of his compositions from the Expansion of Light series reproduce the movements of the dancers’ colourful dresses through the spherical expansions of light and colour, based on the two-pronged legacy of Delaunay’s simultaneous contrasts and Léger’s mechanised forms. On occasions this set of paintings has been related to Sea=Dancer of 1914, a work begun in Italy at the end of 1913, in which he compares the swirling movements of the dancers with the movements of the sea. Here, the curling planes in fluid colours and the rhythms of the figure expand beyond the limits of the painting owing to Severini’s conviction that light is a universal force and an energy that expands in space. He wrote in Les Analogies plastiques dans le dynamism that “a spheric expansion of colour is achieved in perfect harmony with the spheric expansion of forms, ” adding that “one can have in the same picture several centrifugal and centripetal groups in simultaneous and dynamic concurrence.”

Paloma Alarcó

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.

Joy: 37.84%

Disgust: 9.23%

Contempt: 0.41%

Anger: 6.16%

Fear: 19.87%

Surprise: 19.3%

Sadness: 7.19%