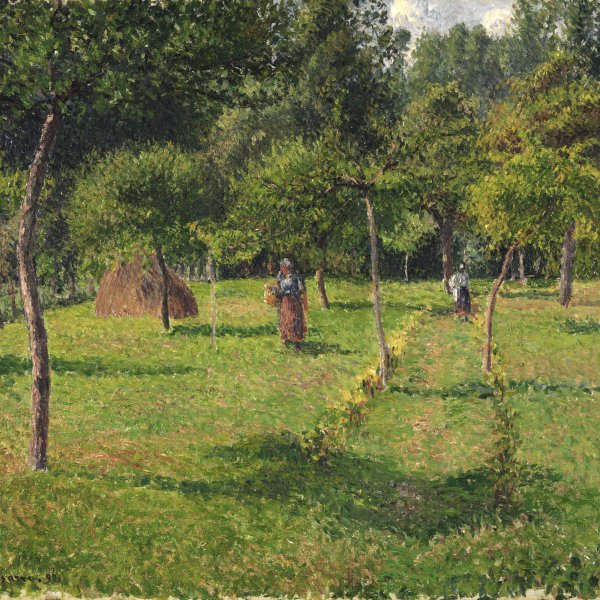

A Turn of the River Loing. Summer

1896

Oil on canvas.

54 x 65.4 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.1998.40

)

ROOM D

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

A Turn of the River Loing, Summer belongs to a group of some 21 works (D 847-864, 882-884) which Sisley created in 1896 and 1897, the last two productive years of his career. With the exception of the paintings made during his Welsh trip from July to October 1897 (including D865-881), these late works drew their subject matter from the environs of Moret-sur-Loing. However, rather than continuing the «visual mapping» of the town, its bridge and water mills, and its immediate river banks lined with poplar trees (see Evening in Moret, end of October, D 685), they explore the configuration of the banks of the River Loing dressed with denser wooded areas and free from human habitation with the exception of wooden cabins erected for boat building and barge repair which figure in four of them (D 853, 855-857).

The paintings essentially fall into two groups. Four of them (D 847, 851-853) present the River Loing and the river bank beyond as two areas lying parallel to the picture plane, the trees of the river bank beyond countering the forceful horizontality of the composition through the repeated vertical rhythm of their reflections in the water. The second group, to which A Turn of the River Loing. Summer belongs, employs the compositional convention regularly used by Sisley throughout his career, of a river curving away from the foreground to establish the direction and speed of recession into the depth of the composition. In both groups the concentration of wooded areas lies on the far river bank. However, in this second group, the foreground tends to be animated by figures, as in A Turn of the River Loing. Summer, and by the presence of barges and small craft either plying the river, as in D 848, 858, 860, 862, 883 and 884, or moored beside the bank, as in D 848-850, 860, 861 and 863.

The general tonalities of these late works created along the banks of the River Loing demonstrate a further development in Sisley´s inquiries into the relationship between the light in the sky, its translation into colour which both describes a specific landscape´s physical properties and communicates a poetic or emotional charge generated by the artist´s personal response to it. Around 1880, Sisley, in response to the challenge thrown down to the Impressionists by Emile Zola, the novelist, critic and erstwhile supporter, began to question some of the fundamental principles of Impressionism. This not only led him initially to introduce juxtapositions of brighter, purer hues, as in the foreground of Village sur les bords de la Marne (Saint-Mammès) (1881, D 422; Pittsburgh (PA), The Carnegie Art Institute), but also to emphasise the dominance of complementary colours, such as the division into blue and orange zones of the autumnal landscape, Le Chemin de By au bois des Roches-Courtaut-Eté de la Saint-Martin (1881, D 433; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal).4 Over the intervening decade prior to the creation of these late works, Sisley´s palette, brushwork and compositional procedures sought to establish a balance between the record of a fleeting moment in time and a greater sense of stability which echoed the underlying permanence of Nature. The works of 1896 and 1897, including those made during the Welsh trip, with their more muted tones of greens, greys and lilacs, episodically punctuated by recessive oranges, as in A Turn of the River Loing. Summer, their consistency of shorter brushstroke and their more structured horizontal and diagonal compositions reflect both a culmination of these explorations and hint at possible new directions that were to remain unrealised due to Sisley´s untimely death in January 1899 shortly before his 60th birthday.

Sisley appears to have been satisfied with the new direction that his subject matter and tonal harmonies had taken from 1896 since he chose to include three views along the River Loing (D 848, 855, 857) made in 1896 in his last major retrospective exhibition held at Galerie Georges Petit, rue de Sèze, Paris, from 5 to 28 February 1897. This exhibition was of capital importance to Sisley. Not only did he include 146 paintings and five pastels, selecting them from his own stock as well as borrowing important works from such collectors as Charpentier, Decap, Bazalgette, Tavernier and Viau, but he also declined, exceptionally, to exhibit that year with the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (le Salon du Champ de Mars), the annual salon with which he had shown his work since its foundation in 1890.5 As was so often the case for Sisley, the exhibition generated little critical reaction and no sales. Arsène Alexandre felt that the exhibition lacked discipline in the number of works shown: «To say the truth, the number could have been restricted, and the exhibition would have had a greater effect if the choice had been made more rigorously.» However, he recognised that Sisley, the landscapist, was a pure painter who expressed throughout all his work an evident pleasure in the process of painting: «But what comes out from this set is a strong impression of freshness and a clear joy of painting, without reservation. Sisley should not be expected to have the powerful audacity of Monet, or the exquisite elegance of Renoir. He paints with pleasure, and for the pleasure of painting». Indeed, despite the critical controversy which surrounded Sisley´s later work, encapsulated in Octave Mirbeau´s dismissive evaluation of 1892, which declared that, «[his] brush is weakening, his draughtsmanship is slackening. A sense of discouragement is felt throughout his work... The paintings he offers us today are but the distant, feeble echo of those, so pretty, so youthful, so alive, that I can still see at the back of my enthusiastic, but already ancient, memories.» These last works suggest the discovery of a mature, more reflective vision of nature, transmitted through a calmer, more meditated choice of subject matter, as is demonstrated in both the palette and composition of A Turn of the River Loing, Summer. It was these works which provided the ultimate motifs which enabled Gustave Geffroy to summarise in 1923 Sisley´s unique contribution to the Impressionist movement: «He was, and will always be, the charming poet of the river banks, and of those towns which spread their fresh and quiet beauty along the verges of the Seine and of the Loing, like Saint-Mammès, where he lived for a long time, and Moret, where he died, and where his monument is now.»

Mary-Anne Stevens

The paintings essentially fall into two groups. Four of them (D 847, 851-853) present the River Loing and the river bank beyond as two areas lying parallel to the picture plane, the trees of the river bank beyond countering the forceful horizontality of the composition through the repeated vertical rhythm of their reflections in the water. The second group, to which A Turn of the River Loing. Summer belongs, employs the compositional convention regularly used by Sisley throughout his career, of a river curving away from the foreground to establish the direction and speed of recession into the depth of the composition. In both groups the concentration of wooded areas lies on the far river bank. However, in this second group, the foreground tends to be animated by figures, as in A Turn of the River Loing. Summer, and by the presence of barges and small craft either plying the river, as in D 848, 858, 860, 862, 883 and 884, or moored beside the bank, as in D 848-850, 860, 861 and 863.

The general tonalities of these late works created along the banks of the River Loing demonstrate a further development in Sisley´s inquiries into the relationship between the light in the sky, its translation into colour which both describes a specific landscape´s physical properties and communicates a poetic or emotional charge generated by the artist´s personal response to it. Around 1880, Sisley, in response to the challenge thrown down to the Impressionists by Emile Zola, the novelist, critic and erstwhile supporter, began to question some of the fundamental principles of Impressionism. This not only led him initially to introduce juxtapositions of brighter, purer hues, as in the foreground of Village sur les bords de la Marne (Saint-Mammès) (1881, D 422; Pittsburgh (PA), The Carnegie Art Institute), but also to emphasise the dominance of complementary colours, such as the division into blue and orange zones of the autumnal landscape, Le Chemin de By au bois des Roches-Courtaut-Eté de la Saint-Martin (1881, D 433; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Montréal).4 Over the intervening decade prior to the creation of these late works, Sisley´s palette, brushwork and compositional procedures sought to establish a balance between the record of a fleeting moment in time and a greater sense of stability which echoed the underlying permanence of Nature. The works of 1896 and 1897, including those made during the Welsh trip, with their more muted tones of greens, greys and lilacs, episodically punctuated by recessive oranges, as in A Turn of the River Loing. Summer, their consistency of shorter brushstroke and their more structured horizontal and diagonal compositions reflect both a culmination of these explorations and hint at possible new directions that were to remain unrealised due to Sisley´s untimely death in January 1899 shortly before his 60th birthday.

Sisley appears to have been satisfied with the new direction that his subject matter and tonal harmonies had taken from 1896 since he chose to include three views along the River Loing (D 848, 855, 857) made in 1896 in his last major retrospective exhibition held at Galerie Georges Petit, rue de Sèze, Paris, from 5 to 28 February 1897. This exhibition was of capital importance to Sisley. Not only did he include 146 paintings and five pastels, selecting them from his own stock as well as borrowing important works from such collectors as Charpentier, Decap, Bazalgette, Tavernier and Viau, but he also declined, exceptionally, to exhibit that year with the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (le Salon du Champ de Mars), the annual salon with which he had shown his work since its foundation in 1890.5 As was so often the case for Sisley, the exhibition generated little critical reaction and no sales. Arsène Alexandre felt that the exhibition lacked discipline in the number of works shown: «To say the truth, the number could have been restricted, and the exhibition would have had a greater effect if the choice had been made more rigorously.» However, he recognised that Sisley, the landscapist, was a pure painter who expressed throughout all his work an evident pleasure in the process of painting: «But what comes out from this set is a strong impression of freshness and a clear joy of painting, without reservation. Sisley should not be expected to have the powerful audacity of Monet, or the exquisite elegance of Renoir. He paints with pleasure, and for the pleasure of painting». Indeed, despite the critical controversy which surrounded Sisley´s later work, encapsulated in Octave Mirbeau´s dismissive evaluation of 1892, which declared that, «[his] brush is weakening, his draughtsmanship is slackening. A sense of discouragement is felt throughout his work... The paintings he offers us today are but the distant, feeble echo of those, so pretty, so youthful, so alive, that I can still see at the back of my enthusiastic, but already ancient, memories.» These last works suggest the discovery of a mature, more reflective vision of nature, transmitted through a calmer, more meditated choice of subject matter, as is demonstrated in both the palette and composition of A Turn of the River Loing, Summer. It was these works which provided the ultimate motifs which enabled Gustave Geffroy to summarise in 1923 Sisley´s unique contribution to the Impressionist movement: «He was, and will always be, the charming poet of the river banks, and of those towns which spread their fresh and quiet beauty along the verges of the Seine and of the Loing, like Saint-Mammès, where he lived for a long time, and Moret, where he died, and where his monument is now.»

Mary-Anne Stevens