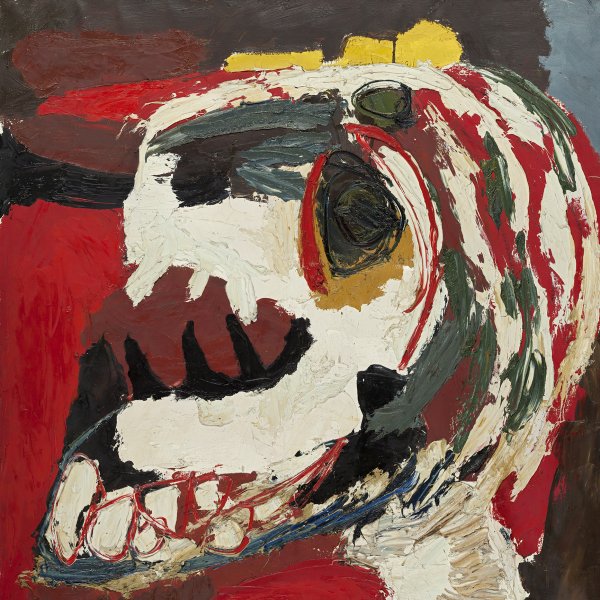

Mediterranean Landscape

1953

Oil on canvas.

33 x 46 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

763

(1961.12

)

Not on display

Level 2

Permanent Collection

Level 1

Permanent Collection

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Level -1

Temporary exhibition rooms, Conference room and EducaThyssen workshop

At the beginning of the 1950s, when the Art Informel movements were in full swing, the painter Nicolas de Staël abandoned his previous gloomy abstraction and returned to a more figurative and luminous style with which he attempted to evoke his visual experiences by capturing certain chromatic resonances on canvas. The present Mediterranean Landscape is a good example of his new quest to reconcile figuration and abstraction and of his insistence on the need to combine abstract forms — the essential elements of any painting — with the capturing of a visual reality.

The landscape, executed with considerable economy of means in heavy impasto, is a luminous view of the coast of Provence in bluish and greyish tones. The composition is structured around horizontal planes of geometrical forms created by a build-up of grey, blue and ochre impasto with which he constructs the different elements of the landscape. Using barely four or five planes of colour, Staël depicts the basic features of the landscape: a house, two trees, the sky and the sea. The glowing light of the French Midi transforms the colours of his palette, and the blue of the Mediterranean stands out in the centre of the composition above all the rest. Similarly, as Douglas Cooper points out, the Mediterranean landscapes of these years display the hint of a certain linear perspective, generally directed towards a central focal point. In December 1954 Staël wrote to his dealer Jacques Dubourg: “my painting, behind its appearances, its violence, its perpetual plays of force, is something fragile in the good, sublime sense.” The richness of textures and the subtlety of the colouring reach their height of refinement in this work.

Paloma Alarcó

The landscape, executed with considerable economy of means in heavy impasto, is a luminous view of the coast of Provence in bluish and greyish tones. The composition is structured around horizontal planes of geometrical forms created by a build-up of grey, blue and ochre impasto with which he constructs the different elements of the landscape. Using barely four or five planes of colour, Staël depicts the basic features of the landscape: a house, two trees, the sky and the sea. The glowing light of the French Midi transforms the colours of his palette, and the blue of the Mediterranean stands out in the centre of the composition above all the rest. Similarly, as Douglas Cooper points out, the Mediterranean landscapes of these years display the hint of a certain linear perspective, generally directed towards a central focal point. In December 1954 Staël wrote to his dealer Jacques Dubourg: “my painting, behind its appearances, its violence, its perpetual plays of force, is something fragile in the good, sublime sense.” The richness of textures and the subtlety of the colouring reach their height of refinement in this work.

Paloma Alarcó