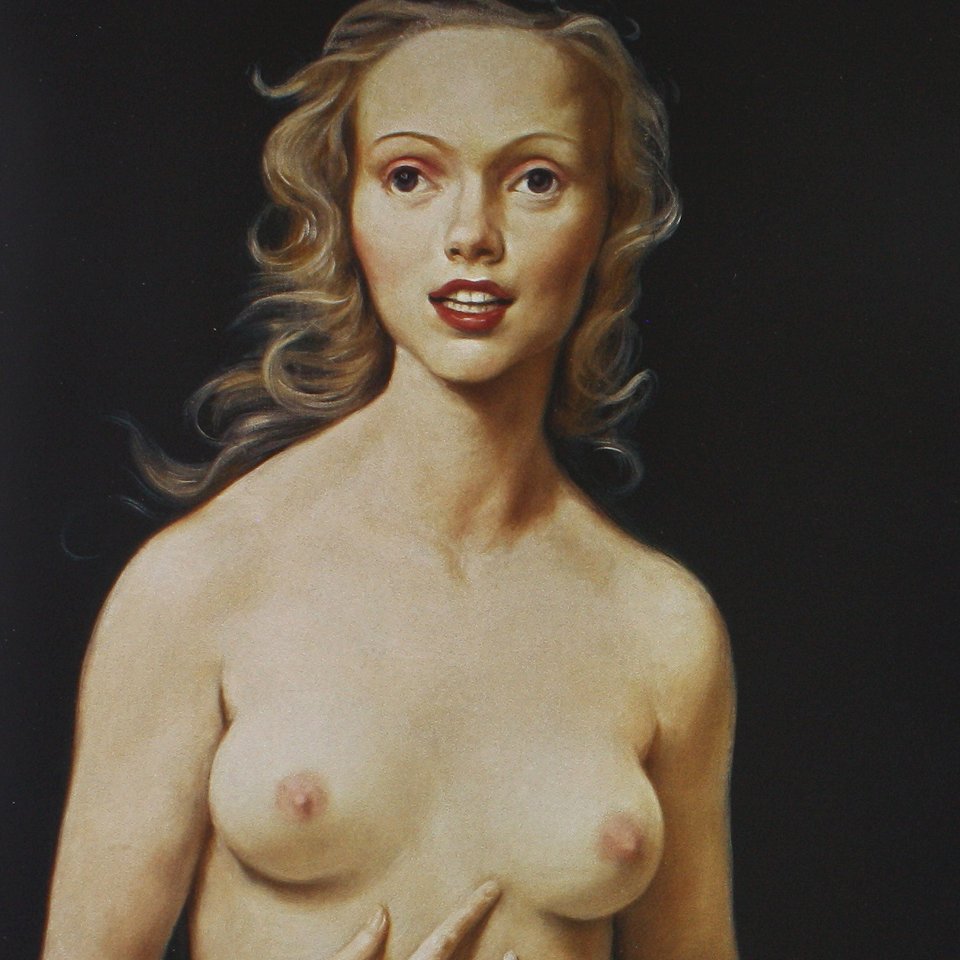

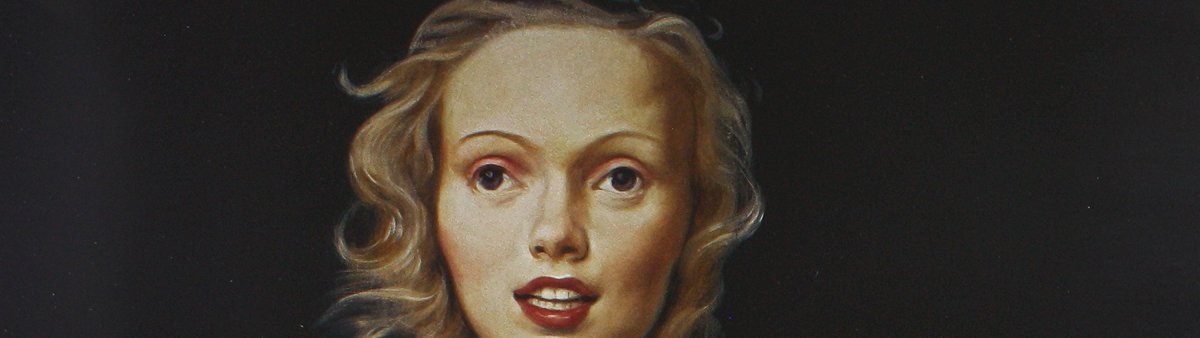

The Death of Hyacinthus

This large canvas dates from the period when Tiepolo was working in Würzburg. It was first attributed to the artist by Sack in 1910. In Würzburg, Tiepolo worked together with his two sons Giandomenico and Lorenzo on the execution of one of the most important decorative cycles of his career, namely the frescoes for the residence of the Prince-Bishop Karl Philipp von Greiffenklau, generally considered to be one of the artist’s finest projects.

The subject is taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (Book X) and relates the fatal outcome of the love of the god Apollo for the mortal Hyacinthus. According to this classical tale, Hyacinthus died as a result of his own clumsiness when he threw a discus during a competition, wounding himself mortally in the head. Another version of the tale has it that it was Apollo who threw the discus, accidentally killing the youth as it rebounded off the ground or a rock. In other versions it was the wind Zephyrus who deflected the discus towards Hyacinthus out of jealously and unrequited love. Unable to bring the youth back to life, Apollo transformed him into a flower that Tiepolo depicts in a beautiful clump in the right-hand corner.

Tiepolo offered a rather free interpretation with regard to the object that killed Hyacinthus, which here seems to be one of the tennis balls located next to a racquet beside him. A third ball, which, to judge from the position of his fingers, Hyacinthus seems to have been holding just before the accident, has rolled across the tiled floor to end up on the left of the composition. In addition, we see part of a net behind the closely packed group of onlookers on the left. This licence with regard to the story derives from the translation of Ovid of 1561 by Giovanni Andrea dell’Anguillara. In that text the discus is replaced by a tennis ball. Known at the time as pallacorda, the game was popular among the nobility in the 16th century and at the time when Tiepolo painted this canvas. The Querini Stampalia Foundation in Venice has a canvas by Gabriel Bella in which pairs of players are engaged in the sport in an enclosed court.

Overall, Tiepolo’s composition expresses that subtle sense of irony that made the artist such a great creative figure on numerous occasions. In addition to the artist’s modification of the subject, the canvas is unique in its interpretation of the composition, with a semi-nude Hyacinthus lying on the ground looking up at the anguished Apollo, the bruise on his cheek indicating his wound. The rather theatrical poses of the two principal figures are offset by those of the silent witnesses to the event, aligned on the left, and the malicious smile on the face of the statue of Pan, which seems to have turned its head so as not to miss the outcome of the story.

Various preparatory drawings are known for the central group, two of them in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which are studies for the poses of the two main figures. In one of them Hyacinthus lies on the ground with his legs together and flexed in a manner close to the final painting. In the two drawings, however, Apollo tends the wounded youth. Similarities have also been detected between this canvas and the series illustrating Gerusalemme liberate painted for Würzburg. The first composition in that series is located in the enchanted garden in which we see Rinaldo and Armida. The macaw, the piece of entablature on which it perches, the statue of Pan, the cypress trees in the background and the arch leading to the tennis court are all to be found in that composition. In the episode in which Rinaldo leaves Armida, the latter’s pose, seated on the ground in a slightly inclining position, also recalls Hyacinthus in the present painting.

The present canvas was in the collection of Baron Wilhelm Friedrich Schaumburg-Lippe in Bückeburg, and may have been acquired directly by him from the artist.While it was in the possession of his heirs, the princes of Schaumburg-Lippe, it was first included in an exhibition held in Berlin on 17th- and 18th-century Italian painting. The canvas belonged to the family until 1934 when it entered the Rohoncz collection, as the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection was formerly known.

Mar Borobia

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.

More details about The Death of Hyacinthus