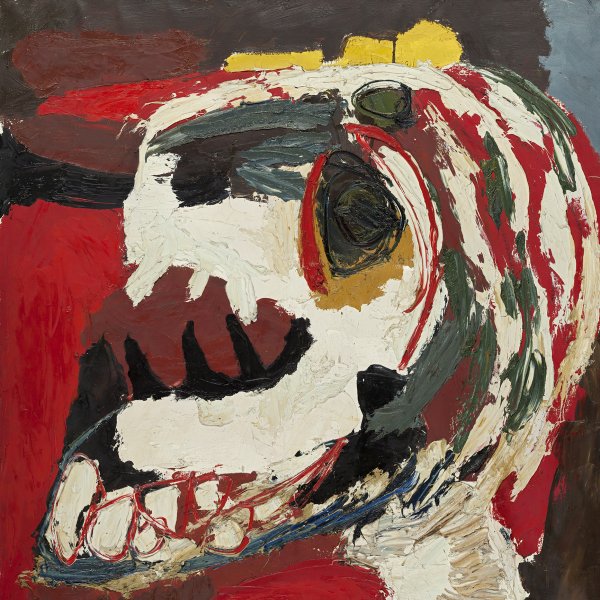

The City

1950 - 1951

Gouache, ink and watercolor on Paper.

21 x 16.5 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

786

(1975.19

)

Not on display

Level 2

Permanent Collection

Level 1

Permanent Collection

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Level -1

Temporary exhibition rooms, Conference room and EducaThyssen workshop

Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze, whose pseudonym was Wols, fled Germany in 1933 following the arrival of Nazism and spent the remainder of his short existence between France and Spain, always an outsider, living on the fringes of society. In 1951 the critic Michel Tapié included him in the 1951 exhibition Vehemences confrontées, a comparison of the non-figurative trends in French, American and

Italian painting, and he soon became one of the forerunners of informal abstraction, sometimes called Tachism.

Wols’s calligraphic abstraction — a peculiar mix of poetic, oriental and Surrealist influence — also reveals the mark of Klee’s psychic improvisation and the automatism of Miró, Tanguy and Masson, as well as the so-called psychoanalytical drawings of Jackson Pollock. However, despite sharing many features with certain informal languages, Wols, a follower of the Taoist philosopher who aspired to at-oneness with nature, never severed his links with the real world.

As evidenced in The City, a small and delicate work on paper belonging to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Wols’s cities are not idyllic places but rather, as Werner Haftmann has written, “enigmatic cities that haunted the dreams of Kafka and Kubin.” The absence of human life is offset by a phantasmagorical universe swept up in a turbulence that causes it to close in on itself. As in other watercolours from his final period, the gestural, automatic brushwork became more spontaneous and the mesh of small dots and intricate lines drawn in India ink envelop the watercolour background. Like most of his paintings, this bewildering image may be considered an expression of his state of mind, which his writer friend Jean-Paul Sartre defined in existentialist terms: “His life was like a string of battered, unmatched beads, each one of which incarnated the world. As he used to say himself, it didn’t matter where you broke the string.”

Paloma Alarcó

Wols’s calligraphic abstraction — a peculiar mix of poetic, oriental and Surrealist influence — also reveals the mark of Klee’s psychic improvisation and the automatism of Miró, Tanguy and Masson, as well as the so-called psychoanalytical drawings of Jackson Pollock. However, despite sharing many features with certain informal languages, Wols, a follower of the Taoist philosopher who aspired to at-oneness with nature, never severed his links with the real world.

As evidenced in The City, a small and delicate work on paper belonging to the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Wols’s cities are not idyllic places but rather, as Werner Haftmann has written, “enigmatic cities that haunted the dreams of Kafka and Kubin.” The absence of human life is offset by a phantasmagorical universe swept up in a turbulence that causes it to close in on itself. As in other watercolours from his final period, the gestural, automatic brushwork became more spontaneous and the mesh of small dots and intricate lines drawn in India ink envelop the watercolour background. Like most of his paintings, this bewildering image may be considered an expression of his state of mind, which his writer friend Jean-Paul Sartre defined in existentialist terms: “His life was like a string of battered, unmatched beads, each one of which incarnated the world. As he used to say himself, it didn’t matter where you broke the string.”

Paloma Alarcó