The Risen Christ

This panel depicting The Risen Christ was formerly in the collection of the Pusterla della Porta family in Milan, where it is recorded from 1590 until the first quarter of the 20th century. It was acquired for the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection in 1937, at which time it belonged to Countess Teresa Soranzo-Mocenigo, also in Milan. Since it was first published by Müller Walde in 1898 it has been the subject of various studies in which its attribution to either Bramante or Bramantino has been extensively debated. Müller Walde and the authors of the earlier catalogues of the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection attributed it to Bramante. It was Suida in 1905 who first suggested that it was by Bartolomeo Suardi, a pupil of Bramante known as Bramantino. It is now considered to be one of the latter’s masterpieces. Mulazzini dated it to around 1490 in the last phase of the artist’s career.

Bramantino had studied the work of Lombard artists and was influenced in his early career by Donato Bramante. Among the aspects of the latter’s work that most influenced him were the use of light, the linear and graphic aspects of the construction of volumes and the use of perspective. In Milan, Bramantino worked for Gian Giacomo Trivulzio for whom he designed a series of cartoons for tapestries on the months of the year. During his mature phase he developed an interest in classical culture, introducing fragments of classical buildings and sculpture into his compositions.

There has been some debate on the subject of this panel. Earlier publications and various exhibition catalogues presented it as an Ecce Homo or Man of Sorrows but the image has subsequently been interpreted as a Risen Christ, the title now given to it. The reasons for this substantial modification are based on a re-reading of the iconography. The Ecce Homo depicts Christ presented to the people following the Flagellation and Crowning with Thorns. Widely disseminated from the late 15th century onwards, it usually shows Christ with the crown of thorns on his head, bleeding and wearing a cloak, with a reed staff and his hands tied. None of these attributes are to be found in the present painting. Christ appears here frontally, displaying in an emphatic manner the wounds from the crucifixion, realistically depicted on his hands and his ribcage which is partly covered by his robe. The depiction of the wounds enables us to identify Christ as depicted after the crucifixion, not before, and to suggest that the dark structure behind him may be the tomb. On the left Bramantino depicted a river landscape with a tall-masted ship and two campaign tents topped by golden balls.

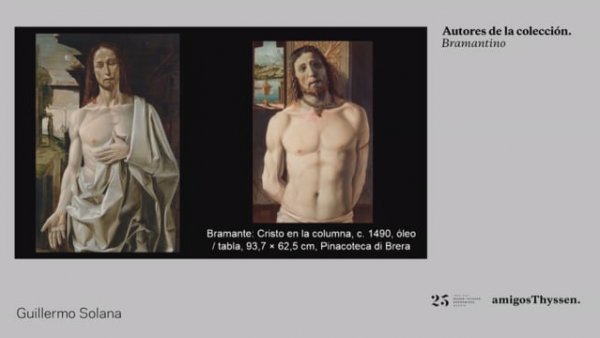

This Risen Christ by Bramantino has little to do with depictions of this subject that present Christ as triumphant over Death. Here the Saviour is depicted with red eyes and an expression of intense suffering and sadness. The body, constructed with an almost ghostly pallor, contrasts with the brighter, red tones used for the face, hair and hands. Shown standing, three-quarter length, Christ is drawn with great precision, as can be seen in the fingers, the outstretched arm and the muscles. The figure is inspired by Donato Bramante’s Christ tied to a Column, painted for the abbey of Chiaravalle and in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, since 1915. In that work Bramante was particularly interested in the interior space in which Christ is located, creating the sense of a large area through the use of architectural elements such as the pilaster to which Christ is tied, and above all the use of light. Despite the darkness surrounding the face, Christ’s expression is sufficiently powerful to focus the viewer’s attention on the realm of the emotions, which is the aspect that Bramantino wished to investigate here. The museum of the Charterhouse in Pavia has another work of slightly larger format than the present one, which repeats this composition but with slightly softer lines.

Mar Borobia

Emotions through art

This artwork is part of a study we conducted to analyze people's emotional responses when observing 125 pieces from the museum.