Thirty-three Little Girls set out for the White Butterfly Hunt

1958

Oil on canvas.

137 x 107 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

537

(1971.8

)

Not on display

Level 2

Permanent Collection

Level 1

Permanent Collection

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Level -1

Temporary exhibition rooms, Conference room and EducaThyssen workshop

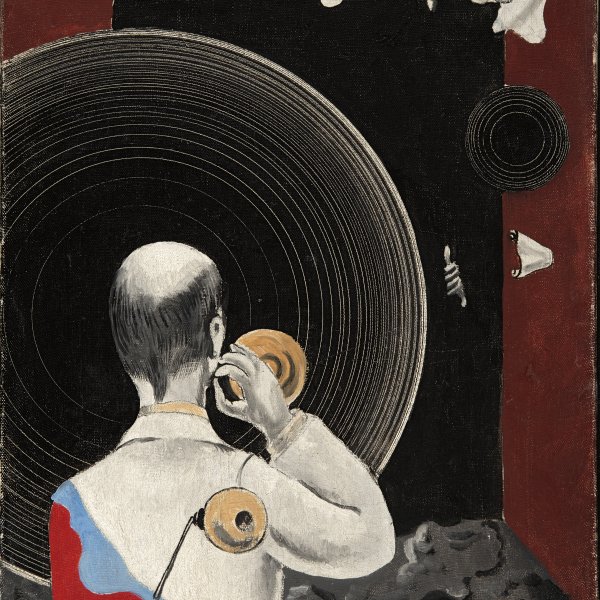

Max Ernst obtained French nationality in 1958. He and his fourth wife, the American painter Dorothea Tanning, had returned to France five years earlier and from 1955 to 1964 they lived in Huismes, near Chinon, where Ernst executed the present oil painting entitled Thirtythree Little Girls Set out for the White Butterfly Hunt, which has belonged to the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection since 1971. In this explosion of light, Ernst returns to grattage, a technique he had employed since the 1920s. Using a palette knife he applies short, broken strokes that cover practically the entire surface of the canvas and create an abstract effect. As Werner Spies has stressed, when using this procedure now, the artist places more of an accent on texture, which shows that from the 1950s his painting succumbed to the influence of the automatic techniques of Tachisme and Art Informel.

For his exhibition at the Galerie Creuzevault in Paris in 1958, where this painting was shown, Max Ernst published five poems in prose, including one entitled “Présence d’Alice” containing an explicit reference to the symbolic content of the painting: “At the junction of two signs, one for a school of herrings and the other for a school of crystals, thirty-three little girls set out for the white butterfly hunt, the blind dance in the night, princes sleep badly and the black crow is to speak.”

Paloma Alarcó

For his exhibition at the Galerie Creuzevault in Paris in 1958, where this painting was shown, Max Ernst published five poems in prose, including one entitled “Présence d’Alice” containing an explicit reference to the symbolic content of the painting: “At the junction of two signs, one for a school of herrings and the other for a school of crystals, thirty-three little girls set out for the white butterfly hunt, the blind dance in the night, princes sleep badly and the black crow is to speak.”

Paloma Alarcó