In April 1916 Juan Gris signed a contract with Léonce Rosenberg granting him ownership of his entire artistic output, both existing and future. Shortly afterwards, between the end of 1918 and beginning of 1919, the dealer organised a series of exhibitions of the work of Cubist artists at his Galerie l’Effort Moderne to prove that the avant-garde movement remained alive despite Louis Vauxcelles’s devastating criticism. As Christopher Green suggests, it is fairly likely that the Bottle and Fruit Dish in the Thyssen-Bornemisza collection was included in the exhibition of the painter’s work in April 1919, as it had belonged to the gallery’s holdings since February that year.

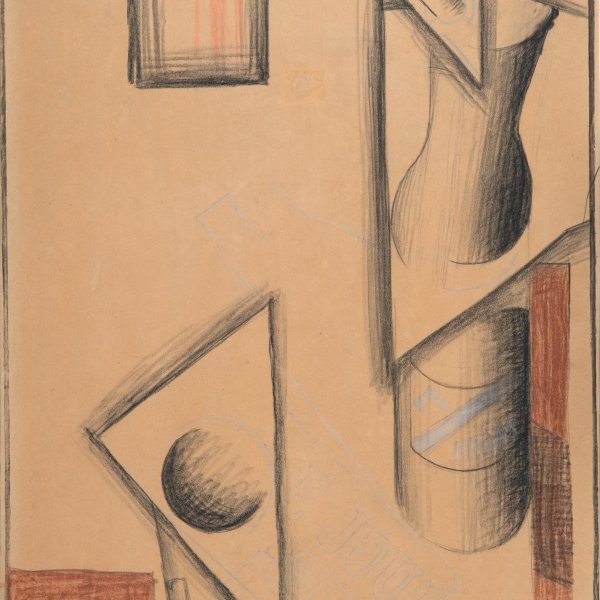

Like other still lifes painted at Beaulieu-lès-Loches, Bottle and Fruit Dish exhibits an interplay of warm brown tones combined with colder greens and greys, taken directly from the landscape. Gris expressed his wish for the colour in his painting to rival the rich hues of nature in a letter to Léonce Rosenberg dated 10 August 1918: “In the countryside I see such solid and materially sumptuous tones and such perfect combinations, that they carry within themselves a far greater force than all the combinations of the palette, and I would like to work with them.” However, in contrast to these natural tones, the simple, flat geometry of the painting and the abstraction of the objects are clearly anti-naturalistic. The arrangement of the napkin that hangs over the edge of the table, a motif borrowed from Cézanne, has an interesting significance in the context of the so-called post-war “return to order” of the avant-garde. Gris’s pure Cubism links up with French tradition through Cézanne, who was the bridge between the twentieth century and a more distant past. Therefore, as Green points out, “ Bottle and Fruit Dish is a work which underlines the compatibility of Cubism and postwar tradition.”

Paloma Alarcó

Like other still lifes painted at Beaulieu-lès-Loches, Bottle and Fruit Dish exhibits an interplay of warm brown tones combined with colder greens and greys, taken directly from the landscape. Gris expressed his wish for the colour in his painting to rival the rich hues of nature in a letter to Léonce Rosenberg dated 10 August 1918: “In the countryside I see such solid and materially sumptuous tones and such perfect combinations, that they carry within themselves a far greater force than all the combinations of the palette, and I would like to work with them.” However, in contrast to these natural tones, the simple, flat geometry of the painting and the abstraction of the objects are clearly anti-naturalistic. The arrangement of the napkin that hangs over the edge of the table, a motif borrowed from Cézanne, has an interesting significance in the context of the so-called post-war “return to order” of the avant-garde. Gris’s pure Cubism links up with French tradition through Cézanne, who was the bridge between the twentieth century and a more distant past. Therefore, as Green points out, “ Bottle and Fruit Dish is a work which underlines the compatibility of Cubism and postwar tradition.”

Paloma Alarcó