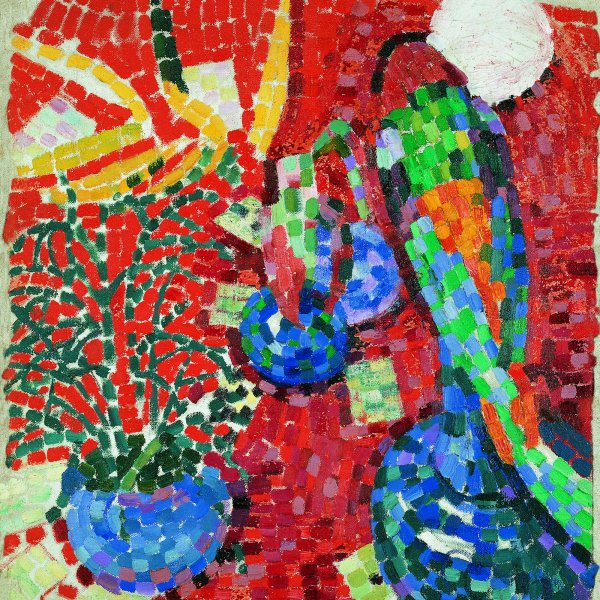

Woman with a Parasol

1913

Oil on canvas.

121 x 85 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

517

(1976.80

)

ROOM 42

Level 1

Permanent Collection

At the beginning of 1913 Robert Delaunay, who had enjoyed earlier success at various Salons in the French capital, travelled to Berlin with his poet friends Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars to take part in the Erster Deutscher Herbstsalon at the Der Sturm gallery. The work he showed at the exhibition, organised by Herwarth Walden, was a Woman with a Parasol combining Cubist fragmentation and superimposition of planes with the use of colour. It could be either the work in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza collection or another similar sized version of the same theme which belonged to the collection of Greta Garbo.

From 1912 onwards, the followers of the Cubist movement gradually evolved from their monochrome beginnings towards a more colourful mode. Robert Delaunay was one of the first to react against the chromatic monotony of analytical Cubism and to advocate “pure painting” and the importance of colour in painterly practice. The French painter, who left many writings on his own oeuvre and on his role as a pioneer of modern art, wrote in 1913: “Line is limitation. Colour gives depth (not perspective, not successive, but simultaneous) both its form and movement.” His colourful plastic language, with which he merged the principle of simultaneity of the Cubo-Futurists, which Delaunay was to term “simultaneous contrasts, ” was dubbed “Orphism, ” or “Orphic Cubism, ” by Apollinaire. This method of representing the rhythmic movement of an urban world through a new visual culture is based on a purely optical abstraction procedure that is a far cry from the spiritualist concerns of Kandinsky and Kupka, but close to Bergson’s notions of temporal continuity.

Although he is among the pioneers of abstraction, Delaunay never completely abandoned the visual perception of reality and exploited the possibilities of what he called “the simultaneity of vision.” By simultaneity of vision he meant the ability to move while viewing and, accordingly, the ability to view something in many directions, enabling us to perceive a whole host of aspects synchronically. “The relationship of vision with this ‘active space’, which is the real space of our perception, ” specifies Tomàs Llorens, “entails a sort of ubiquity, ” which Pascal Rousseau would call “vertigo of vision.” In this aspect Delaunay comes close to the retinal vision of Impressionism, of which the Cubists were so critical, and the ideas of the nineteenth-century colour theorist Eugène Chevreul. It should not be forgotten that Robert started out as an artist with an Impressionistic style and that the very title — Woman with a Parasol — brings to mind Impressionist paintings by Monet or Renoir, although there are even greater affinities with the female figures portrayed by the German Expressionist August Macke, with whom he enjoyed a close relationship after they first met in Paris in 1912. Lastly, it is impossible not to relate the colouring and geometrical pattern of the figure’s dress to Sonia, who dressed the modern woman in geometrical designs of coloured circles.

Paloma Alarcó

From 1912 onwards, the followers of the Cubist movement gradually evolved from their monochrome beginnings towards a more colourful mode. Robert Delaunay was one of the first to react against the chromatic monotony of analytical Cubism and to advocate “pure painting” and the importance of colour in painterly practice. The French painter, who left many writings on his own oeuvre and on his role as a pioneer of modern art, wrote in 1913: “Line is limitation. Colour gives depth (not perspective, not successive, but simultaneous) both its form and movement.” His colourful plastic language, with which he merged the principle of simultaneity of the Cubo-Futurists, which Delaunay was to term “simultaneous contrasts, ” was dubbed “Orphism, ” or “Orphic Cubism, ” by Apollinaire. This method of representing the rhythmic movement of an urban world through a new visual culture is based on a purely optical abstraction procedure that is a far cry from the spiritualist concerns of Kandinsky and Kupka, but close to Bergson’s notions of temporal continuity.

Although he is among the pioneers of abstraction, Delaunay never completely abandoned the visual perception of reality and exploited the possibilities of what he called “the simultaneity of vision.” By simultaneity of vision he meant the ability to move while viewing and, accordingly, the ability to view something in many directions, enabling us to perceive a whole host of aspects synchronically. “The relationship of vision with this ‘active space’, which is the real space of our perception, ” specifies Tomàs Llorens, “entails a sort of ubiquity, ” which Pascal Rousseau would call “vertigo of vision.” In this aspect Delaunay comes close to the retinal vision of Impressionism, of which the Cubists were so critical, and the ideas of the nineteenth-century colour theorist Eugène Chevreul. It should not be forgotten that Robert started out as an artist with an Impressionistic style and that the very title — Woman with a Parasol — brings to mind Impressionist paintings by Monet or Renoir, although there are even greater affinities with the female figures portrayed by the German Expressionist August Macke, with whom he enjoyed a close relationship after they first met in Paris in 1912. Lastly, it is impossible not to relate the colouring and geometrical pattern of the figure’s dress to Sonia, who dressed the modern woman in geometrical designs of coloured circles.

Paloma Alarcó