Merzbild Kijkduin

In the early 1920s Kurt Schwitters, one of the leading Dada artists, became interested in the new Constructivist, abstract idioms. This new Soviet art, in particular that of El Lissitsky, in addition to Schwitters’ contact with members of the De Stijl Neo-plasticist group (whom he met during a period in Holland in 1923), are reflected in works such as the present Merzbild Kijkduin.

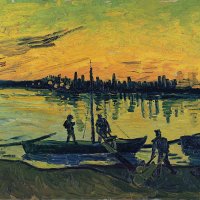

This Merz, an invented word that Schwitters gave to all his compositions, was created in Holland from objects found on the beach at Kijkduin. The element of chance intervenes to turn these random, throwaway objects into art and is used to break down artistic conventions. It establishes a dialogue with the artist’s desire to introduce the Constructivist aesthetic into a work in which flat planes and geometrical strips of colour prevail.

MRA

Schwitters attempted to reconcile Merz, his own particular brand of Dadaist anarchy, with the influence exerted on his work by the idealism of the new Constructivist abstract movements. Not only had he been marked by the geometric art of the Dutch De Stijl group and the Russian artist El Lissitzky, but the exhibition of contemporary Soviet art at the Van Diemen gallery in Berlin in autumn 1922 had had a powerful impact on him.

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Merzbild Kijkduin, an assemblage executed in Holland during the “Dada tour” Schwitters made with Theo and Petro van Doesburg and Vilmos Huszár in the early months of 1923, is one of the first examples of this change his work underwent. The word Kijkduin, included in the title of the present Merz construction, is the name of a village near The Hague. Despite the Constructivism that is evident in the arrangement of the composition, the use of materials found on the beach at Kijkduin — driftwood and other debris washed up by the tide — introduces the concept of chance that recalls the Dadaist works of his friend Hans Arp.

Schwitters achieves a perfect balance between the chaotic spirit of the found objects, characteristic of the Dada movement, and their geometric arrangement; between the somewhat unfinished and eroded appearance of the rough texture of the old bare wood and the uniformity of the painted surfaces; and between the two-dimensional effect of order created by the planar geometric shapes, forming squares and lines of colours, and the three-dimensionality of the relief of the objects employed in the construction, which are pasted or nailed on. In this world of contrasts that Merz epitomises, Schwitters “merzifies Constructivism” and attempts — successfully — to synthesise the two notions that are predominant in all twentieth-century art, order and chaos: “My aim is the total Merz art work, which combines all genres into an artistic unity.”

Until 1957 Merzbild Kijkduin belonged to the Dada artist Hannah Höch, who was among the few avant-garde members who did not emigrate with the advent of the Third Reich. She remained in her home on the outskirts of Berlin and concealed her entire collection inside a dried up well in her garden until the war ended in 1945.

Paloma Alarcó