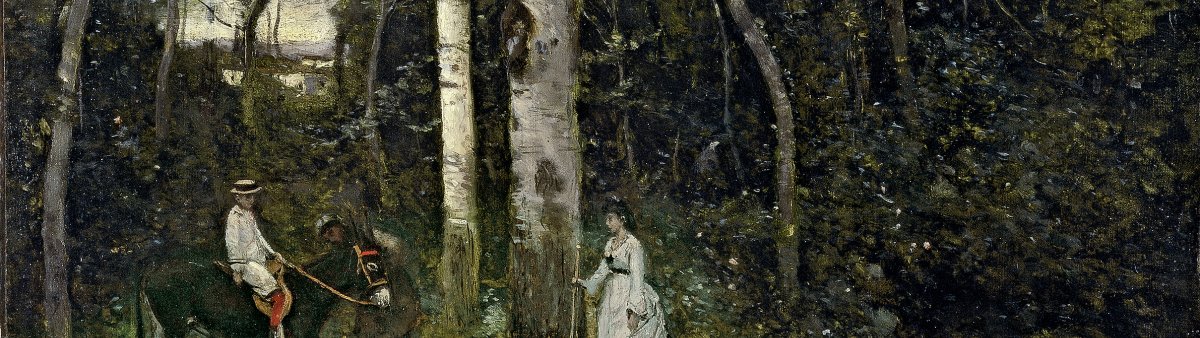

The Parc des Lions at Port-Marly

1872

Oil on canvas.

81 x 65 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

494

(1979.46

)

ROOM 33

Level 1

Permanent Collection

Camille Corot, whose art was halfway between Romanticism and Realism, preferred to paint a nature that inspired poetry and bucolic fantasy than to render it realistically as Courbet did. A pioneer of plein air painting, throughout his lifetime he attempted to capture the essence of nature, which earned him the admiration of the Impressionists, for whom he was a constant reference.

Located some twenty kilometres from Paris, Port-Marly — where Alfred Sisley later lived — is a village on the banks of the Seine, like Asnières, Argenteuil, Chatou, Louveciennes, Bougival and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which would very soon be made famous by the Impressionist painters. The Parc des Lions at Port-Marly, one of the most beautiful compositions from his final period, is an example of the artist’s landscape style. It was executed from life in August 1872 during a ten-day stay at the Château des Lions, owned by the Rodrigues-Henriques family since 1853. This mansion was inherited in 1857 by Georges Rodrigues-Henriques, a wealthy foreign-exchange and stock market agent, art collector and lover of painting, who became a diligent disciple of Corot during his mature years. In a small exhibition on this painting at the Museo Thyssen- Bornemisza, Ronald Pickvance studied the painter’s relationship with the family of his friend and disciple, to whom he gave the work in gratitude for his hospitality, and related it to other works by Corot, particularly Bacchanal at the Spring: Souvenir of Marly-le-Roi which was also owned by the Rodrigues-Henriques family. Although the settings were different — one is the parc des Lions and the other the forest of Marly-le-Roi — both works are the same size and were painted the same year, a fact which leads Pickvance to assume that Corot planned them as pendants.

In the painting in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Corot depicts an everyday scene in the park next to the castle featuring his host’s children, Valentine with a stick and Henri on a donkey. Two huge silver birches divide the composition into two halves and the dense undergrowth provides a protective wall, while also surrounding the clearing in the distance where what could be the outline of Saint- Germain-en-Laye can be distinguished. The composition is painted in a range of greens with a few hints of red on the boy’s smock and on the roofs in the background, while the execution, with light touches of colour that make the foliage vibrate, foreshadows the first steps towards Impressionism.

As in many of his sous bois paintings, Corot wishes to emphasise the smallness of man compared to the grandiosity of nature. As Germain Bazin points out, this work may recall the tiny figures found in Watteau’s compositions, barely sketched through a reflection of light. These evocative renderings of the depths of the forest, painted in a loose technique with luminous colours, make Corot the true initiator of modern landscape painting and earn him the title of “great father of French landscape painting.” One of his most fervent admirers, the painter Auguste Renoir, exclaimed in 1918, “There you have the greatest genius of the century, the greatest landscape artist who ever lived. He was called a poet. What a misnomer! He was a naturalist. I have studied ceaselessly without ever being able to approach his art.”

Paloma Alarcó

Located some twenty kilometres from Paris, Port-Marly — where Alfred Sisley later lived — is a village on the banks of the Seine, like Asnières, Argenteuil, Chatou, Louveciennes, Bougival and Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which would very soon be made famous by the Impressionist painters. The Parc des Lions at Port-Marly, one of the most beautiful compositions from his final period, is an example of the artist’s landscape style. It was executed from life in August 1872 during a ten-day stay at the Château des Lions, owned by the Rodrigues-Henriques family since 1853. This mansion was inherited in 1857 by Georges Rodrigues-Henriques, a wealthy foreign-exchange and stock market agent, art collector and lover of painting, who became a diligent disciple of Corot during his mature years. In a small exhibition on this painting at the Museo Thyssen- Bornemisza, Ronald Pickvance studied the painter’s relationship with the family of his friend and disciple, to whom he gave the work in gratitude for his hospitality, and related it to other works by Corot, particularly Bacchanal at the Spring: Souvenir of Marly-le-Roi which was also owned by the Rodrigues-Henriques family. Although the settings were different — one is the parc des Lions and the other the forest of Marly-le-Roi — both works are the same size and were painted the same year, a fact which leads Pickvance to assume that Corot planned them as pendants.

In the painting in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Corot depicts an everyday scene in the park next to the castle featuring his host’s children, Valentine with a stick and Henri on a donkey. Two huge silver birches divide the composition into two halves and the dense undergrowth provides a protective wall, while also surrounding the clearing in the distance where what could be the outline of Saint- Germain-en-Laye can be distinguished. The composition is painted in a range of greens with a few hints of red on the boy’s smock and on the roofs in the background, while the execution, with light touches of colour that make the foliage vibrate, foreshadows the first steps towards Impressionism.

As in many of his sous bois paintings, Corot wishes to emphasise the smallness of man compared to the grandiosity of nature. As Germain Bazin points out, this work may recall the tiny figures found in Watteau’s compositions, barely sketched through a reflection of light. These evocative renderings of the depths of the forest, painted in a loose technique with luminous colours, make Corot the true initiator of modern landscape painting and earn him the title of “great father of French landscape painting.” One of his most fervent admirers, the painter Auguste Renoir, exclaimed in 1918, “There you have the greatest genius of the century, the greatest landscape artist who ever lived. He was called a poet. What a misnomer! He was a naturalist. I have studied ceaselessly without ever being able to approach his art.”

Paloma Alarcó