Large Interior. Paddington

Although differing in method, Lucian Freud shares Francis Bacon’s interest in portraying the solitude of human existence through the same motif: the human body. Both artists, whose formative years were spent in the existentialist intellectual climate of interwar Europe, used their painting to reflect — fairly violently — on alienated, tormented mankind. However, whereas Bacon subjected his figures to a formal metamorphosis that left them battered and bruised, Freud always adhered to the traditional canons of the human body. In their studies the critics John Russell and Robert Hughes both describe him as the finest and only realist painter of the modern age, while Jean Clair, who hails him as one of the great artists, states that “with the exception of Picasso and Bacon, never before had the reality of the body been so harshly and so lovingly described, through the perverse means of distortion, in its beauty and its ugliness, in its strength and in its vulnerability, in its attraction and its repulsion, in its ceaseless and bitter search for individuality, expressed in a style which can be compared to the great styles of the past.”

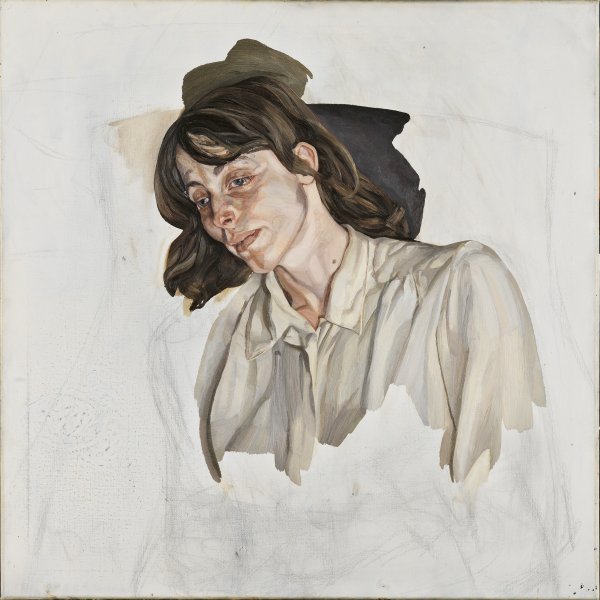

In this unsettling Large Interior. Paddington, executed in 1968‒69, Freud employs a cinematographic angle and upward perspective to depict a scene that unfolds inside his Gloucester Terrace studio in London. His daughter Ib (Isobel Boyt), wearing an expression of infinite sadness, lies semi-naked on the floor by a huge plant placed opposite a window. There is a small painting on canvas from the same period — entitled Small Interior. Self-Portrait— showing Freud with palette in hand, starting work on the present Large Interior, which depicts the scene reflected in a studio mirror.

To paint the present work, Freud was as meticulous as ever with the positioning of the easel in order to view the scene from a forced angle and capture it from a bird’s eye view. As William Feaver states, the houseplant with twisted branches that is given particular prominence here reminded the painter of a huge Zimmerlinde in his grandmother’s house. It is painted in the painstaking manner of his previous period and rendered in a different perspective to the window, which has an oddly disturbing effect on the viewer.

The semi-naked body of the girl on the floor, sheltered beneath the leaves of the plant, is in a pose that may appear natural at first sight, but when examined more carefully can be seen to be unnaturally twisted: the shoulders are parallel to the floor, while the hips and bent knees are turned partly to one side. Around 1965, when his painting had become looser and more impastoed, Freud began to paint nudes devoid of any idealism. Generally depicted in indoor settings, they provide both a physical and psychological vision of the sitter, as Freud intended the person’s expression to be fixed both in the body and in the face. Flesh has such a radical presence in these paintings that we even feel uncomfortable about looking at them. As John Russell aptly states, “Freud takes the experience so far that at times we ask ourselves if we have the right to be there.”

As in all his works, the palette is sober and totally naturalistic, as for Freud colour has only a representative, not an emotional value, and his range of colours has remained unchanged throughout his oeuvre. In his paintings emotion is created by forms and by impasto, not by colour. As he explained, “I don’t want colour to be noticeable. I want the colour to be the colour of life, so that you would notice it as being irregular if it changed. I don’t want it to operate in the modernist sense as colour, something independent.”

Paloma Alarcó