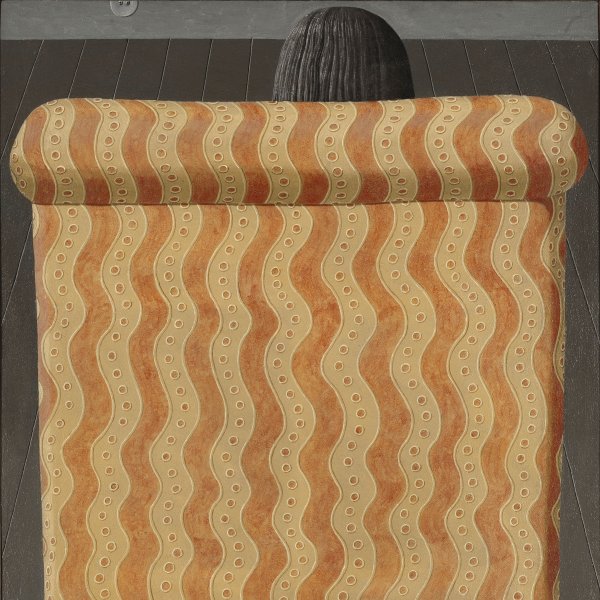

Portrait of a Woman [Rita] (?)

1965

Oil on canvas.

86 x 65 cm

Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid

Inv. no.

554

(1982.16

)

ROOM 49

Level 1

Permanent Collection

The painter and sculptor Alberto Giacometti belonged to a generation marked by the pessimism and anxiety of experiencing the crisis of two wars. This feeling took the form of existentialist thought, a new moral which, in the field of art, led creators to reflect — sometimes violently — on alienated, tormented mankind. Influenced by this existentialism, Giacometti contributed to shaping a new image of contemporary man through the new patterns of freedom of expression derived from both Expressionist gesture and Surrealist automatism. Jean-Paul Sartre himself considered Giacometti’s solitary figures to be a perfect translation into sculpture of his ideas on the loneliness and incoherence of the human condition.

Giacometti did not take up painting properly until returning to Paris in 1946. From his beginnings as a sculptor the human figure was an almost constant motif, and in the mid 1940s his interest in painting from life led him to produce portraits. The self-portraits of Rembrandt, the sad and sober Fayoum mummy portraits, together with the portraits by El Greco were his main references, and the people close to him, such as his brother Diego — with whom he shared his studio on the rue Hyppolyte-Maindron — his wife Annette, his friends David Sylvester, James Lord, Isaku Yanaihara and Jean Genet, and his lover, the Paris prostitute Caroline — were his most frequent sitters. One of his sitters, James Lord, an American writer living in France, wrote a detailed account of the long, silent sittings Giacometti subjected him to in order to paint his portrait. The French existentialist playwright Jean Genet posed for several portraits between 1954 and 1958, while working on L’Atelier, a story written as a diary, with a series of commentaries and notes on his conversations in the artist’s studio. According to Genet, Giacometti wished “to discover the secret pain within every person and even within every object, with the intention of illuminating them.”

The present Portrait of a Woman, painted in 1965, repeats the same pattern found in most of Giacometti’s portraits, in which the artist systematically dispenses with all narrative references. The half-length figure placed in the centre of the composition stares straight ahead in a hieratic pose, amid a space that surrounds her in such a way as to render her physical presence spiritual. The sitter has not been identified, as Giacometti’s faces ceased to be recognizable elements, and he transmits a mask-like inexpressiveness and silence that makes identity inaccessible. The figure has been eroded, deleted, reduced to the plastic expression of what the artist considered to be man’s existential condition in the modern age. The range of grey and ochre tones and the sketchy technique reinforce the feeling of the isolation of the figure, which conveys a powerful spirituality. The spatial structure, a sort of claustrophobic cage in which the figure is immobilised, is barely drawn in a brief sketch of the studio setting where the portrait is painted.

Jacques Dupin stressed that the changelessness of Giacometti’s life was matched by the imperturbability of his work: “He has occupied the same studio for thirty-five years, he frequents the same districts, the same cafés, and nothing has changed his way of life, however singular, deep down regular and almost ritual. Likewise, he does not intend to vary his subjects, diversify his models’ pose, the illumination of his works, the colours of his palette, and can shut himself away for a hundred nights in a row with the same sitter, work away at the same face for a hundred nights in a row.”

This immobility and hieratism, this aspiration to find an absolute plastic solution to the creation of an archetype, has sometimes led Giacometti’s evanescent figures to be compared to those Paul Cézanne painted of his wife Hortense. The changeless pattern of his portraits repeats, with slight variations, the equally inalterable composition of the numerous portrayals of Madame Cézanne, in which the master of Aix, in addition to eliminating any trace of spatial depth, portrays the sitter with a very powerful presence, but without expressive eloquence in order to render any kind of psychological interpretation impossible.

Paloma Alarcó

Giacometti did not take up painting properly until returning to Paris in 1946. From his beginnings as a sculptor the human figure was an almost constant motif, and in the mid 1940s his interest in painting from life led him to produce portraits. The self-portraits of Rembrandt, the sad and sober Fayoum mummy portraits, together with the portraits by El Greco were his main references, and the people close to him, such as his brother Diego — with whom he shared his studio on the rue Hyppolyte-Maindron — his wife Annette, his friends David Sylvester, James Lord, Isaku Yanaihara and Jean Genet, and his lover, the Paris prostitute Caroline — were his most frequent sitters. One of his sitters, James Lord, an American writer living in France, wrote a detailed account of the long, silent sittings Giacometti subjected him to in order to paint his portrait. The French existentialist playwright Jean Genet posed for several portraits between 1954 and 1958, while working on L’Atelier, a story written as a diary, with a series of commentaries and notes on his conversations in the artist’s studio. According to Genet, Giacometti wished “to discover the secret pain within every person and even within every object, with the intention of illuminating them.”

The present Portrait of a Woman, painted in 1965, repeats the same pattern found in most of Giacometti’s portraits, in which the artist systematically dispenses with all narrative references. The half-length figure placed in the centre of the composition stares straight ahead in a hieratic pose, amid a space that surrounds her in such a way as to render her physical presence spiritual. The sitter has not been identified, as Giacometti’s faces ceased to be recognizable elements, and he transmits a mask-like inexpressiveness and silence that makes identity inaccessible. The figure has been eroded, deleted, reduced to the plastic expression of what the artist considered to be man’s existential condition in the modern age. The range of grey and ochre tones and the sketchy technique reinforce the feeling of the isolation of the figure, which conveys a powerful spirituality. The spatial structure, a sort of claustrophobic cage in which the figure is immobilised, is barely drawn in a brief sketch of the studio setting where the portrait is painted.

Jacques Dupin stressed that the changelessness of Giacometti’s life was matched by the imperturbability of his work: “He has occupied the same studio for thirty-five years, he frequents the same districts, the same cafés, and nothing has changed his way of life, however singular, deep down regular and almost ritual. Likewise, he does not intend to vary his subjects, diversify his models’ pose, the illumination of his works, the colours of his palette, and can shut himself away for a hundred nights in a row with the same sitter, work away at the same face for a hundred nights in a row.”

This immobility and hieratism, this aspiration to find an absolute plastic solution to the creation of an archetype, has sometimes led Giacometti’s evanescent figures to be compared to those Paul Cézanne painted of his wife Hortense. The changeless pattern of his portraits repeats, with slight variations, the equally inalterable composition of the numerous portrayals of Madame Cézanne, in which the master of Aix, in addition to eliminating any trace of spatial depth, portrays the sitter with a very powerful presence, but without expressive eloquence in order to render any kind of psychological interpretation impossible.

Paloma Alarcó

![Portrait of a Woman [Rita] (?). Retrato de mujer [Rita] (?), 1965](/sites/default/files/styles/full_resolution/public/imagen/obras/1982.16_retrato-mujer-rita.jpg)