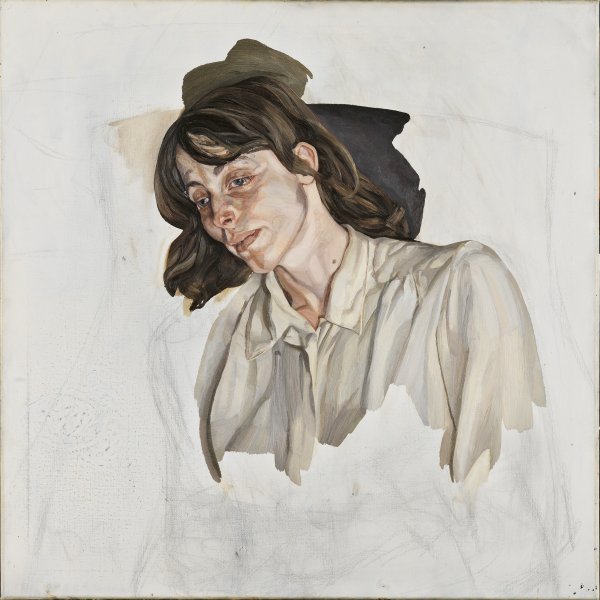

Portrait of a Man (Baron H.H. Thyssen-Bornemisza)

On 26 July 1981, Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza paid his first visit to the London studio of the painter Lucian Freud, near Notting Hill Gate, for the first of the long, endless sittings for the present portrait, which was completed in October 1982. This would be the start of a close and lasting relationship between painter and collector, which led them to discuss painting and compare their respective artistic tastes. It was an unforgettable experience for Baron Thyssen, who had never before posed as a sitter; and for the artist, a new source of inspiration for his subsequent oeuvre.

For nearly two years, Baron Thyssen punctually attended the sessions and Freud, who worked slowly and painstakingly, gradually progressed with the portrait. As on other occasions, Freud placed the sitter very close to his angle of vision, with a physical proximity that allowed him to spot the subtlest detail, the slightest gesture of the hands, the tiniest grimace or lock of hair out of place. With his concentrated, obsessive gaze, Freud always conducts a thorough examination of the sitter and achieves a psychological depth comparable only to that of Rembrandt or Goya’s portraits: “I try to enter as far as possible into their feelings, so the picture will be about them, not me.”

Freud returns to the portraits of heads that he had painted chiefly during the 1960s and shows the sitter slightly lower than shoulder length, dressed informally in a checked jacket, white shirt and dark tie. The frontal gaze and the introspection of his face recall the plaster portrait masks of Tel el-Amarna reproduced in Geschichte Aegyptens, Freud’s bedside book, to which so many references are found in his painting from 1939, the year it was given to him by his friend and patron Peter Watson. Freud, who never makes preliminary drawings, began working directly on the canvas. The portrait progressed from the first freehand sketch in charcoal and the first touches of oil, and was gradually completed with pentimenti and superimposed brushstrokes alongside layers applied with a palette knife. In the end the painted portrait speaks as much of the sitter as it does of the painter’s frenzied attempt to portray him.

As a backdrop, barely sketched above the sitter’s right shoulder, Freud inserts a fragment of Antoine Watteau’s Pierrot Content, of circa 1712, belonging to the baron’s collection since 1977, a reproduction of which he pinned to a wall of his studio. Interestingly, in Freud’s portrait the baron is positioned in the spot occupied by Pierrot in Watteau’s painting; one even has the impression that he adopts the same pose and expression. The position of his head, slightly tilted forwards, and his downward gaze make the magnate more gloomy and mysterious and distance him somewhat from the viewer.

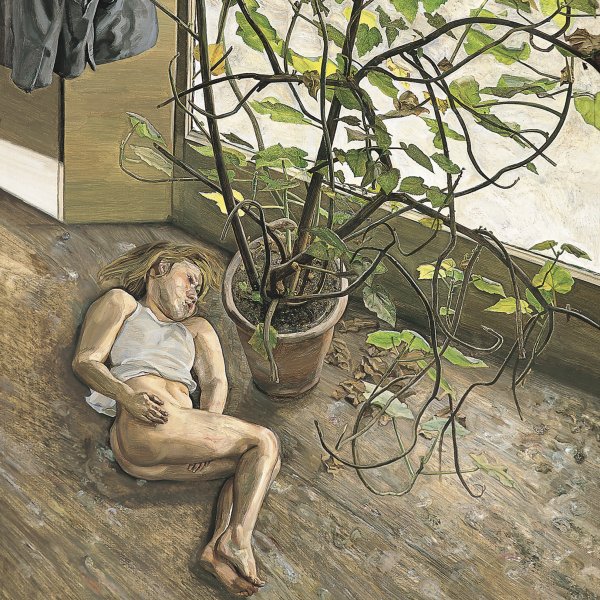

A whole host of allusions to Great Masters from Egyptian art to Grünewald, Hals, Velázquez, Rembrandt, Daumier, Watteau, Géricault, Ingres, Courbet, Rodin and Bonnard can be found in the oeuvre of Freud, a great admirer of the art of the past, although this close link with painting tradition is combined with a keen desire to be independent from it. Pierrot Content caused such an impression on Freud that he decided to make a pastel copy of the painting, repeating the poses and clothing of the figures almost exactly, although he changed their facial features. Shortly afterwards, still under the magical influence of this work, he put his mind to painting a picture paraphrasing Watteau’s small work, which resulted in one of his most ambitious paintings: Large Interior W 11 (After Watteau), a group portrait of several of his relatives and friends, which he worked on industriously between 1981 and 1983. Although he adopted the same composition as Watteau’s work, he gave it a completely different twist. With his personal mise-en-scène and manner of penetrating the inner world of several of the people close to him, Freud transformed a theatrical theme on human feelings, characteristic of the commedia dell’arte, into an interpretation of his own private life and converted Watteau’s fantasy into an unquestionably modern theme.

Paloma Alarcó