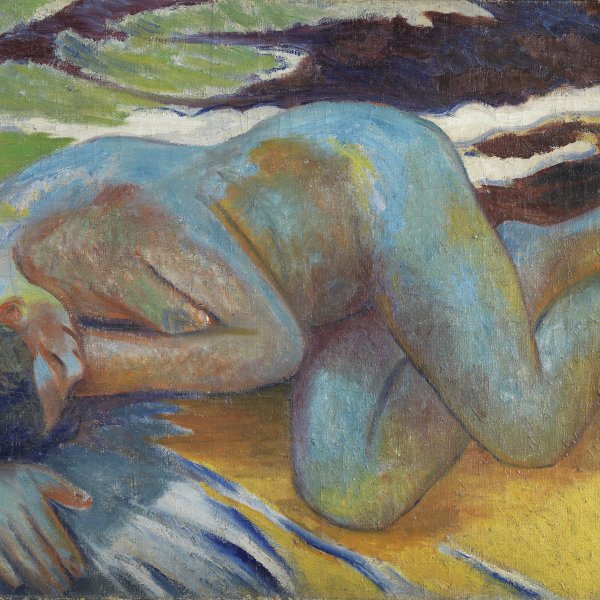

Fishing (fishers)

1909

Oil on canvas.

112 x 99.7 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.1977.34

)

ROOM H

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

Goncharova, chronologically the primary woman artist of 20th-century Russia, both cultivated an intellectual interest in the traditional handicrafts and primitive rituals of old Russia and also used them as subjects for her pictures and designs. Naturally, Goncharova's attitude influenced the formal arrangements of her painting, contributing to the intense stylisation, forceful colour combinations and naive perspectives and proportions that we recognise in Fishing. Goncharova observed the peasants firsthand during her frequent trips to the family country home at Polotnianyi Zavod near Moscow and that they became a major part of her artistic vocabulary is clear from Fishing and similar explorations of the "primitive" such as Washing Linen (1910) and Peasants Picking Apples (1911) (both Tretiakov Gallery, Moscow). Goncharova's study of Russian peasant costume and ornament also prepared the way for her folkloristic evocations in Diaghilev's Paris productions of Le Coq d'Or (1914) and L'Oiseau de Feu (1926) as well as for her book illustrations to Kruchenykh's Pustynniki [Hermits] (1913) or to the Paris edition of the Conte de Tsar Saltan (1922). This recognition of the vitality and potential of traditional Russian art forms also prompted her and Larionov to organise an exhibition of "Icons and Broadsheets" in Moscow in 1913.

Fishing is direct evidence of Goncharova's own response to, and reordering of, certain conjunctions and devices of "traditional" art in her search for experimental pictorial resolutions. Of course, in the context of the Russian avant-garde, the term "primitive" must be used in a broad sense, for it covers not only cultural manifestations of "primitive" peoples (pre-Christian Russians, the Scythians, the Siberian nomads, the Russian peasantry), but also the canons of mediaeval Russian culture, especially icon-painting, as well as the urban folklore of the 19th and 20th centuries. In the bright colours, emphatic lines, intense stylisation, and general optimism of Russian peasant art, Goncharova found a vigour and integrity that seemed to be lacking in contemporary bourgeois culture. Goncharova and her immediate colleagues such as Larionov, Malevich, Shevchenko (who published the Neo-Primitivist manifesto in 1913) and Tatlin regarded the traditional arts and crafts as a decisive element in the renovation of Russian art and design, even arguing that Russia was part of Asia and that the East was the real birthplace of all modern art. Of course, Goncharova also studied contemporary Western models including post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Futurism, and the combined influences of Gauguin and Matisse, for example, are manifest in the colouring and decorative flatness of Fishing. In other words, Goncharova was able to borrow Western forms and reprocess them within the indigenous environment, a procedure that often involved a sudden shift of aesthetic registers from "high" to "low". Moreover as Goncharova affirmed in a speech that she gave in Moscow in 1912, she did not hesitate to give preference for the domestic over the imported: "Cubism is a positive phenomenon, but it is not altogether new. The Scythian stone images, the painted wooden dolls sold at fairs are those same Cubist works".

John E. Bowlt y Nicoletta Misler

Fishing is direct evidence of Goncharova's own response to, and reordering of, certain conjunctions and devices of "traditional" art in her search for experimental pictorial resolutions. Of course, in the context of the Russian avant-garde, the term "primitive" must be used in a broad sense, for it covers not only cultural manifestations of "primitive" peoples (pre-Christian Russians, the Scythians, the Siberian nomads, the Russian peasantry), but also the canons of mediaeval Russian culture, especially icon-painting, as well as the urban folklore of the 19th and 20th centuries. In the bright colours, emphatic lines, intense stylisation, and general optimism of Russian peasant art, Goncharova found a vigour and integrity that seemed to be lacking in contemporary bourgeois culture. Goncharova and her immediate colleagues such as Larionov, Malevich, Shevchenko (who published the Neo-Primitivist manifesto in 1913) and Tatlin regarded the traditional arts and crafts as a decisive element in the renovation of Russian art and design, even arguing that Russia was part of Asia and that the East was the real birthplace of all modern art. Of course, Goncharova also studied contemporary Western models including post-Impressionism, Cubism, and Futurism, and the combined influences of Gauguin and Matisse, for example, are manifest in the colouring and decorative flatness of Fishing. In other words, Goncharova was able to borrow Western forms and reprocess them within the indigenous environment, a procedure that often involved a sudden shift of aesthetic registers from "high" to "low". Moreover as Goncharova affirmed in a speech that she gave in Moscow in 1912, she did not hesitate to give preference for the domestic over the imported: "Cubism is a positive phenomenon, but it is not altogether new. The Scythian stone images, the painted wooden dolls sold at fairs are those same Cubist works".

John E. Bowlt y Nicoletta Misler