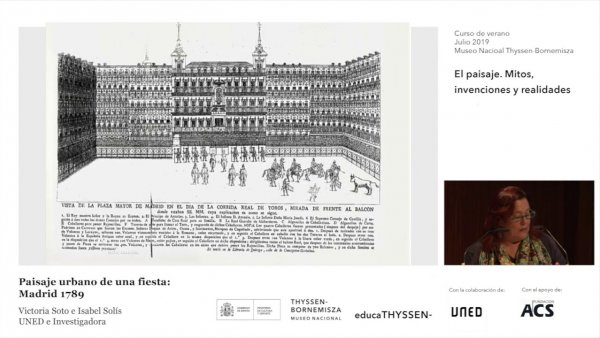

View of the Carrera de San Jerónimo and Paseo del Prado with a Procession of Carriages

Neither the exact subject-matter nor the authorship of this painting have yet been firmly decided, as Ángel Aterido has previously noted elsewhere, however, it yields a great deal of extremely interesting information. Perhaps the most important element is the actual site depicted, which is the meeting point between the Carrera de San Jerónimo and the Paseo del Prado Viejo de San Jerónimo, the spot where the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum is now located. The place is depicted as it would have appeared in the last years of the Habsburg dynasty during the reign of Charles II, a dating that can be deduced from the dress of the figures. This painting is not the only one of this location in Madrid, as there is another in the collection of the Marquise of Santa Cruz dating from the early decades of the 17th century (judging from the clothes of the figures and the technique), however, that work is basically a view of the Carrera de San Jerónimo from the Paseo del Prado while the Paseo itself is only represented by the foliage of some trees near the crossing of the two streets. This is possibly the painting mentioned by Mesonero Romanos as in the collection of the Marquis of Salamanca.

The present work is an outstanding representation of the Madrid known to the Countess d`'Aulnoy, who, during her visit to the capital in 1679, spoke of rather wide streets but noted that "there are no streets worse in the world [...] and the horses always have wet feet". Madrid was a city choked with carriages, the roads impassible due to the mud in winter and dusty in the summer, according to its chroniclers. The area around the Carrera de San Jerónimo became important after the construction of the Buen Retiro Palace in the 1630s, while the Paseo del Prado, although not yet built up, was a shady, tree-lined area which had been used as a pleasure route for the carriages of the city's upper classes since the second half of the 16th century. López de Hoyos describes the entry into Madrid of Ana of Austria in 1570 along this route which, during the time of the construction of the Buen Retiro, had three rows of trees, four small fountains and a small tower known as the "tower of music" as it housed musicians whose music made the Paseo agreeable.

The Carrera de San Jerónimo as depicted in the present work includes a modest group of buildings which includes the simple, and apparently unfinished, convento de clérigos menores del Espíritu Santo. This institution was established by the Caballero de Gracia in the late 16th century in the street which now bears its name, but due to various problems it moved to its new home built under the sponsorship of the Marquise del Valle. Work on the church was finished in 1684, a fact which will help to date the present painting, given that it does not include the two towers which decorated its façade and which we know from early 19th-century prints. This building was destroyed by fire in 1823, possibly intentionally, as it took place while the Duke of Angoulême and some of his officers from the Hundred Thousand Knights of St. Louis were present at a mass. The state of the building was so ruinous that the monks moved out and the site was later occupied by the Lower House of Parliament.

In the lower left corner we can just make out the building which was the pleasure palace of the Duke of Lerma and which was partly built by Juan Gómez de Mora. Don Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas was the first important court figure to consider the Prado Viejo de San Jerónimo as a suitable site for a suburban villa, and following his death this property passed through family inheritance to the Dukes of Medinaceli, to whom it belonged until 1895.

At the beginning of the 17th century the plots of land on either side of the Paseo del Prado were divided into small parcels of land belonging to numerous, anonymous owners. The plot on which the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum now stands belonged in 1613 to the Count of Villalonga. When part of it was expropriated from him to regularise the layout of the Paseo, he sold the estate to various buyers who turned the land over to the fruit and vegetable gardens which were the norm in this area.

After the building of the Buen Retiro Palace, the land became more valuable and was given over to different use. The aristocracy, wishing to be near the monarch, bought a large number of small plots in order to build noble houses, a process which eventually meant that the land passed into the hands of a few owners. In 1663 the plot now occupied by the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum was almost entirely owned by Don Diego de la Cerda y Silva, Count of Gálvez, who purchased from the Duke of Maceda a vegetable garden next to his land, located off-street and without access to the Paseo del Prado. This is the only information available up to now regarding the properties of the Duke of Maceda in this part of Madrid, although there is an old tradition in the literature of one of his properties being on this corner, information which has not been confirmed by any document to date. In the 1670s the plot passed into the hands of Doña Francisca Manrique Lara, who left it to her brother the Count of Frigiliana. His descendents sold it to the Duchess of Atri in 1736, while the Duke of Villahermosa owned it from 1771, and built the palace which now occupies the site. The building work evident in the present painting may be the construction of the home of the Count of Gálvez, who seems to have been the first to own a house in this location. From this point and looking towards the end of the Paseo in the painting we can make out a succession of fruit and vegetable plots and gardens, reaching to the Huerta de Juan Fernández, located at the entrance to the Prado de Recoletos in the present Plaza de Cibeles. This was a famous spot for picnics and festivals and was a key element in Madrid social life in the 17th century, also giving its name to a comedy by Tirso de Molina. The right side of the Paseo de Prado Viejo de San Jerónimo, barely visible in the painting, was an area which bordered the plot occupied by the Buen Retiro Palace.

Equally as interesting as this architectural and urbanistic aspect is the identification of the person and the event represented in the painting. This, however, proves difficult due to the lack of specific coats-of-arms or badges of office on the carriages in the procession. The characters taking part are undoubtedly making their way to the Buen Retiro Palace in order to extend some courtesy to the monarch. The protagonist must be an important figure from the number and richness of the carriages, all of which are drawn by four horses, which the sumptuary laws only permitted for princes, ambassadors, members of the aristocracy, etc. It has been suggested that the protagonist is Prince Eugene of Savoy-Carignan, who visited Madrid in 1686 accompanied by his mother Olimpia Mancini, Countess of Soissons. While the Savoy were a family particularly highly esteemed by the later Spanish Habsburgs as they were descendents of Philip II's daughter, Catalina Micaela, the personal situation of the illustrious visitors at that time does not make it likely that they could have made an entry into the city or presentation at court of the type seen here, since these ceremonies were paid for by the protagonists themselves. The Countess of Soissons had arrived in Madrid from Brussels where she had lived for the past few years in exile from Louis xiv, her bitter enemy.

Thus, it seems prudent to discard the identification with Eugene of Savoy and change the identification to an as yet unknown dignitary, whose identity may be revealed by further research. We would also suggest dating the painting to the last years of the 1670s, due to the clothing and hairstyles of the figures which are very close to those of the period of Maria Luisa de Orléans. This dating would also coincide with information given earlier on the Carrera de San Jerónimo, in which the Convent of the Holy Spirit is as yet incomplete at the end of the 1670s, therefore explaining the lack of the towers of the façade in the painting, as mentioned above.

Just as it is difficult to specify the exact subject of the painting, so it is to identify the artist, as this is a rare subject in Spanish art of this period. The painting has been attributed to the Antwerp-born, Madrid-based artist Jan van Kessel III, probably because he was trained in a school more familiar with this genre. There are very few works which can be securely attributed to him, and for this reason we need to wait for the appearance of other, similar works in order to be able securely identify the artist of this painting. It may in fact be by a Spanish artist, as other views of cities and of ceremonies are known from this period, which suggests the production of such works by artists in Madrid.

Trinidad de Antonio