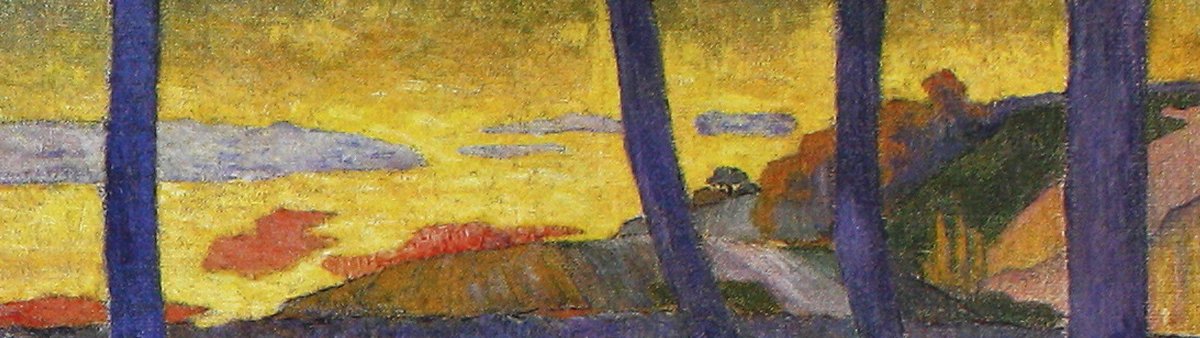

Lilacs

1885

Oil on canvas.

34.9 x 27 cm

Carmen Thyssen Collection

Inv. no. (

CTB.2000.4

)

ROOM F

Level 0

Carmen Thyssen Collection and Temporary exhibition rooms

The year 1885 was a critical one for Gauguin, both for his personal life and the direction of his art. During the first months of that year, he lived with his family in Copenhagen, his wife Mette's native city. Although Gauguin was registered in the town census as a travelling salesman, he was increasingly devoting his time to painting and through the Society of the Friends of Art of the Danish capital he was able to exhibit and even sell some works. He also wrote some Synthetic Notes which reveal Neo-Romantic sensibilities (for example, in his repeated comparison between painting and music) and a clear intention to go beyond the ideas of Impressionism. In June, after a heated argument with his wife's parents, Gauguin set out for Paris, taking with him one of his children, his young son Clovis. Eventually, this separation from his wife became permanent. In Paris, Gauguin experienced serious economic difficulties that he tried to resolve by asking Durand-Ruel to buy back a Renoir and a Monet from his own collection. We know that during the month of June he lived in the house of his friend Schuffenecker and his family, at number 29 of rue Bolard. It was at this point that he painted this Vase of Flowers.

The choice of objects for this still-life-the Neo-Classical vase of porcelain with a mythological figure, the flowers, the coloured shawl and the half-hidden book-suggest a refined, albeit slightly conventional taste. The design is more naturalistic and less simplified than in other still-lifes painted in the same period, such as the Still-life with a Vase of Japanese Peonies and a Mandolin (Paris, Musée d'Orsay). Compared to other works of the same period, the present composition has a fresher, less abstract character and a spontaneity that is more impressionistic. Such features are undoubtedly due to the fact that, more than a painting, it is a life-size study, evident in its small format.

Particularly notable is the dense texture of the paint in the background, achieved through the use of parallel strokes. This is a technique derived from Cézanne, whom Gauguin met in the circle of Pissarro. The sombre and dramatic harmony of the colours, based on the contrast between the light and luminous touches of the flower and the greens and dark blues of the background, is also comparable to the dark Romanticism of Cézanne's early work. In a famous letter to Schuffenecker, written in Copenhagen just a few weeks earlier, Gauguin evoked the example of Cézanne, in whose painting "the colour is grave like the character of the Orientals."

Guillermo Solana

The choice of objects for this still-life-the Neo-Classical vase of porcelain with a mythological figure, the flowers, the coloured shawl and the half-hidden book-suggest a refined, albeit slightly conventional taste. The design is more naturalistic and less simplified than in other still-lifes painted in the same period, such as the Still-life with a Vase of Japanese Peonies and a Mandolin (Paris, Musée d'Orsay). Compared to other works of the same period, the present composition has a fresher, less abstract character and a spontaneity that is more impressionistic. Such features are undoubtedly due to the fact that, more than a painting, it is a life-size study, evident in its small format.

Particularly notable is the dense texture of the paint in the background, achieved through the use of parallel strokes. This is a technique derived from Cézanne, whom Gauguin met in the circle of Pissarro. The sombre and dramatic harmony of the colours, based on the contrast between the light and luminous touches of the flower and the greens and dark blues of the background, is also comparable to the dark Romanticism of Cézanne's early work. In a famous letter to Schuffenecker, written in Copenhagen just a few weeks earlier, Gauguin evoked the example of Cézanne, in whose painting "the colour is grave like the character of the Orientals."

Guillermo Solana