Hyperrealism in the Blanca and Borja Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

Continuing with the family tradition, Blanca and Borja Thyssen-Bornemisza have been art lovers for many years, with a particular passion for modern and contemporary painting which until now they have collected in a very discreet fashion, away from the public gaze. This year, coinciding with the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza’s 30th anniversary, the couple have decided to present their collection to the public at the museum, of which Borja Thyssen is a member of the Board of Trustees. Blanca and Borja have consulted the museum with regard to their recent acquisitions, some of which are already on display in the galleries. These range from a splendid Cubist still life by María Blanchard (1918), a canvas by Francis Picabia from his “Transparencies” series (1925-27), a self-portrait by Richard Estes set in New York’s “ground zero” (2017), and a large-format painting by Julian Opie (2014). In conjunction with the exhibition on Alex Katz held at the museum last year, Blanca and Borja acquired a large canvas by the artist (Vivien, 2016), which had been previously selected for inclusion in that exhibition and which will soon be on display in the galleries.

While the habitual museum practice is to exhibit completed collections, Blanca and Borja Thyssen’s support is making it possible to show visitors “how an art collection is formed” as an ongoing activity. For this reason, the Museo Thyssen is now launching a series of exhibitions which will present the continuing process of the creation of the couple’s contemporary art collection. Opening on 3 October, the first edition in this series will display a small selection of eight Hyperrealist paintings.

The Hyperrealism movement emerged in the United States in the 1960s as a derivation of Pop Art and was termed “Photorealism” by the gallerist Louis K. Meisel. Based on the painted reproduction of photographic originals, Hyperrealism also looks back to the major precedents in art history. Landscapes, often panoramic views of cities or suburban locations, connect with the 18th-century Italian tradition of vedute painting. With regard to still life, the principal references are 17th-century Dutch examples and late 19th-century American trompe l’oeil painting.

The present exhibition opens with two views of New York by Richard Estes (born 1932), the most iconic representative of American Hyperrealism and the subject of an exhibition at the museum in 2007: People’s Flowers, 1971, which is a more classic view, and Self-portrait near the Oculus at World Trade Center, 2017, a more recent one. Like Estes, Charles Bell (1935-1995) belonged to the first generation of the movement. Bell’s still lifes nostalgically evoke the world of his childhood, with a particular fondness for depictions of old tin toys, marbles, chewing gum vending machines and pinball machines, as seen in the work on display (Tropical Nights, 1991). A leading member of the second generation of American Photorealism, Don Jacot (1949-2021) became known in the 1980s for his depictions of his native Chicago, after which, and like Bell, he turned to painting still lifes featuring vintage toys before returning to views at the end of his career, including the example now on display, 49th and Broadway (2019).

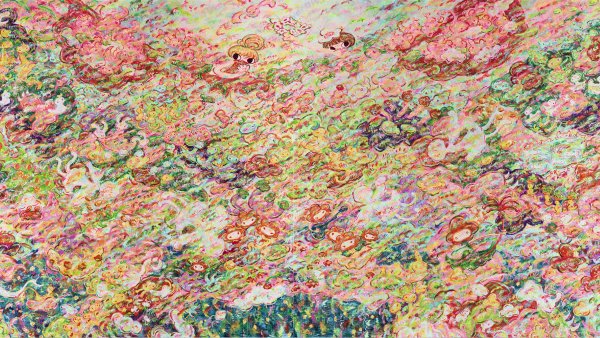

Bertrand Meniel (born 1961), Roberto Bernardi (born 1974) and Raphaella Spence (born 1978) represent more recent generations of Hyperrealism, which had become a completely international movement. Meniel focused on the urban landscape and Lucky Dragon (2009) depicts a corner of Chinatown in San Francisco in a scene that combines an everyday, familiar picturesqueness (the Chinese shop) with a recognisable landmark (the Transamerica Pyramid in the background). Bernardi specialises in dazzling, colourful still lifes with glass objects and sweets, as in Bunny in the Corner of 2019. Raphaella Spence’s two paintings move away from habitual themes within the Hyperrealist repertoire to show us the exuberant vitality of nature (The Path, 2019) and the alarming degradation of the environment (Schweppes, 2022).