IKEA and the art of home. Design for a better everyday life

A home is much more than the place where we live. It is a reflection of those who live in it and of the society to which we belong. It bears witness to the changes we have experienced over time, from our personal relationships to the way we understand the public, the private and our intimacy. It also shows how design and technology have evolved to adapt to the needs of a constantly changing population.

This tour of the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection invites us to discover how the spaces we call home have shaped our lives throughout history. For in every corner of a home and in the art forms that surround us, we find stories that tell us of that profound connection between the design of the home and the changing pace of the world in which we live.

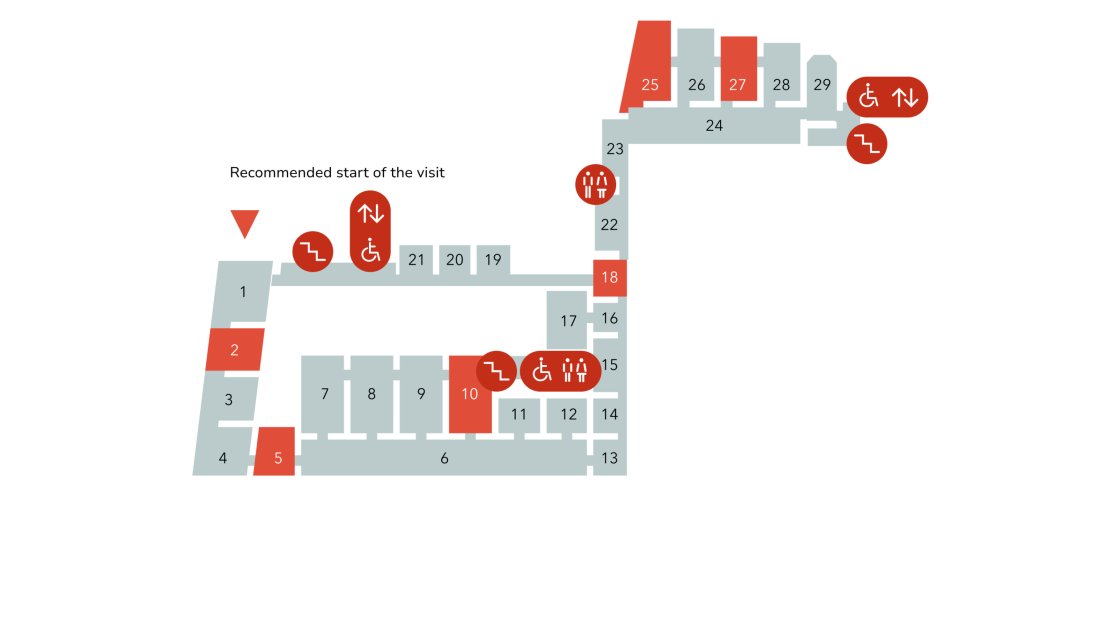

Artworks on the second floor

The itinerary begins through centuries 15th to 18th

Gabriel Mälesskircher

Saint Matthew the Evangelist

Room 2

The descriptive nature of this piece portrays a late medieval studio-workshop that depicts the artisanal production of a book. The printing press had been invented 25 years earlier, but scribes and copyists were still active, so the artist sets out to highlight their professional standing by depicting them with such care and attention to detail as to reflect his own craft (Gabriel Mälesskircher had previously trained as a miniaturist of books in his youth).

This space is arguably more inspired by the private workshop of a lay scribe than by the austere scriptoria found in monasteries, representing the place in the house where he carries out his work while also incorporating necessary elements of his personal life during his long days.

The background features a hanging towel and a fixed washbasin with a water tank: washing hands was essential for clean work and hygiene at a time when people used their hands to eat. Next, we see a brush and a cavity with a shelf that would have been used to transfer objects from one room to another, an element that features in other works by the artist. The sturdy cupboard, with its metal hardware and gothic decor embodying the essential nature of carpentry and ironwork, could be used to store books and other objects out of reach from rats or to hide away a stove. Above all these elements is a shelf adorned with bowls for eating and jugs for drinking. These are a popular type of lidded jug from Northern Europe that place the work in a certain milieu.

The diverse uses for this space are thus expressed through the furniture and objects, which serve to unite the professional and private life. This versatility continues through the furniture, such as the table, which holds tools for creating codices and sacred objects, but which could also serve as a desk if its lid were closed, or as somewhere to arrange books. At that time, the most valuable volumes were positioned horizontally on tables and shelves, while the rest were kept in chests, cupboards or in lockable tables like this one. There is a strong functional component in furniture from the medieval period, which, together with simple forms and minimalist style, attempts to meet many needs in one single piece, achieving the first examples of multifunctional furniture. One such example is the chest that could be used for storage, as a seat, table or step, and even a bed. However, despite the simplicity of medieval furniture, it offers intelligent solutions that are impressive even by today’s standards thanks to its versatility. Given the importance of religious furniture, some of the most interesting pieces are found in the monastic sphere. What’s more, its durability is ensured by its almost architectural, solid and robust nature, meaning that some of these pieces have survived to this day.

Domenico Ghirlandaio

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni

Room 5

This portrait by Ghirlandaio evokes the values of classicism: harmony, balance, proportion, elegance... Every element of Giovanna Tornabuoni’s figure seems to have been perfectly measured and nothing is superfluous. The few elements of architecture and furniture that can be seen in the work also embody these characteristics, echoing the subject, adding horizontality, straight and refined lines, and a sense of symmetry.

The values of classicism, in their historical context, transcend the Renaissance era and the Italian sphere. These values are often recaptured to correct what are considered stylistic excesses, straightening lines and simplifying ornamental elements. In spheres prone to decorative sobriety and pragmatism (Anglo-Saxon, Dutch, Scandinavian, etc.), they remain a formal bastion that never fully dissipates. Their historical prestige dates back to ancient times and makes them an ideal of beauty with which to engage in dialogue.

In the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance, the sparse furnishing found in homes and palaces becomes more elaborate, resulting in a first golden age of cabinetmaking. The simple, robust furniture of the Medieval period evolves towards lighter, more sophisticated pieces, while other generic and multi-purpose pieces such as the chest―although still in use (like the Italian cassone)―give way to more specific types and compositions based on panels and mouldings that accentuate symmetry.

The honing of furniture-making techniques had been ongoing since the 13th century. The hydraulic saw made it possible to obtain boards and work with panels, while the use of tongue and groove joints, secured with dowels, gave the furniture a better finish. Work began with a frame of upright posts and crossbeams as a basis, which was then covered with lighter panels, assembled piece-by-piece. In contrast to the earlier predominance of walnut and oak, new materials, finer and more exotic woods, as well as finishing lacquers and varnishes also began to be used. Marquetry emerged in Italian Medici workshops in Siena and Florence, reaching a virtuosic level of skill in the fascinating studioli of noble humanists in Urbino and Mantua. More and more works began to emerge that are considered “non-standard” because their material quality and workmanship transcend the carpenter’s guild trade. Finally, the introduction of sketches for furniture design ultimately expressed the artistic consideration that began to be attributed in this period to the work of producing furniture pieces.

Hans Memling

Flowers in a Jug (verso)

Room 5

By painting the reverse of this work, Memling created one of the first still life paintings on panel in the Western pictorial tradition, a genre with an evident decorative meaning, much like that given to vases displayed in homes today. This piece highlights the decorative function of objects, as does the rich oriental tablecloth, and the importance that introducing nature into homes acquires in this sense. Beauty and nature are incorporated as dimensions in the way the home is defined.

The objects depicted in the work incorporate a symbolic value that is also linked to social standing, expressing a certain status. The tablecloth also highlights the active trade with the East for whose products Venice was a gateway, a taste for objects brought from distant lands that allowed a select few to introduce exoticism into the home, something that would have a long history in the European cultural sphere, increasing with the rise of global trade. The depiction of tablecloths or rugs would become popular in Europe thanks to their inclusion in Flemish Renaissance works such as this one. They are, in fact, known as “Memling rugs” (just as those depicted by Holbein would adopt the name “Holbein rugs”). The complex decorative tapestries reflected the technical skill of the artist, who claimed fees accordingly.

The chrismon featured on the jug and the flowers themselves depict another form of symbolism, linked in this case to Christianity, to the sacred. The faithful identify these objects as such and they also point to an identity linked to these beliefs. The layers of meaning and value associated with objects always go beyond mere appearances, not only in paintings, but in homes themselves.

Jan de Beer

The Birth of the Virgin

Room 10

This birth scene of the Virgin, depicted as an everyday, bourgeois scene from the 16th century, portrays life revolving around the bed, because for a long time most houses consisted of a single room and a large part of domestic life took place around this piece of furniture. Even with more rooms, there was still no defined notion of privacy, something that would become key in separating off the bedroom and in differentiating private and social spaces within the home. A glimpse of this begins to emerge in rich, bourgeois homes like the one depicted here, although, as is also apparent, the bedroom is the site of numerous activities that make it the centre of the house, the place where the most significant aspects of life unfold: here one is born and dies, one rests, becomes intimate, eats, receives visitors, plays... Some elements of this painting are suggestive of the bathroom, such as the towels, the niche-sink in the background or the ewer with a basin in the foreground. Other elements evoke activities that could lie somewhere between the recreational and the professional, such as sewing (the items in the basket are also used in childbirth). As this is the main room, it contains the fireplace―the epitome of home―with a cauldron over the fire, from which the woman may have taken the broth she is serving, a bowl of milk, two round stones to warm beds and what appears to be part of a frying pan. One of the biggest challenges in the evolution of domestic spaces would be how to keep them warm, and tall, deep fireplaces, like the one in this work, were not an especially effective means of achieving this.

The bedroom’s multitude of uses is expressed in the concentration of objects and furniture, representative of a certain social standing and a plethora of trades that work with such diverse materials, brought together in guilds that regulate and consolidate the decorative arts. Worthy of note here―as it is an object still considered unusual in homes of that time―is the small convex mirror hanging from the window, as well as a unique detail to its right: the wing of an angel lends the whole piece a sacred meaning.

Textiles play a prominent role in this work, in keeping with their provenance, Flanders, with its unrivalled, rich textile industry. In an era in which furniture lacks comfort, textiles, such as the cushions seen on the bench or the bed, are used to improve this. Blankets and canopies (hung here from the ceiling, as was the fashion) worked to insulate from the cold and it was common to spread cloths, enriched with embroidery, hemstitching and fringes, over furniture as a decorative flourish, as can be seen in this painting. Bedrooms were decorated through textiles more than through furniture. White clothing, which was scarce and expensive until the 16th century, became more common with the refinement of linen cloth, which was also used to make sheets.

The bed takes centre stage and is highlighted by the headboard and canopy. It is raised according to an ancient custom that distinguishes its hierarchy and protects it from humidity and rodents. It is the most precious piece of furniture in the house and also the most comfortable, which is why guests are received there and why the best bed is offered to them as a sign of hospitality. There are large beds for the whole family to sleep in, not only out of necessity (a single bed and room, protection from the cold, etc.) but also out of habit. Some look like wardrobes, creating the illusion of a room within a room to maximise space, combat the cold and offer privacy as needed, using canopies for example. They would make up a significant part of the assets of the poorest people (where they owned them) and would be worth an awful lot of money for the richest, who sometimes collected them or even took their most prized bed with them. One such example that will go down in history is the “second-best bed” that Shakespeare bequeathed to his wife in his will.

Pompeo Batoni

Portrait of the Countess Maria Benedetta di San Martino

Room 18

The Countess painted by Batoni belongs to an era that was already coming to an end. France was on the verge of a revolution and nothing would be the same after that. Nevertheless, the Countess still portrays that sophisticated image of the Rococo, which is fashioned in the boudoir to show off in the living room. In the 18th century, the living room became the focal point of the home and an entire culture was developed around this room, from where illustration took off and the hostesses, a.k.a. “salonnières”, led the debates.

This century saw significant progress in the distribution of the home, with a clear differentiation between private spaces and social spaces, which is the origin of the current layout of the home. People no longer received visitors in the bedroom, and now the idea of privacy is conceptualised as the basis for this new layout. Small, cosy, private rooms were increasing in number, sometimes even divided into female and male rooms: the boudoir, the study, the literary room, the tea room… even the bathroom is segregated in some homes.

This work shows a soft cushion and a perfectly upholstered seat with soft lines, clues to what will become, along with privacy, another one of the century’s notions that will go on to play a fundamental role in the evolution of the home: the spirit of comfort. In spite of how it may appear, the less formal Versailles of Louis XIV actually contributed significantly to this quest for comfort, as demonstrated by the emergence of the armchair. However, comfort had its origins in the bourgeoisie, and it was the private hotels of the Parisian Marais that set the tone. Nevertheless, the prestige of the French court helped ensure that it was the French who paved the way and any trends that emerged, such as Rococo, radiated throughout Europe. Furniture catalogues emerged to help with this dissemination, although curiously the first such catalogue was attributed to a famous English cabinetmaker, Thomas Chippendale (The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director, 1754).

The quest for comfort forms the basis for modern ergonomics and furniture. In contrast to the rigidity that encouraged a formal posture, the seats curve and adapt to the body, and even to complex clothing such as that worn by the Countess. Upholsterers’ work is essential, as the padding and textured fabrics they use prevent the body from slipping. Their prominence also stems from the fact that they are true decorators who can change the appearance of an entire room with textiles alone. Curtains now emerge as a decorative element (the piece depicts one with a tassel that frames the Countess), while tapestries fade away in favour of panelling or wall coverings.

Cabinetmaking is also experiencing an unprecedented golden age, with cabinetmakers signing their furniture in the same way that artists sign their works: stamps became compulsory in France in 1751, as a guarantee of quality and recognition of value. Furniture has become highly sophisticated and, compared to its previous cumbersome and solemn nature, it is tending to become lighter and smaller (like the rooms themselves), which allows for mobility: occasional tables that can be brought out or put away as needed, which could be the case for the one depicted; or cabriolet armchairs with a curved back, which no longer rest against the wall and are easy to move. And, of course, different types of furniture start to pop up: dressers, desks, gaming tables and dressing tables, chiffonières, secretarydesks… People say that in Louis XV’s time there was a seat for every occasion, from cabriolet armchairs or Queen Anne chairs (with a flat back, against the walls of the room), to an endless number of types and postures when sitting: bergère chairs, sofas, love seats for two people, the chaise longue to stretch your legs, the voyeusechair to spectate at gaming tables, the chauffeuse fireside armchair...

Something in the work is already suggestive of the winds of change: although the chair has prominent sweeping lines and a scallop motif―a Rococo favourite―we can already spot a change of taste in the small table and the cup, marked by the discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum decades prior, and a renewed interest in antiquity.

Nicolaes Maes

The Naughty Drummer

Room 25

Nicolas Maes introduces his family in this work, at a critical moment for the little drummer boy, and includes himself, as can be seen in the reflection in the square mirror in the background.

The scene unfolds on the upper floor of the house, most likely narrow and deep and attached to other houses built vertically, given the scarce availability of urban land in 17th century Holland. The practical façades allow for large window openings like the one we see here, with the curtain completely drawn back to make the most of the light, clearly adapting to the environment. By that time, frames allowed windows to open inwards or outwards (casement windows) or vertically, like the sash windows in England. Window design was set to progress, and the size and number of windows was a sign of social distinction.

In this context, the differentiation between private spaces (binnenhuis) and spaces for public, social use (voorhuis) was already well established, and subdivision of the house by function began: living rooms, bedrooms, kitchen. The particular structure of Dutch society at the time, with the dominant bourgeoisie imposing its values and way of life, brought with it a new domestic culture that revolved around the private aspect of family life in the home. The home is, above all, the heart of family life. That a narrative like that of the naughty drummer is worthy of being the subject of a painting is quite expressive of this new concept of domesticity, the importance of which can be seen in the abundance of Dutch representations of family life and domestic interiors.

Life became more focused on privacy and home life, because there was a new, more defined sense of the family unit, in which women played a central role and childhood acquired a new prominence, as can be seen in this painting. In a predominantly urban environment, children spent more time at home because they were not sent out at a young age to work in the fields or as apprentices in workshops. More attention was paid to their education at school and at home, and people began to theorise about all of this. The greater presence of children strengthened emotional ties with them and, although in this scene we see the mother disciplining the child, there are countless images that portray tender interactions. In any case, the focus given to childhood in the nuclear family is evident, as can be seen by the cradle in the foreground, meticulously depicted by the artist, with a baby sleeping soundly (for the time being), swaddled to avoid the rigours of the Dutch, dank cold, which forced women to spend long hours sewing atop seats with platforms and leather backrests, another clear example of adaptation to the environment.

Lastly, note the use of wicker or rattan in the construction of the cradle and in basketry techniques, with ancestral roots in popular culture, applied to furniture. These techniques offer strong, lightweight (cradles were sometimes hung up to harness their swinging motion), affordable and highly comfortable solutions. They would enjoy something of a resurgence in the 19th century due to influence from the East and products arriving from the colonies.

Jan Jansz. van der Heyden

Corner of a Library

Room 25

This work by Van der Heyden depicts a library, a space for knowledge and enjoyment in secluded solitude, free from distractions, possibly of a private and, undoubtedly, secular nature. Perhaps the artist’s own library. We are no longer seeing a Renaissance studiolo or a cabinet of wonders, which had made the cabinet of curiosities an emblematic piece of furniture from the previous century. It is a library as we know it today, with a new design that demands a specific type of furniture: the bookshelf, attached to the wall, simple in shape and completely functional, with a drawn curtain that would protect the books from dust and light. The bookshelf was a departure from the medieval tradition of leaving books on tables and desks, a custom adopted in monasteries that continued well into the 15th century (as can be seen in the painting of Saint Matthew the Evangelist). Following the invention of the printing press, the ability to acquire a large number of volumes influenced this change.

The importance of cartographic and cosmographic elements (atlases, maps, terrestrial and celestial globes, the armillary sphere, etc.) is evident, conveying this desire to learn about all four corners of the world. The library is an ideal space for delving deeper into this knowledge and the Dutch were at the forefront of scientific development in this regard. The population’s fascination with maps, atlases and globes is demonstrated by the fact that they feature as decorative elements in the interiors of the period. They were not only regarded as scientific objects, but were appreciated for their beauty too, as can be seen by the care with which the artist has depicted all the elements of the piece, which even allows us to identify specific editions and models, equating artistic practice with the visual integrity of a cartographer’s work.

Knowledge of the world includes its exploration and conquest. The Dutch had the largest merchant fleet of the time, which was largely responsible for their enrichment. As an expression of this leadership in colonial trade, the painting shows oriental lances and a tablecloth, likely made from Chinese embroidered silk. Black lacquered walnut chairs, like the ones depicted here, became fashionable in the Dutch Golden Age, and their marquetry was also highly regarded. This moment marks the birth of an emerging global culture, not only through knowledge and cultural exchange, but also through trade. They manage to fit the whole world into one room, not just with globes and books, but also through products.

It is moving to think that the artist, proud to continue painting at such an old age (and only a year before he died), signed his name on an everyday object like the base of a candelabra with its nearly burned down candle, the symbolic value of which is not lost on us.

Gerard ter Borch

Portrait of a Man Reading a Document

Room 27

Despite the clear differentiation between public and private spaces already seen in Nicholas Maes’ work, bedrooms largely remain versatile spaces that offer a variety of uses. Some have fireplaces where people cook or tables where people eat or discuss matters related to public life, as could be happening in this painting by Ter Borch. Depicted in this space is a canopy bed and a figure sitting at a table, holding a piece of paper that seems to refer to his professional affairs or to his position in the public sphere, as also evidenced by the atlas open to a map of the Netherlands, elements that bring other dimensions into the privacy of the bedroom.

He is wearing lounge-wear, another way of differentiating between the public and private spheres, at a time when more efficient chimneys and windows provided better insulation from the cold and more comfortable attire could be worn inside. Iranian or Turkish rugs are not yet used for this purpose and play an eminently decorative role as coverings or are hung as objects of great value. Using them as floor coverings was a contribution from Georgian England, creating rooms that were not only warmer but also less noisy. The manner in which it is depicted here, the right way up and folded back, allows us to appreciate its quality and is characteristic of an empiricist culture supported by the visual exploration of the world.

The bed, with its four-poster structure, the rug, a painting and a moulding above the door constitute the room’s entire decor, in a typically Dutch sobriety fitting of its bourgeois pragmatism and the search for solutions in the distribution of the home. But in contexts where there has not been as much progress as here in the differentiation of spaces, the bedroom remains the centre of the house and is the space in which people spend the most time. Let’s not forget that the bed was still the most comfortable piece of furniture, and it was not frowned upon to receive guests from the comfort of one’s bed or even sit on someone else’s bed. From the 16th century, the use of “day beds”, as distinct from night beds, was considered normal and was inspired by the klinai used in Greco-Latin triclinia. These day beds reached peak popularity in Rococo France in the form of a chaise-longue.

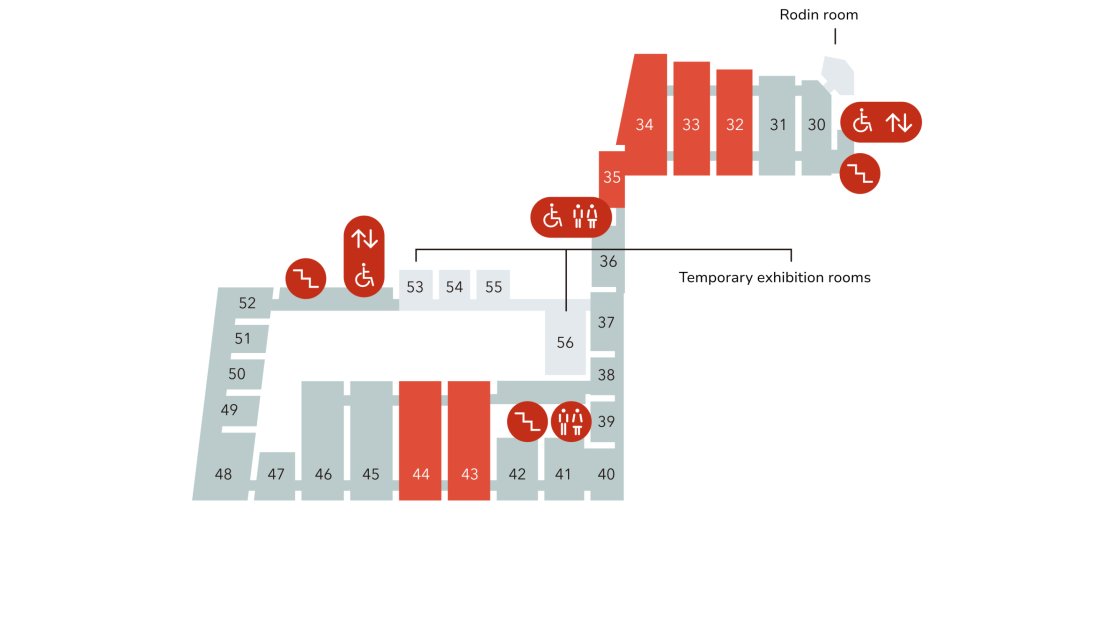

Artworks on the first floor

And it moves forward in time to the 20th century

John Frederick Peto

Books, Mug, Pipe and Violin

Room 32

If Memling’s jug encapsulated the symbolic and decorative value of objects in defining the home, this still life by Peto depicts a more personal symbolism, with objects that seem linked to a specific identity. These are everyday objects and, in some cases, their functional meaning is obvious, but one of the most evocative aspects is the depiction of worn surfaces, those signs of use left behind by a particular person, as well as the passage of time. They are the “signs of life” that the artist is purposefully depicting through the textures and materiality of the painting itself, in a work that is symbolic of him, compared to that of other, more famous still life painters, such as Harnett, who depict objects with a less worn, but also less unique, appearance.

Through the deterioration of these objects, Peto depicts the special attachment that someone must have to them, which makes them a kind of portrait and embodies the narrative power of the objects. What are they telling us? Is this an unmistakably masculine still life, with forms of leisure that were seen to be masculine at the time? In any case, it is a subjective view conveying tastes and preferences: music, reading, tobacco... Could it be a self-portrait? Peto is known to have played the violin since childhood, and he was passionate about books. Be that as it may, this artist does usually include elements that are part of his private life in his paintings (although this does not seem to have been the case with the pipe).

Aside from their appearance, Peto has not chosen objects of special material value; he wants to express something different: the emotional value that owners place on certain items. Some possessions are cherished for a lifetime; they are repositories of memories and experiences, of identity, things perhaps received from a loved one and that conjure up memories of them when they are no longer there, comforting objects from childhood...

A piece like this shows that there can be a strong emotional component in our relationships with objects, that a bond can be established that transcends the merely practical, the aesthetic and the material. Something that the designer must have taken into account when practising his profession and that Donald A. Norman addressed in his now classic book “Emotional Design: Why We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things” (2003).

Berthe Morisot

The Psyche Mirror

Room 33

Times were changing when Berthe Morisot painted this work. Following the French Revolution, stamps were no longer mandatory and by the mid-19th century, a mechanised furniture industry had already established itself, bringing with it all the effects of cheaper production and easier access to products. The iconic Thonet chair number 14 is symbolic of this change, the epitome of productive efficiency paving the way to democratising design: with just 6 pieces of wood, 10 screws and 2 nuts, using the innovative bentwood technique introduced by Thonet in 1830 and designed for mass production, it was one of the first examples of flat-pack furniture design that was easily transported to and assembled at its final destination, which explains its worldwide impact. Simple, functional and economical and still in use today, it had all the components that would go on to characterise the modern furniture and design industry.

Although Thonet chairs may have succeeded in cafés, the taste that manifests itself in bourgeois interiors like the one depicted is remarkably conservative. Hygienist trends, somewhere between scientific basis and fashion, dictate that light and ventilation are essential for creating a healthy atmosphere in the home, something that can be seen in the noble floors of the houses renovated by Baron Haussmann and in this painting through the depiction of large windows.

Solutions for comfort continue to be explored, such as the steel spring armchair that Morisot painted here, one of the pieces of the time, as well as the quilting that accentuates its soft appearance. Perfectly co-ordinated upholstery and curtains tie the scene together and create the feeling of well-being and privacy in a room that is now strictly private, that the subject of the painting somehow seems to blend into. She prepares for that perfectly staged setting that the bourgeois class demands, whether it be visits, dinners, dances, concerts... always accompanied by others. Displaced from the public sphere and elevated to the status of “angel in the house”, the woman nevertheless lacks “a room of her own” in which to self-actualise, beyond the dressing table and the private ritual of dressing and grooming. She is, however, conquering certain areas of public space through her urban incursion into the new temples of consumerism: department stores. A novel sales concept that emerges in this sphere to provide an outlet for booming production and, as a result of its development, the dissemination of illustrated product catalogues, the first interior design magazines and catalogue sales.

She looks at herself in a dressing mirror or psyche mirror, larger than those previously seen on this journey. The French had been dominating mirror production since the 18th century, after establishing their own industry in response to growing demand from Versailles, which would end up replacing the traditional Venetian blowing method with a pouring method that allowed much larger sheets to be manufactured. The mirror in question is known to have belonged to Berthe Morisot. Could that be her gazing into it? An encounter between a woman and herself, painted by an artist, in a gesture telling of appreciation and self-affirmation, as well as of that growing need to find one’s own space, both in and outside the home.

Pierre Bonnard

Misia Godebska

Room 33

The woman portrayed here is Misia Godebska, an iconic hostess in Paris at the time, and friend to the most prominent artists and writers. Picasso, Cocteau and Chanel were among her companions and she made sure to introduce them to each other at the intellectual hub that her house became. Bonnard depicts the living room of her luxurious home on the Quai Voltaire in Paris.

Misia had commissioned the artist to paint the decorative panels seen in the background. When seen together with the eighteenth-century sofa, the cushions, the rug and even the subject's attire, the viewer is immersed in an atmosphere of historicist luxury, which may seem surprising given the apparent contrast with the spirit of the avant-garde artists who frequented her house and even with the modernity that she herself could embody.

It is a period for 19th century Gothic and Baroque revival, any furniture named after the last Louis' of France... sometimes mixed in a motley eclecticism. The wealthy haute bourgeoisie revived styles and collected antiques as a way of strengthening its prestige and legitimising its social relevance through the past, in clear contrast with the thriving modernity of an industrialism that it itself promoted and that now provided other solutions: in contrast to the exclusivity of unique panels painted by an artist, as seen in the background, the city abounded with wallpaper. This wallpaper could be found in a wide range of different qualities, from very expensive, hand-painted wallpapers from China, difficult to distinguish from a fresco, to those mass-produced by industry, which were much cheaper. A growing sector of the population was seeking greater accessibility to products in line with the egalitarian society it wants to promote, while the bourgeois set offers a historicist refuge from the currents of change.

In the midst of the cultural and stylistic crisis unleashed by expanding industrialisation, Art Nouveau emerges in response with a promise of newness (Nouveau), modernity (Modernismo), youth (Judgenstil), rupture (Sezession) and freedom (Liberty) aiming to be the face of the new era. Sensual, organic and highly decorative, it is not depicted in this work, but it is in tune with the resistances indicated earlier. If the age of technical reproducibility saw a constant search for distinction through manual and artistic production, Art Nouveau, with its organic, sinuous and curvilinear appearance, evokes the refinement of the handmade.

However, there is also a democratising aspect to Art Nouveau: one of its pioneering and flagship manifestations was Victor Horta’s town house, and its most eloquent expression can perhaps be found in Guimard’s Paris metro sign. It also achieved widespread dissemination through the graphic arts and the growing mass media. Although, by the time this painting was created, there were those who were already denouncing ornament as a crime. Industrial production and modernity increasingly demanded another kind of visual and formal culture.

Oskar Kokoschka

Portrait of Max Schmidt

Room 34

There is nothing obvious in this work that embodies the evolution of domestic design, but the figure portrayed helps us to put a face to the contributions that came from Vienna at the turn of the century, as well as to the contradictions present in the imperial, aristocratic capital par excellence yet also the epicentre of cultural modernity.

This is Max Schmidt, a businessman, patron and collector, who kept the triple portrait of the Schmidt Brothers (to which this fragment belongs) until his death. The brothers owned an exclusive interior decoration firm founded in Vienna in 1854, which handcrafted furniture for the Viennese imperial court and haute bourgeoisie. Max Schmidt himself occasionally worked as a designer and was part of the team behind the famous elephant trunk table, along with W. Berka and Adolf Loos, the latter a co-worker at the firm and mentor to Kokoschka at the start of his career.

It was Loos who in 1908 published “Ornament and Crime”, a manifesto of his thoughts on aesthetics, where the search for a radical truth is translated into the defence of structural forms and the condemnation of ornament as falsehood. That is why he very much liked the crudeness with which Kokoschka expressed himself in his “black portraits”, many of whose commissions Loos encouraged, as is the case with this work.

Although not as radical as Loos’ ideas, it is nevertheless possible to identify a trend towards aesthetic purification that will start to shape the evolution of modern design. The Vienna Secession in Austria had already assumed a flatter and more geometric style compared to the organic and sinuous styles of Art Nouveau. Something similar was happening elsewhere, such as in the Anglo-Saxon world.

Two members of the Vienna Secession, J. Hoffmann and K. Moser, founded the Viennese Workshops (Wiener Werkstätte) in 1903, a co-operative for promoting modern decorative arts with which Kokoschka, as well as Klimt and Schiele, collaborated. Its integrationist approach to design is based on the craftsmanship and artistic quality of products, as demonstrated in one of its flagship projects: the Stoclet Palace in Brussels (1905-1911). A “total work of art” that would be Loos’ worst nightmare, as he described in “Poor Little Rich Man”, where everything relates to a scheme and even the subject’s slippers have to match the rest of the decor. But here, too, a deviation from ornament had begun. It can be seen in the façade of the Palace or in the furniture designed by Hoffmann, with its rotund lines resembling architectural plinths.

Although the Stoclet Palace and most of the objects made by the Viennese Workshops exude exclusivity, demonstrating in passing that the geometric trend was not at odds with luxury and sophistication, a new sense of form is emerging that is already paving the way for mechanistic aesthetics, which in its simplified lines, free from superfluous elements, finds the most easily standardisable form, capable of being produced on a large scale. An aesthetic formed in the wake of modern design, also understood in its drive for democracy.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Fränzi in front of a Carved Chair

Room 35

A girl with a green face is a true aesthetic manifesto for the liberation of colour. Without its representative function, colour is regarded as a vehicle for emotional expression and modernity, in a work that introduces the viewer to a new experience of colour in contemporary visual culture. Its execution, with its thick contours and deliberately rough brushstrokes, also depicts an emotion that Kirchner and the expressionists connect with in the artistic manifestations of non-European cultures, nods to which can be seen in the girl’s mask-like face and her necklace. It was not just a formal repertoire from which to draw inspiration, but a real life reference that they tried to put into practice during their stays on the lakes of Moritzburg, the North Sea or the Baltic: living in a wooden cabin in nature, in a creative community, producing your own furniture and going naked, playing boomerang...

The group’s scepticism (if not outright rejection) of industrial progress and the acceleration of modern life advocates a return to nature and an appreciation of the simpler ways of life. Kirchner would end up living in the Swiss mountains after the First World War, the first mechanised war.

This attitude was nothing new. Since the last decades of the previous century, the Arts & Crafts movement had witnessed the ravages of industrialisation in its birthplace: terrible working conditions, division of labour and dehumanisation, mass production and poor-quality products, ugliness... William Morris, the charismatic and multifaceted soul of the project (architect, designer, craftsman, writer, poet, activist) defends the return to crafts as a way to alleviate these evils and lay the foundations for a fairer society, inspired by an idealised Middle Ages and nature. A view on craftsmanship that differs greatly to that seen thus far on this journey (associated with exclusivity), making Morris a pioneer in lending an ethical aspect to design.

In their return to a simpler way of life and testament to their admiration for other cultures, Kirchner and other members of the Die Brücke collective produced their furniture, such as the carved chair on which Fränzi is sitting, by hand. Furthermore, the very execution of this painting, like so many others by the artist, is reminiscent of wood carving and magnifies its materiality.

Morris’ criticism of the harmful impact of industrialisation was accurate, but mass production was not all bad: as production increased, prices became cheaper and products became more affordable. Craftsmanship, however, has its limitations and cannot meet the needs of a growing population. Morris had wanted to bring beauty and well-being into the everyday lives of everyone (“I do not want art for a few, any more than education for a few, or freedom for a few”) but he often, frustratingly, found himself producing objects for the elite. Perhaps a certain escapist attitude, like that of the members of the Die Brücke collective, prevented him from seeing the benefits of industrialisation, which could be used to realise his democratising dream, but which were impossible to resolve under the artisanal terms he had proposed. A utopia then remains pending, which the Bauhaus would pick up where Arts & Crafts left off.

Piet Mondrian

Composition in Colours / Composition No. I with Red and Blue

Room 43

For many people, the profound formal experimentation in Cubism in the years leading up to the Great War represented a point of arrival through which to chart their own paths. Such is the case of Mondrian and his neo-plasticism. It is amazing to think that almost a hundred years have passed since a work like this, and even more so for other similar works. The artist achieves a kind of everlasting modernity in these works, even though it may seem contradictory, which makes them appear radical in their minimalistic expression to this day. Precisely for that reason, for having distilled a language to its purest essence, one could say that they are timeless and, in some way, absolute, universal. For Mondrian, geometric abstraction acquires these meanings, which concern the spirit and an objective and immutable order.

But the geometric reduction of form, in the context of an industrialised society, also concerns substance. Cubism had opened the doors to a new visual culture that would soon go beyond painting and be applied to the world of everyday things. Geometric shapes are versatile, interchangeable and can be applied to architecture, furniture design, fashion and graphic arts. They are also the best shapes for mass production.

Founded in 1917, the De Stijl journal brought together like-minded artists and architects, including Mondrian, who from the beginning sought to integrate the arts through what Van Doesburg called a “new aesthetic consciousness” in the first issue of the publication. One could argue that De Stijl was one of the first to consider abstraction in terms of design and architecture.

The chair by Gerrit Rietveld, also associated with De Stijl, is often seen as a manifestation of this integrationist approach. Looking at it feels like seeing the sketches of a Mondrian painting cut out and assembled to create an everyday object. Rietveld is also behind what can be considered De Stijl’s architectural manifesto, the Schröder house (1924), which he built in collaboration with Truus Schröder-Schräde herself, future owner of the house in which Rietveld would end up living. Neither of them had any architectural experience at the time, so they felt free to make the house exactly as they wanted. The bedrooms were located on the first floor, and their flexible layout, based on sliding walls, was a milestone, as the space could be adapted to different needs. For Truss, these were determined by the relationship with her three children, according to a non-conventional parenting model that inspired the search for absolutely novel solutions in the home, recognising the importance of children in its layout.

After the social failure of the Great War, a material and spiritual reconstruction of the world was necessary through radically new forms and solutions, in a renewed proposal to unite art and life, which is what projects such as De Stijl, and also the Bauhaus, brought with them.

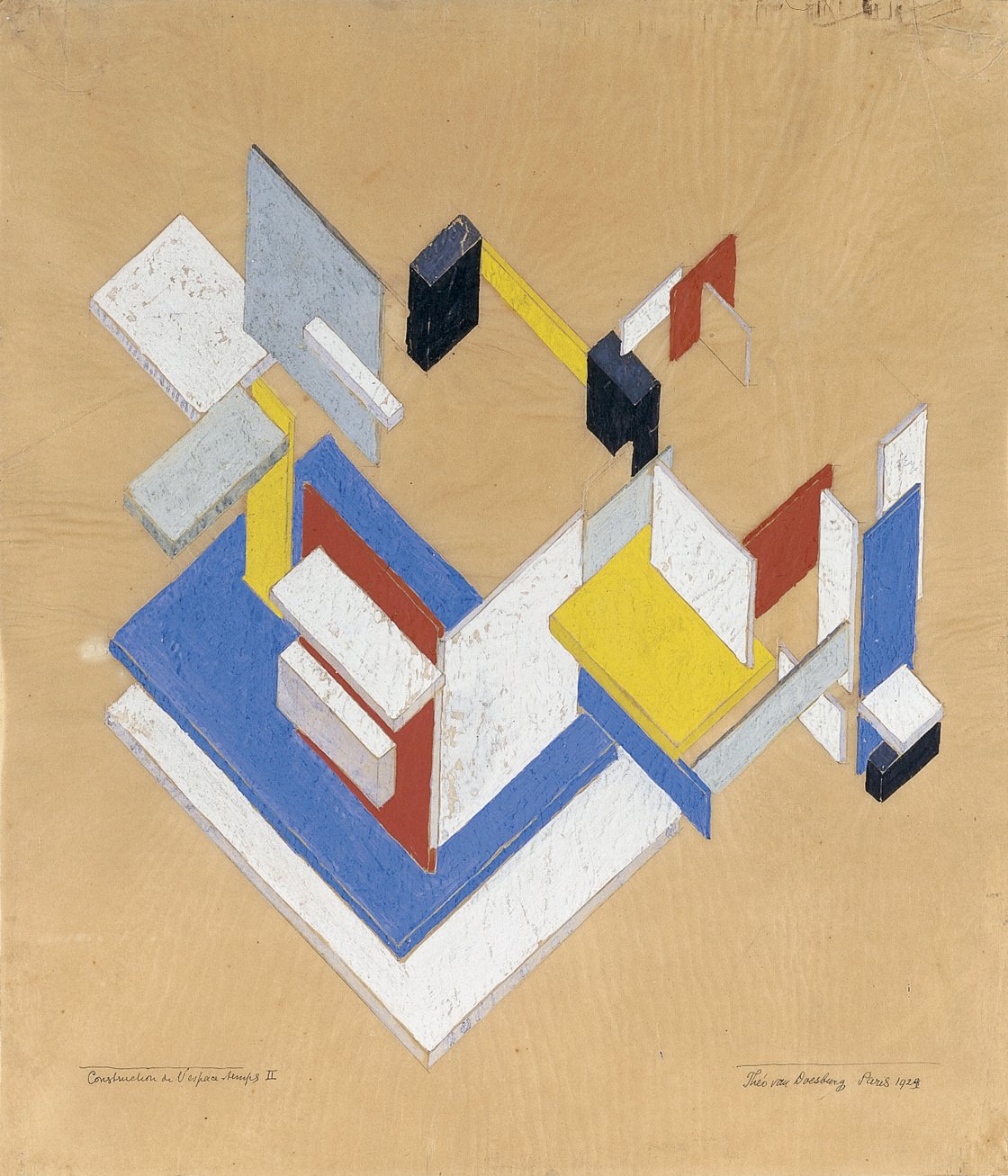

Theo van Doesburg

Construction in Space-Time II

Room 43

Perhaps two souls co-existed in De Stijl as they would later do in the Bauhaus. If Mondrian represents its most spiritual side, Van Doesburg would represent its applied vision, in tune with the constructivist spirit. We ought not fall into such strict dichotomies though, because Van Doesburg had also dabbled in theosophy and therein lies the undoubted influence of Mondrian in the world of material forms.

Van Doesburg developed a greater interest in architecture, which even led him to abandon painting for a time in order to devote himself to his architectural projects and redefine the principles of De Stijl. For him, geometric abstraction meant achieving an exact language, devoid of particularities, that allowed different disciplines to work in collaboration.

In this work, the planes are raised and introduce space, as in an axonometric projection. In fact, this work is part of the preparatory drawings for the design of the house-cum-studio that Van Doesburg and his wife planned to share with Hans Arp and Sophie Taeuber, which was never finished. It is a somewhat abstract architectural representation, with no windows or other functional allusions, but which inevitably adopts the diagonal to suggest the third dimension. When Van Doesburg started to use diagonals not only in compositions like this one, but in more fully illustrated ones, Mondrian definitively separated himself from De Stijl.

The diagonal, which beyond spatiality provides dynamism, was more connected with the visual experiences coming from Russia than with neo-plasticism’s static plot of horizontals and verticals. Van Doesburg had met El Lissitzky a short time before, in Weimar, where he made contact with other constructivists and with a school that had recently opened its doors: the Bauhaus. These were key years for the evolution of our artist. Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, had been impressed by a lecture given by Van Doesburg and invited him to the school in 1921. Van Doesburg went a step further and settled there, likely thinking he would be hired as a teacher at the school, although his highly critical nature made this very difficult. “You are all romantics”, he told them, fully imbued with the spirit of constructivism, attacking the expressionist character of the school from the pages of De Stijl. Nevertheless, he stayed in Weimar, teaching courses at his home (attended by many students and teachers from the school) and organising constructivist projects there and later in Berlin.

Perhaps Van Doesburg’s criticisms were somewhat true because it wouldn’t be long before there was a turning point at the Bauhaus, with the simultaneous influence of Russian trends brought by El Lissitzky, of the constructivism of Moholy-Nagy and of Van Doesburg himself as a catalyst. The school reconsidered its objectives and procedures to establish an approach that was more mechanistic than subjective and artisanal, more in line with industry, to which the reductionist aesthetics of neo-plasticism (filtered through Van Doesburg) would have much to contribute.

Paul Klee

Revolving House

Room 44

Klee had been a teacher at the Bauhaus for a few months when he painted his Revolving House and in it, he seems to echo some of the trends that ran through the school, from a playful and humorous perspective. We can see that the geometric reduction of form, which is so important to mechanistic aesthetics, takes on an almost childlike appearance, like someone playing at painting a house as a child would. For its part, the applied vision and architectural sense of constructivism, which were already having an impact in the Bauhaus, are translated into a display that opens up the house, deconstructs it and transforms it into something dynamic, revolving, through a centrifugal force.

Klee had just started at what is considered a pioneering school of modern design and would become a long-term teacher there, witnessing the numerous changes it would undergo throughout its short-lived existence (1919-1933). Founded in post-war Germany, the Bauhaus, “building house”, set out to achieve what was still a utopia: quality design accessible to all in order to build a better society. Its evolution was shaped by the search for the best means to achieve this objective.

In a way, it picks up where Arts & Crafts left off, trying to adapt its ideal of artisanal production to the new times, so the school is initially organised as a workshop that even reproduces the guild division into masters, journeymen and apprentices. The spirit of the early days is largely attributable to the importance of expressionism in Germany. Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, had belonged to a group of architects who studied the Gothic style of modern architecture in iron and glass and the natural style of geometry, such as that of glass. Klee also promoted the geometry of nature. This crystalline utopia is portrayed in the image of the “cathedral of the future”, which is the image Feininger chose to illustrate the inaugural manifesto of the Bauhaus, and even Mies van der Rohe, the standard-bearer of modern rationalism and the school’s last director, is indebted to this style.

But since the Bauhaus was all about “learning by doing”, they created prototypes for industry and began to realise the difficulty of achieving their democratising objectives in artisanal terms: it was difficult to produce such objects economically and adapt their forms to industrial production. In contrast to the visionary and spiritual character, a constructivist soul was gradually imposed given the need to change focus and, in 1923, the school was opened up to the public through an exhibition with the slogan, “Art and technology: a new unity”. Two years later, the new headquarters in Dessau fully embodied this change. The iconic image of this new rationalist Bauhaus is also found in Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture: an innovative material, adapted to industrial requirements and the standardisation of shape for mass production, with a refined and mechanistic aesthetic in which “form follows function”.

The Nazis’ rise to power in Germany brought the school programme to an abrupt halt and once again postponed the democratising utopia. After the war, however, Bauhaus edges were perceived as too harsh and its mechanistic aesthetic and steel were considered cold. Humanised versions of modern design were finding their place, incorporating the organic softness of curves and the traditional warmth of wood. An approach that Klee seems to glimpse in a work like this, whose notable materiality of earthy colours on fabric glued to paper conveys the closeness of the materials whose qualities he tries to replicate, brick and cement, which human beings have traditionally used in the configuration of the home. They are also materials that come together in the modern-day house and in the one painted by Klee, constantly transforming, with a multitude of angles and possibilities. This house may symbolise the utopias yet to be realised in living spaces.