Fashion

María Corral Aznar

"Know first who you are, then adorn yourself accordingly."

Epícleto (1st century AD)

Fashion is a way of differentiating ourselves. It allows us to exhibitour different attitudes to life; it can show off or hide our bodies; it can challenge or innovate; it can be modern or traditional. Fashion reflects the evolution of society over time. It is an integral part of our culture and therefore has a place in our museums.

The Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum invites you on a journey through the world of fashion. Through the paintings in the collection we can see the continual change in the language of fashion and its styles. As we walk through the rooms, we will discover the evolution of clothing: the fabrics, the textures, the colours, the shapes and the attitudes towards the art of dressing.

Starts on the second floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

The Nativity

This painting by Jacques Daret, a contemporary of Roger van der Weyden, was created when the Duke of Burgundy was at the height of his power. It was a time when the artist was a favourite at the Burgundian court. The work depicts the story when Joseph went to look for two midwifes to help the Virgin give birth. When they all arrived back at the stable Mary’s son had already been born. As the two women entered, the first immediately recognised the purity and virginity of Mary. However, the second midwife was less trusting and wanted to see proof of the miracle. She was punished with paralysis in her hands. The painting shows the moment in which the second woman is about to touch the Baby Jesus so that he can heal her.

In the 15th century a more resplendent period began, which gathered momentum when the first modern nations were formed. The agricultural revolution gave way to the generation of great extravagance and the emergence of guilds. Trade became more efficient, and with it grew the exchange of fabrics and adornments, which fired the inspiration of the tailors.

At this time the fashions become more sophisticated and exaggerated; clothes had pointed edges with an ornate, floral Gothic air. The thickness of fabrics in Flanders lent clothes a sombre and extravagant touch. Dresses followed the form of the body, outlining its shape. The waist was highlighted directly under the bust and a wide belt was worn to create vertical pleats on the skirt below. Skirts fell right to the ground, and the trains at the back of the dresses were of varying lengths depending on the wearer’s social class (the longer the train, the more socially elevated the lady).

Previously it had been considered immoral to uncover one’s head and show hair, but in the 15th century complex and imaginative headdresses began to be worn, more and more so as the century progressed. There were a number of different types of headdresses that had become fashionable: the crespine, which had a hairnet that allowed the hair to be plaited and twisted in two buns over the ears; à corné (with horns), padded rolls, turbans, and the hennin, a cone-like headpiece that had a veil sewn on to the upper part. The conical hennin was particular popular in France, whilst the steeple hennin was very fashionable in England. The most eyecatching of all designs was the butterfly headdress, which was made up of a wire frame attached to a small cap to collect all the hair. The frame held a transparent veil that looked like butterfly wings.

In this same room you will find the painting Pieta Triptych by the Master of the Saint Lucy Legend. The figure to the left is wearing a cotehardie, a dress with a v-shaped décolleté trimmed with fur. Her sleeves are narrow and tight which was particularly fashionable at the time.

In Clothing the Naked by the Master of the View of Saint Gudula we see the different types of headwear that men wore during this period. The most common was the turban, which initially had been a long cone on which you could drape fabric in all sorts of different ways. Men of all social classes wore it throughout the century. The chaperone came later. This headdress simply could be worn and did not have to be specially arranged. As time went on, the chaperone became smaller in size until men who belonged to guilds only wore it. In the 19th century coachmen wore this type of headdress.

During this period men’s shoes had elongated toes, which were sometimes exaggerated. However, the civil and ecclesiastical authorities strongly disapproved of this fashion. Edward III of England even introduced a sumptuary law specifically stating that «No gentleman may wear shoes with a toe longer than two inches without incurring a fine». However, this measure was ineffective and in his successor’s reign the toes of men’s shoes reached eighteen inches or more in length. They were called crackowes. Apparently, the name came from the time when Richard II married Anne of Bohemia (1382), and the Knights of the entourage arrived at the English court with exaggeratedly long pointed shoes. This style of shoe was fashionable for a long time, and to counter the instability that such footwear produced, their soles were made of wood.

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni

The new artistic style of the renaissance came about largely due to the increased commercial prosperity in Italy. The new lines in painting were horizontal ones; shoes, necklines, and shapes in general, echoing the new style of architecture. Italian fashion quickly spread to the rest of Europe.

Renaissance painters looked to classical antiquity. The human figures were of ideal proportions, just like the one in this exceptional painting that is a splendid example of the 15th century portrait. The woman in the painting is Giovanna degli Albizzi who was married to Lorenzo Tornabuoni. She died two years later carrying her second child.

Her dress shows her elevated social station and the prevailing taste for sumptuous fabrics. In this case her dress is made of magnificent silk embroidered with intricate patterns. This type of fabric is called brocade and was made by weaving motifs with gold and silver threads.

The silk sleeves are slashed, according to the 15th century Italian fashion, with several openings that show the folds of her white shirt neatly tied under her dress. The neckline is square and the bust is corseted. At this time women began to wear corsets, a step that would change the aesthetic ideal of the female figure for the following four centuries. The corset was a whalebone structure that would squeeze a woman’s waist like a funnel to enhance her cleavage. From then on the fashion for women was very constrictive, forcing women to stay very straight pushing their shoulders back. Headdresses disappeared at around this time and hairstyles became more natural by reducing the volume and wearing ringlets to frame the face.

Other paintings in the same room allow us to assess the differences in European fashion. The figure in Portrait of an Infanta by Juan de Flandes, wears a Castilian costume typical of the period, independent of foreign influences. The most important Spanish contributions to fashion were the use of linen shirts, the farthingale (a hooped skirt), and chopines, women’s platform shoes that were originally worn my Muslims. The manner in which the Spanish ladies plaited their hair, by intertwining their hair with ribbon to form one plait, was also unique to Spain.

The austerity of the Spanish court is clear from the sumptuary laws introduced by the Catholic Kings to curb spending on luxuries and to maintain social order: «Those who are not aristocratic may not wear silks, furs or dresses reserved for the social elite».

There is a dominance of the colour black, which was a sign of dignity, sobriety and authority of the person who wore it, as seen in the works of Antonello da Messina, Andrea Solario and Joos van Cleve. The black dye was produced by mixing tree gall and green vitriol, and as a result obtained a deep black hue. However it faded over time and damaged the fabrics. Superior methods of dyeing black fabric reached Europe via the Spanish conquests of the New World and were distributed to the rest of Europe. For example, logwood was adopted by the Austrians and called the «Spanish dress» colour, as was cochineal; the dye that created the bright red colour that cardinals wore.

The wide variety of male portraits we have looked at also show the evolution of men’s hairstyles. At the beginning of the 15th century men would wore their hair long and loose with a fringe. However, by the middle of the century they wore more hats of various shapes: mortarboards with jewels and feathers, bonnets and chaplets.

Portrait of Henry VIII of England

This portrait of the famous english monarch is an excellent example of Holbein’s talent and style, which is characterised by the scale and the psychological depth of his subject. The painter has managed to portray the personality of Henry VIII through his stance and the position of his hands depicted frontally.

In this portrait the king’s bodice takes centre stage because it was the most important part of a man’s outfit as it represented his masculinity. The shoulder pads add to this by making the thorax look even larger.

The style of the sleeves widened as the century progressed; they were detachable and were often slashed. Some men also wore two-coloured sleeves. In the early 16th century it became common practice to pull out the lining through the rips in the sleeves.

Thanks to Henry VIII’s wardrobe inventory we know that this monarch owned a number of bodices of different fabrics, sobrimost of which were made of velvet with gold lining. The most spectacular was a purple satin bodice with gold and silver thread detailing and pearl trimmings. Some of his bodices were entirely encrusted with diamonds, rubies and pearls giving extra support to the fabric.

Over the bodice, men would wear a jacket or jerkin (a 16th century tunic in Spain). This garment was made of doublelayered fabric that at times could be closed with ties or buttons at the front. On top of this men would wear a tunic over the shoulders trimmed with fur.

Furs were often used for both men’s and women’s clothing; the most popular were lynx, wolf and marten fur, which was used exclusively by the aristocracy. Breeches and tights were sewn together and covered the led. The breeches were attached to the jacket by straps; i.e. cord was passed through small holes and tied to attach the two garments.

Portrait of a Lady

The reformation in the 16th century spread across Europe, especially throughout Germany, and brought about a more sober style of dressing.

Hans Baldung Grien was the most gifted disciple of Dürer. This is the only female portrait painted by Grien that has survived. The identity of the sitter is entirely unknown. Most probably it is an abstract representation, an ideal image of a lady, rather than a portrait of somebody in particular.

The woman wears a dark green velvet dress with a belt around the waist and very wide sleeves with folds of fabric that fall to the floor (train). Velvet, silks and brocades all adorn her figure. A gold chain and a pearl chocker decorate her square neckline. She wears a hat with feathers and a string pearl headdress that gathers her hair in a hairnet.

In the Portrait of Anne of Hungary and Bohemia by Hans Maler we see a similar style of headdress: a hairnet holding the hair in place under a hat decorated with pearls.

In paintings such as The Court Jester known as «Knight Christoph» by Hans Wertinger, the Portrait of Ruprecht Stüpf and the Portrait of Ursula Rudolph by Barthel Beham and the Portrait of a Woman by Lucas Cranach we can see how men were beginning to wear a wider variety of clothes. The jerkin was still the most important piece in a man’s wardrobe, however on top of this he would wear a kind of overcoat called a schaube, which would usually not have sleeves and would be trimmed with fur. The schaube became the typical piece of clothing that the Humanists wore. Luther wore one and defined what the Lutheran clergy still wear today. The dress of a mayor was similar to the clothing worn by academics, but included a golden chain to be worn around the neck. This cape soon became an indispensable item of clothing. Initially it was mainly used for riding and outdoor activities, but during the second half of the 16th century it was used both outside and inside.

In Germany the colour red was used a great deal. In almost all of the portraits by Cranach of German princes, the sitters are wearing at least one item of red. During this period the lower classes were forbidden to wear this colour red and therefore it was often included in portraits to emphasise the nobility of the sitter, for example in the Portrait of a Woman aged Twenty-Six by an anonymous German Artist of the School of Lucas Cranach, the Elder. During the Peasants’ Revolt of 1524 in Germany one of the demands made by the rebels was to be allowed to wear red clothes like the aristocracy.

Fashions changed a great deal in the middle of the 16th century due to the personal tastes of Charles V, who was well-known for his sobriety. This is reflected in the Portrait of the Emperor Charles V by Lucas Cranach displayed in this room. The growing power of the Spanish monarchy influenced tastes in fashion in other courts. When Philip II came to power, the fashions of the Spanish court were admired throughout Europe.

Saint Casilda

His father’s work in the textile industry, the significant changes in the fashion industry during the 17th century, the theatre and Francisco de Zurbaran’s enormous creative talent were reasons why Zuberan’s series of holy martyrs became an artistic and commercial success on an international level. One needs only to look at the fact that works of this kind were exported as far as to the New World.

The artist’s perception of Santa Casilda is modern, even though the protagonist is the daughter of an 11th century Arabian King who converted to Christianity and was martyred for her faith. Zurbaran does not wish to reflect the pain of her martyrdom; on the contrary, here he emphasizes the femininity of the 17th century woman, portraying her at the peak of her virginity, with majestic clothes of rich, flowing and colourful fabric, adorned with precious jewellery. She bears her martyrdom with holiness.

Zurbaran habitually attended the religious plays that were performed in Seville in order to gain inspiration for the outfits of his maiden saints. It was there that the artist developed his particular stereotype of the female image, one that formed part of the baroque ideal and that centred on the patron’s aesthetic enjoyment of the holy image.

«No, these are not frivolous fashions. When I paint these holy women dressed like this, I do so in order to impart greater realism to the image. I only have one mission: to move closer to God. This is no mere personal whim of mine, nor of my clients. It is authentic religious painting which moves anyone who sees it.» ” (Francisco de Zurbaran)

The artist was inspired by the fabrics that he had brought from Venice to design these outfits. In 17th century Spain such magnificent silks were not yet being produced. He chose the colours, combined the prints and treated the fabrics himself. The saintly woman is wearing an orange toe guard, over which the velvet brocade dress is draped. The bottom border is embroidered with gold, pearls, emeralds, rubies, and garnet; the sleeve of the dress is finished with studs, a theatrical decorative element popular amongst painters. At the back, a voluminous silver silk taffeta cape finished with gold thread bobbin lacework falls to the floor.

Zurbaran’s dresses have been an important benchmark and reference point for designers. In 1961 Balenciaga designed an evening gown inspired by Santa Casilda, and even Coco Chanel cited Zurbaran as one of the first fashion designers.

Portrait of a Young Woman with a Rosary

Rubens painted this portrait of an unidentified lady upon his return from Italy. He had married and had been named the official painter of the Arch Dukes of Burgundy. He upheld his political commitments in the Netherlands through the fulfilment of many diverse assignments. As his fame increased, he set up a large and efficient workshop in order to respond to growing demand. With this painting he broke into a broader market in which portraits became evermore important.

This picture highlights the masterful lace work of the neck ruff, cuffs and headdress. It seems that it was in Italy that the idea first arose to pull apart the thread of the white fabric used in handkerchiefs and undershirts, and then knit it to create transparent motifs and geometric shapes.

This technique is called lace. Silk or linen thread are the best fabrics for making lace because of their delicacy and strength. Italian lace makers used needles whilst those in Flanders used spindles. High quality lace was always an expensive item as it was handmade by specialists and involved a very time consuming process.

Other paintings in the room showing fine lacework include the Portrait of Jacques Le Roy by Van Dyck and the Portrait of Antonia Canis by Cornelis de Vos. The lace neck ruff first appeared in 1570 and marks a great milestone, especially in the Netherlands. It served to keep the head upright and was a sign of aristocratic privilege. Over the course of the century ruffs would increase in size eventually becoming so large that it is hard to imagine how those who wore them were able to eat.

Later the neck ruff evolved into new variations such as the cartwheel neck ruff, which was made up of numerous starched tubular pleats. This was achieved by using a stick-work frame upon which the starched cloth would dry and acquire its consistent pattern. Once dry, the sticks were removed. The invention of this starch-based method, denounced by puritan moralists as a sign of vanity, did away with the wire frame as well as the support that had previously been necessary to make them.

A defining feature of women’s clothing in Rubens’ portraits at this time was his silver coloured and gold trimmed stomach pieces. This garment constituted the front half of a dress. It was hardened by cardboard and kept in place by rigid frames that were often made of wood. The skirts would protrude outwards with the support of a farthingale, an underskirt consisting of wire, wooden or whalebone rings which ran round the inner edge of the skirt. This was originally a Spanish invention, and in fact Spain would set the trends in fashion during the following century as well.

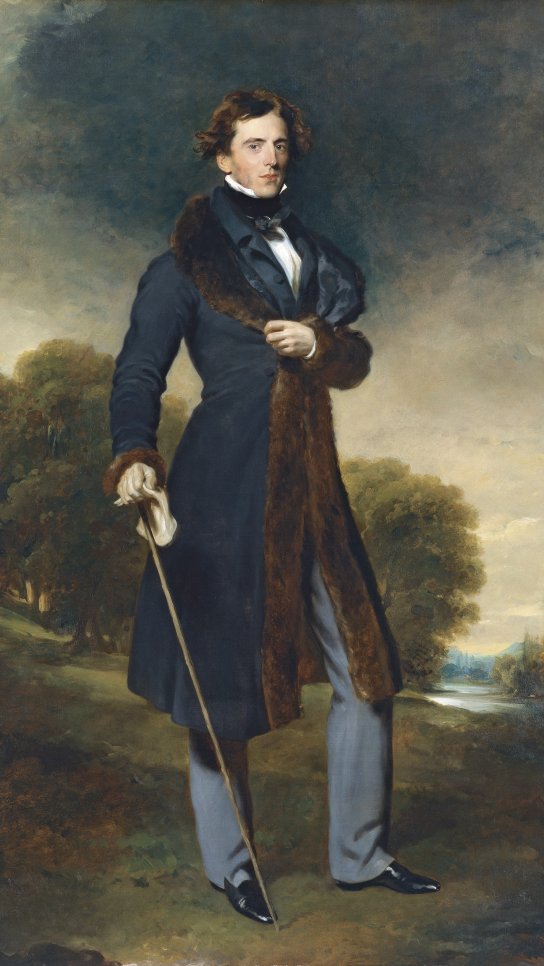

Portrait of David Lyon

Thomas Lawrence was the leading portrait artist to emerge from the English school in the 19th century. Already at 21 years of age Lawrence was employed by monarchs and in 1794 was chosen to be a member of the Royal Academy.

The Portrait of David Lyon is an exemplary work of the highest quality finished during the last stage of the painter’s career. The artist placed the sitter in a broad, open, and tranquil environment giving him an air of distinction and elegance through his upright pose and formal dress.

The position of the subject’s hand in the portrait epitomizes the essence of Dandyism. As a result of the skill developed by English tailors in working with wool, men’s clothing fitted more tightly. Tailors took great pride in seeing that the clothes they created did not show a single fold. In this portrait we can see the subject wearing «Brummel» trousers, a tailcoat and redingote as well as a fur-trimmed frock coat that is tapered at the waist, framing the figure in the way that a fashionable garment was supposed to. The finely polished shoes have a narrow tip. However, as the century progressed shoes would become wider.

The extravagance and the colour of men’s clothes had disappeared. A dandy could be recognised from the cut of his clothes and from the way he wore his tie: the collar of the stiff, starched shirt pointed upwards towards the cheeks, which was kept in place by a muslin handkerchief that was tied at the front with a knot. It is said that some dandies were able to spend an entire morning perfectly entertained fixing and arranging their neckties. They wore their hair short and uncombed and were clean-shaven, although on occasion they would sport sideburns and/ or a moustache.

The image of a gentleman did not undergo any major changes until the 20th century. The men’s suit had become so boring that by 1850 it ceased to appear in fashion magazines. It is only through changes in tailoring and painted portraits that we are able to track any developments of the suit during this period.

A Girl in Japanese Gown. The Kimono

In the paintings of Merritt Chase, the pioneer of American Impressionism, we can see evidence of the important shift that occurred in 1868 when Japan opened its port during the Meiji period. The Orient became a major source of inspiration and Japanese exoticism permeated art and culture.

The kimono (the literal meaning of which is «something to wear») soon became a hugely popular garment. It could be worn by both men and women. It consisted of a tight-fitting robe which opened at the front, and a voluminous waistband called an obi which was tied in a knot. The knots differed according to etiquette and social norms. The robe itself was made of a single piece of silk or cotton, and was adjusted to the body on the left by pulling the fabric over the right hand side of the body.

All sorts of oriental objects flooded into 19th century houses. As shown in this painting European women took to using such articles quite naturally. These new objects were made popular by fashion magazines and gave clothing a new air of modernity: Japanese style screens, bamboo furniture, exotic fabrics, ornaments and other articles such as fans, umbrellas, and porcelain objects were now widely sought after by the social and intellectual elite.

In A Girl in Japanese Gown we see Merrit Chase’s model looking at Japanese prints. Japanese artists caused quite a stir when they exhibited in Paris, especially amongst painters such as Monet, Renoir, Degas and Gauguin, as can be seen in the portrait that Monet painted of his wife wearing a kimono, or the poster which Toulouse- Lautrec prepared for the Moulin Rouge with its distinctive Japanese influence.

In the same room we can also see the Portrait of Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland by John Singer Sargent. The artist immortalized numerous models of the upper classes in Paris and London. The painting’s subject was one of the most radiant models of La Belle Époque in London at that time. Modern and confident, she rejects the typical fashion of the constricted waist and abandons the frills in favour of a new, fresh curvaceous look in which her bust is emphasised. The bell shaped dress cascades to the floor, and the brightly coloured printed fabric was particularly popular at that time.

Continues on the first floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Horsewoman, Full-Face (L'Amazone)

This work belongs to an unfinished series of the four seasons that Manet painted during the last years of his life on request of what was then the Ministry of Fine Art. The artist accepted this commission in a state of ill health, and only managed to completely finish the first in the series, Spring. The Horsewoman was most likely intended to represent summer. Manet focused his attention on the wardrobe of his subjects, given that at this time fashion was the key to modernity (according to Baudelaire). The young Henriette Chabot, the daughter of a bookseller friend, is seen here wearing an extremely elegant dark ensemble. The artist’s impeccable technique in working with dark hues can really be appreciated here.

It was during this period that sportswear first appeared. Special clothing was designed specifically for tennis, cycling and riding. The end of the 1890s would see the (for those times) scandalous arrival of trouser-skirt, short baggy trousers that were otherwise known as bloomers.

The passion for riding of so many women was reflected in fashion magazines of the time. They clearly show how masculine fashion influenced women’s fashion, but only up to the waistline. A woman’s typical attire consisted of a top hat held in place by a chin strap, a man’s jacket and vest, and an enormously voluminous skirt which almost touched the ground, making it impossible to dismount from the horse without the assistance of a stable hand.

Women’s sports clothes were heavy and dark and were inspired by men’s jackets. The woman seen here in the painting is wearing a slim, tight-fitting jacket; the starched white coloured shirt fastens with a golden broach, a counterpoint to the otherwise stark, masculine appearance. The outfit is adorned with a top hat, under which the hair is held together tightly in a bun. In her hand the rider carries a whip firmly in a long leather glove that is finished with twenty buttons.

In the same room we find Berthe Morisot’s The Cheval Glass. Aside from being Manet’s sister-in-law, Morisot was one of the founders of French Impressionism and actively participated in the group’s exhibitions. This work, first exhibited in 1877, represents the world of feminine feeling, a recurring subject throughout the entire collection of her works. A coy, coquettish woman is seen preparing for the evening as she looks into her mirror, fastening and adjusting her corset. This garment is of course associated with feminine beauty, flirtatiousness, and the duty to remain slim as dictated by the norms of fashion. This particular article of clothing had both its advocates and detractors. Various studies of the period reveal that the use of the corset was associated with what were then new physical problems such as the dislocation of the womb. Despite its dubious reputation, one of the most profitable businesses at the time was corsetry for bridal gowns. At the end of the day, these corsets would go on to influence the bustiers of Christian Dior and Jean Paul Gautier.

At the Milliner's

Degas came from a wealthy family. Early on, he opted to give up his law studies and dedicate himself completely to painting. As an artist he was always associated with the Impressionists, even though he considered himself to be a realist painter. Throughout his career he was fascinated by the female universe, by fashion in particular, and this would lead him to immerse himself in the world of Parisian couture. He would often visit boutiques in the company of his female friends.

From this socially minded point of view Impressionism was the art movement most associated with the ever-growing wellbeing of the middle class. The young bourgeoisie of Paris were the subjects of his paintings, and in an attempt to make the most of their ample free time, they became slaves to fashion.

With the advent of industrialization and mass production, sophisticated garments became more and more accessible to a wider segment of the population.

This is the first piece in a series that was dedicated to the hat shops of Paris. When it was first shown in public, it caused uproar due to the inclusion of pieces made of silk, feathers, straw and other materials normally associated with the ‘common man’. The forms and colour palette of the hats allowed the artist to show his skill in using colours, and his profound understanding of textures.

The hat shops were located on Paris’ most elegant streets, and these same streets were in turn depicted on canvas. One of these is Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain by Camille Pissarro, which is on display in the same room.

In the painting we can see two different types of straw hats: the wide-brimmed hat adorned with flowers and feathers commonly used to shade oneself from the sun whilst strolling through the garden, and a bonnet, held in place with a chin flap, which completely shut off any peripheral vision. These designs were influenced by the commonly-used headwear of past centuries.

The parasol began to be used as early as 1830. From then on and for almost a century afterwards, parasols were indispensable for women. They lent an air of elegance, not only because of the richness and variety of the materials from which they were made, but because of the particular way in which they were carried. Throughout the 19th century it was considered elegant to use them regularly. Together with the fan, gloves and the handkerchief, the parasol had its very own language.

Another example in the previous room, Woman with a Parasol in a Garden by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, illustrates the importance of the parasol for women.

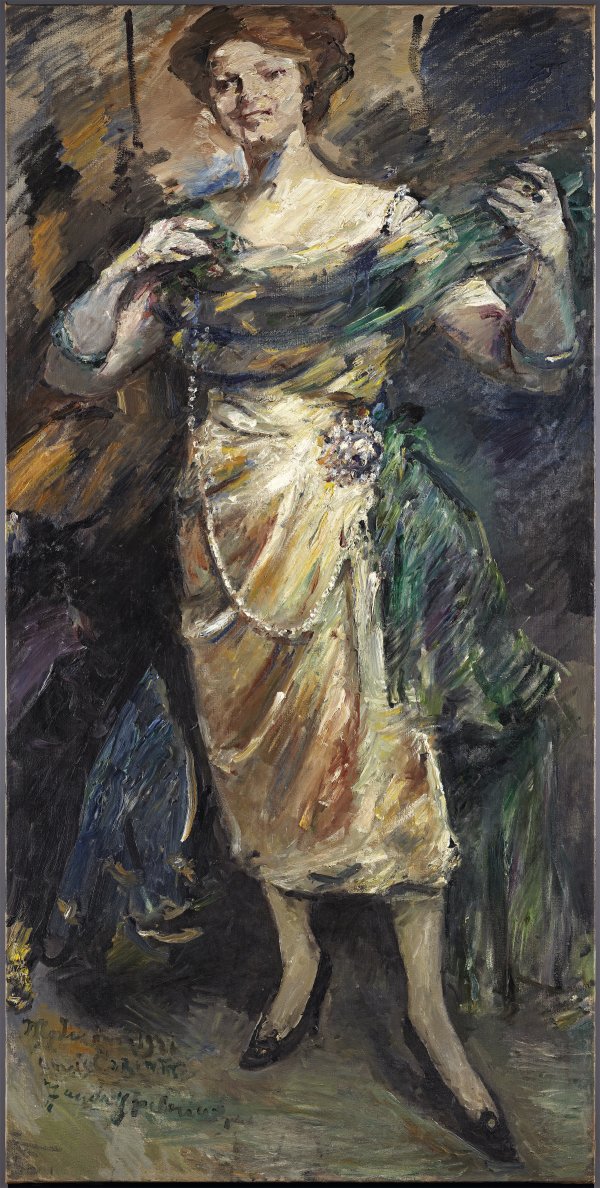

Fashion Show

Lovis Corinth was a German artist who fell under the spell of the impressionists and travelled to Paris. Upon his return to Germany he was awarded a professorship at the Berlin Academy. Fashion Show was painted in Berlin four years before his death.

Fashion shows began as early as 1800 by the couture houses. At the beginning of the 20th century Paul Poiret first created the modern female figure in Paris with rigid, straight lines and skin-coloured stockings, rejecting the use of the corset.

Poiret, was also a pioneer in that he was the first to launch his own perfume and to go on tours to promote his designs, for which he employed nine catwalk models. He even went so far as to design a suit, from start to finish, scissors and fabric in hand, in front of a live audience.

This painting captures a fashion show in progress: a model’s pose, covering her upper body with a scarf. The tubular dress made of yellow silk almost reaches her ankles. The tapering at the waist, which is characteristic of this particular decade, gives the body a cylindrical shape. In the course of just a few years a woman’s outfit went from weighing three kilos to only 900 grams. Once corsets were no longer worn the décolleté was fairly modest until the advent of the bra, when it was fashionable to accentuate and shape the volume of the bust.

The revolution truly began in 1925 with the appearance of the short skirt. The archbishop of Naples even went so far as to insinuate that the earthquake suffered at Amalfi was a direct result of God’s wrath brought on by skirts that did not cover more than the knees. In Utah there was even a law stating that any woman wearing a skirt shorter than three inches above the ankles would be fined and punished. In Ohio no woman over the age of fourteen was allowed to wear a skirt that did not reach her feet.

These measures were all, of course, completely in vain, and posed no great obstacle in the path towards emancipation. During les années folles women abandoned the home deciding to lead a more active social life. It was a decade filled with dance and exuberance - the decade of the Charleston. The female shape became more rectangular, with a dropped waist – the leitmotif for fashion design.

Inevitably with the great crash in 1929 came the introduction of new cheaper fabrics. In turn this allowed greater ease of movement and allowed women to take part in athletic activities more easily. Synthetic materials became more widespread and in 1933 the first pair of shorts appeared on the tennis courts. This was quickly followed by the disappearance of stockings at Wimbledon, much to the horror of the spectators.

The Smoker (Frank Haviland)

The Smoker was painted in ceret, a place in the French Pyrenees that had acquired the reputation of the «Mecca of Cubism» because Juan Gris’ stay there had coincided with that of Picasso’s, to whom the former referred to as «maestro.» The geometric defragmentation seen here evokes Picasso’s series of Cabezas (heads) painted in the same year.

Thanks to the preservation of a preliminary sketch that included a dedication, it is widely believed that this may be a portrait of Frank Haviland. Haviland was a rich American and friend of the Steins who had just recently restored a monastery in Ceret where he had an important collection of African art in storage.

Upon analysing the angular fragments on the canvas and rearranging them mentally, we discover the image of a man wearing a smoking jacket and a top hat puffing away on a cigar.

This type of suit had originated in Great Britain in the 19th century, and was initially used specifically for smoking before being considered a staple piece of men’s clothing. This formal attire was normally made out of black fabric, with satin detailing on the jacket and trousers. Gentlemen would wear this particular jacket, their so-called smoking jacket, after dinner, instead of wearing their frock coats to avoid them getting smoky as this might annoy their female companions.

Very soon after this the Fumoir or smoking lounge appeared, a private place where men could get together to smoke, an activity that at the time was associated with luxury and exclusivity. Smoking tobacco had become fashionable after the conquest of the Americas, but at this time smoking cigarettes had become fashionable thanks to a massive wave of imported cigarettes from Turkey.

Women took up smoking in 1925, and as a result the smoking jacket ceased to be exclusively for men. In the 1930s the main trendsetters were models. No woman, with the exception of Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel, had been so bold as to sport such a manly outfit. As fashion photographer Helmut Newton had noted there is nothing more sensual than a tall, svelte and strong woman walking around in a pair of high heels whilst wearing a smoking jacket borrowed from a man’s wardrobe.

To this day women’s smoking jackets are still considered to be stylish, especially since 1966 when Yves Saint-Laurent redesigned the traditionally male garment into something with a distinctive feminine touch. Over time the piece has become timeless - a classic piece in the fashionable woman’s wardrobe.

Simultaneous Dresses (Three Women, Forms, Colours)

Fashion, as with other forms of visual expression, was affected by the experimental tendencies of the avant-garde at the beginning of the 20th century. It was during this period that a concentrated effort was made for fashion to be recognized as art.

The Delaunays as a couple were pioneers of abstract art and claimed that the colour in painting was the generator of shapes and movement. They formulated the concept of Simultaneism based on the dynamics and contrasts of colour. Although Sonia did have success as a painter, her major contribution was in the world of decorative arts and textile design

She worked with hand printed fabrics and carpets, created designs for curtains, umbrellas, furniture, cushions and lamps. She was immensely creative and she left her mark on fashion as well as interior decoration. The colour combinations she used broke the traditional mould, and by using a mix of different fabrics with varied textures she further contributed to this breakthrough. In a magazine in 1913 she wrote: “I want to create something new and modern where the colour leaps out of the frame”.

When the First World War broke out it caught the Delaunays completely off guard while they were away on a summer holiday in Spain. In 1918, they settled in Madrid where they would stay until 1921. They opened their own boutique near Calle Serrano called Casa Sonia. It was a roaring success, and they went on to repeat the same formula in Bilbao, San Sebastian and Barcelona. During this time they worked together with the Diaghilev ballet company, with Sonia designing the wardrobe and Robert the stage-sets. The Hotel Claridge in Madrid was the venue for many of their fashion shows.

In 1921, they returned to Paris where they created the famous Simultaneous Boutique, a hybrid space that was part art gallery and part clothing shop. This new concept, as Sonia had imagined it, was in line with the changing, turbulent social climate of the time.

Looking at the painting we see the models wearing simultaneous style dresses in vivacious prints. This type of garment was, in reality, a work of art even though it was not on canvas. In 1913 Sonia designed her first simultaneous dress, which was soon followed by her poem-dress a few years later. The women who wore Sonia’s designs were living paintings, it was art on the female body, three-dimensional and it moved. Sonia met with resounding success in dressing fashionable actresses such as Gloria Swanson.

Brave, daring and visionary, Sonia Delaunay would go on to design prints used for automobiles by Citroën, and would be the first woman to see her paintings exhibited in the Louvre Museum during her lifetime.

New York City, 3 (unfinished)

In the year 1938, as the nazis were approaching, Piet Mondrian abandoned Paris and moved to London. By 1940 he was living in New York, where he would live out the remaining years of his life. Paris fell, but fashion survived despite the scarcity of fabrics, restricted manufacturing capacity and manpower.

In the United States the war did not have as great an impact as in Europe and fashion evolved rapidly, which to a significant extent was due to the film industry. In 1944 a dress worn by Ginger Rogers in the film Lady in the Dark was labelled the most expensive dress in the world at the time, costing more than $35,000.

Mondrian fell under the spell of American culture, jazz, boogie-woogie, its dynamic metropolitan cities and the skyscrapers of Manhattan. His painting became less rigid as he gained freedom and rhythm as can be seen in New York City 3, painted a few years before his death.

At this time, thanks to the common sense of designers such as Coco Chanel, fashion centred around simplicity and functionality. Her no-frills designs reflect the geometric paintings of Mondrian as well as the pure lines Le Corbusier’s architecture. The legendary Chanel Nº 5 bottle itself incorporates all of her principles: design, reduced to a simple geometric form and number conveying a message of modernity. The essence of her style went on to influence the next generation, including Christian Dior and his disciple Yves Saint Laurent.

Mondrian’s abstract compositions, with their straight, simple lines would also inspire Yves Saint Laurent’s legendary 1965 collection, a huge commercial success and one that was copied ad nauseum. The entire world applauded these creations that went beyond the previously established boundaries that lay between different artistic genres. Throughout their careers great designers would talk about their collections in the same way that Van Gogh, Matisse and Picasso had done about their paintings.

The idea of design and printed fabrics as works of art remains very much alive in the creations of current designers. Today, fashion is exhibited in museums and renowned fashion houses seek out artists who are capable of creating clothes that are real works of art.

Quappi in Pink Jumper

This room brings together a series of portraits of modern women whose personalities are reflected. Through what they are wearing. This inter-war period saw the birth of a new style of woman.

The new feminine ideal was androgynous and women made concerted efforts to appear masculine. All curves were hidden. Breasts were covered up completely and hips were smoothed out as the woman entered the work force. Neat, short hairstyles were the fashion now. These later progressed to styles, such as the garçonne, that could be considered almost boyish, brought on perhaps by Victor Margueritte’s controversial Garçonne (1922), which tells the tale of a young woman’s struggle to break the chains of social norms and to lead her own independent life. These new hairstyles followed the head’s natural contours and were highlighted by the cloche style hat that was so fashionable at that time.

In Paris various fashion houses were forced to close upon the arrival of new female talent brimming with revolutionary ideas, such as Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli. These two rivals were more than just designers; they were both at the forefront of a new artistic movement, and were cohorts of the most important intellectuals of the time. Schiaparelli’s designs were influenced by surrealists such as Salvador Dali and Alberto Giacommetti. Of particular note were her shoe hats. The Italian designer opened twenty-six workshops, with more than two thousand employees. In 1930 alone, it is estimated that her boutique turned over 20 million francs per year.

This remarkable painting is a magnificent example of Max Beckmann’s style. The portrait was exhibited in New York only once in 1938. In 1925 Quappi became his second (and final) wife. Work on the piece began in 1932 and was completed in 1934. Beckmann altered not only the date but also Quappi’s expression, making her smile much more comical to reflect the couple’s thoughts and worries of the impending Nazi rise to power.

In the painting we see Quappi the seductress; she has applied makeup to her cheeks and her lips, has plucked her eyebrows and is dressed in a fine tailored two-piece suit and v-neck pink sweater, which had been deemed as unhealthy by doctors and had ironically come to be known as the «pneumonia blouse».

""Sometimes all Max needs for inspiration for a painting of me is a piece of clothing"", writes Matilde Beckmann in her memoirs. This time it was a sweater and a pink turban that she had bought herself in Berlin. Throughout Max’s career he would paint more than fifty portraits of his wife. This piece was known as The American, named after the sensually posed, modern and sophisticated woman it depicts.

In the same room we find portraits of other modern women who lived independently of their husbands and wore short skirts and synthetic stockings, such as Karl Hubbuch’s Twice Hilde II. There are also portraits of men that show the almost negligible evolution of the formal suit, the undisputed staple in every man’s wardrobe. The only part of the suit that changed over time is the jacket: double breasted, straight, and with a waistcoat as can be seen in Christian Schad’s Portrait of Dr. Haustein and Otto Dix’s Hugo Erfurth with Dog.

Tour resources

The order of the works in this pdf may differ from the recommended order.