Original idea by Blanca Ugarte. Adapted by Teresa de la Vega

In addition to being an essential source of nourishment, food is also an object used in cult worship, a sign of wealth, a social ritual and a source of shared pleasure that involves all the senses and feeds the spirit. Given that, as the well known saying has it, “we eat more with our eyes than with our mouths”, the art of cookery, which involves creativity and colour in a way comparable to painting, has enormous visual appeal. As in an alchemist’s laboratory and surrounded by flasks, jars, paintbrushes and spatulas, both the cook and the artist transform their primary materials — saffron, berries, walnut and linseed oil, casein, fish tail, vinegar and egg white — into a creation that marks the transition from nature to culture through the opposition of the raw and the cooked.

Through this gastronomic survey the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection aims to satisfy visitors’ appetites, tempting your palate and feasting your eye.

Tour artworks

Jan van Kessel III (attributed to)

View of the Carrera de San Jerónimo and Paseo del Prado with a Procession of Carriages

HALL

Our gastronomic survey ends with a view of the junction between the Carrera de San Jerónimo and the Paseo del Prado, which is the location of the Museo Thyssen- Bornemisza today. The view of this part of Madrid reflects the way it looked during the reign of Charles II. It was a meeting place for the elite members of the capital’s society but also for the working classes. People gathered to see and be seen, to have picnics, take part in a range of festivities and celebrations and exchange news.

Fountains and water sellers were common sights on Madrid’s streets before houses had individual water supplies. According to a Treatise on Water of 1637 “one of the great virtues of the Spanish is that they drink a lot of water as they are not as enthusiastic about wine as other Europeans.”

If you look carefully at this painting you will also see a churrera or seller of fried dough strips. Known as “fruits of the frying pan”, these sweetmeats originated in the Arab world. They became extremely popular in Spain and also spread to South America. The strolling vendors who sold them are no longer to be seen on the streets of Madrid but their image in this painting evokes a rich gastronomic heritage which, like Spain’s artistic patrimony, is an inalienable cultural treasure that should be preserved and appreciated.

Master of the Virgo inter Virgines (follower of the)

The Last Supper

Not on display

This scene depicts the last supper, during which the institution of the Eucharist forged a New Alliance between God and man. Christ, with Saint John resting on his lap, gives Judas the bread dipped in wine and thus points out the person who will betray him just a few hours later.

The Jewish festival of the Passover or Pesah commemorates the liberation of the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. The word means “leap”, referring to God “passing over the houses of the people of Israel”, who painted their door jambs and lintels with lamb’s blood to save their first-born children from the plague that would decimate the Egyptians. Food plays a particularly important role in the celebration of this festival as it commemorates the experiences of slavery, exodus and liberation.

The Bible does not provide details on the food at the Last Supper as the Gospels only refer to the bread and wine that was transformed into spiritual nourishment, signifying the path to eternal life. It can, however, be assumed that the empty platter on the table in this scene had been used for a lamb, which was one of the foodstuffs eaten during this Jewish festival and prefigures the sacrifice of Christ who offered himself up in order to save mankind, according to the Christian interpretation. In some Renaissance paintings, however, we encounter various curious alternatives: in one of the panels for the Maestà in Siena cathedral Duccio di Buoninsegna, for example, depicted a suckling pig, which was an animal considered impure according to Mosaic law; Zanino di Pietro painted river crabs in a fresco of Saint George in San Polo di Piave; while in the most celebrated Last Supper in the history of art, Leonardo da Vinci depicted a plate with what seems to be an eel, which were also creatures forbidden in the Judaic tradition. The inclusion of these dishes may perhaps constitute an allusion to the Christian rejection of the Judaic distinction between pure and impure foods.

Paris Bordone

Portrait of a Young Woman

ROOM 6

The woman depicted here by paris Bordone holds a monkey by a chain, an animal traditionally associated with the sense of taste and one that became an emblem of greed. Allegories of this type, which became extremely popular during the Mannerist and Baroque periods, often had an ambiguous meaning given that the senses were considered the means to acquire knowledge but also an encouragement to sin.

The opulent beauty of the model suggests a metaphorical association between food and eroticism, reflecting Terence’s maxim sine Cerere et Baco friget Venus, meaning “Without Ceres and Bacchus, Venus freezes”. The secular association of sensuality and food is also echoed in popular beliefs. Thus certain types of pasta are said to have anthropomorphic origins: tagliatelle, for example, were traditionally invented by a cook in imitation of the blonde hair of Lucrezia Borgia, while the original tortellini were modelled on the navel of an obliging lady.

Christoph Amberger

Portrait of Matthäus Schwarz

ROOM 9

The sitter, Matthäus Schwarz, worked in the service of the powerful Fugger family and wrote a number of treatises on accountancy. He also wrote a fascinating work known as the Trachtenbuch that is now in the Herzog Anton Ulrich Museum in Brunswick. This manuscript, which is essentially biographical, includes 137 illustrations of the most important items of clothing that Schwarz owned during the course of his lifetime. It is an extremely important document as it offers highly valuable information on male dress of this period. One of the illustrations depicts Schwarz naked, aged 29, accompanied by an annotation that reads “I have got fat and spread out."

Schwarz’s concern for his appearance reached its height with the celebration of the Imperial Diet (Reichstag in German) in Augsburg in 1530, which was presided over by the Archduke Ferdinand I of Austria and his brother, the Emperor Charles V. Schwarz commissioned three expensive suits for the occasion and managed to lose weight. In other words, he went on a diet for the Diet.

By the time he posed for this portrait Schwarz had got fat again and his excessive enthusiasm for eating may in fact have been the cause of his subsequent apoplexy. On the window ledge we see a glass of red wine, which could be a reference to his nature as a bon vivant or to the origins of his family’s fortune in the wine trade. There is also a sheet of paper with details about the sitter in the form of a calendar and his astrological information. Another unusual element is worth noting: Schwarz’s horoscope written in gold letters on the sky.

Jan Gossaert

Adam and Eve

ROOM 10

All human history attests That happiness for man — the hungry sinner! - Since Eve ate apples, much depends on dinner.

(Lord Byron) Since the moment when Adam and Eve sampled the Forbidden Fruit in the Garden of Eden, food has played an important role in biblical and sacred literature. In fact, the Bible does not state that the Fruit was an apple and as a result artists have on occasions preferred to depict it as an apricot, a peach or a fig. Genesis does, however, mention fig leaves in connection with the Fall as a symbol of shame for the sin committed.

In general, the apple was selected as the fruit in question for reasons of semantic similarity (apple in Latin is malum, which is similar to mal) and due to its identification with beauty and pleasure in the classical world. The latter association is reflected in a number of myths including the Garden of the Hesperides and the Judgment of Paris, an episode to which the basket of apples in Pietro Longhi’s painting The Tickle may refer (on display in Room 18).

Anonymous Venetian artist

The Last Supper

Not on display

In his Dictionary of cooking Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870) asked: “Do we in fact owe Titian’s masterpieces to spices. I am tempted to think this might be the case.” The brilliant chromatic range of the Venetian artists made its appearance in a city dominated by the constantly changing glint of light on water, together with the gleam of mosaics and silks from the Orient. In comparison with the frugal simplicity of The Last Supper that we looked at earlier, on display in Room 3, this canvas depicts a sumptuous banquet in a sophisticated, theatrical setting in which we see a variety of secular elements such as the servants and the domestic animals that took full advantage of morsels of food thrown on the floor.

Humanist culture, in which artists’ aspirations focused on greater intellectual recognition and social status, gave rise to the appearance of a number of famous cooks and authors of treatises on food such as Cervio, Platina, Scappi and Messisburgo, all of whom recommended that food should be visually agreeable and with a bel colore. In addition, in his writings the painter and theoretician Federico Zuccaro drew a parallel between the noble art of painting and the organisation of a banquet, presided over by discernment, good taste, variety and abundance.

Of equal importance to the food itself was its presentation on silver or maiolica plates, which functioned to emphasise its appeal. In addition, there were the trionfi da tavola, “ornate, temporary decorations made of sugar, marzipan and butter” that were designed by celebrated artists such as Benvenuto Cellini, Giulio Romano, Giambologna and Pietro Tacca. According to one account, during the plague of 1630 the sculptor Tacca (who produced the statue of Philip IV in the Plaza de Oriente, Madrid) melted the sugar of his creations and mixed it with wine in order to fortify his assistants and avoid them fleeing with his studio secrets.

During the Renaissance the pleasures of the table became inextricably linked to sensibility and refinement. Banquets during this period not only satisfied hunger and conveyed the host’s social status; they also offered an excuse for guests to display their good manners and eloquence. Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) is better known as an architect and theoretician but he also wrote Intercenales, which is a collection of short texts designed to be read out during a banquet.

In 1494 a Milanese pilgrim lamented the frugality of a dinner that he attended on his way through Venice: “In my opinion, the Venetians make do with the sustenance provided by art.” There is no doubt that the genius of Venice’s artists has sustained its citizens, who in the 20th century paid homage to their painters by naming dishes after them: carpaccio for thin slivers of raw meat with parmesan, and a bellini for a cocktail, reflecting the colours used by these painters, whose works you can see in Room 7.

Claude Lorraine

Pastoral Landscape with the Flight into Egypt

Not on display

The special relationship between artists and cookery over the centuries is reflected in the traditional attribution to Claude Lorrain of the invention of millefeuille pastry.

Born around 1604 or 1605 in the region of Lorrain, Claude Gellée revealed his talents for art at an early age. He was, however, from a poor family and his biographies state that he was obliged to divide his time between painting and working in the village bakery. Eventually he was able to devote himself fully to art, specialising in refined, arcadian landscapes. Claude was not the only artist to devote time to food.

The painter Andrea del Sarto, for example, reproduced the Florence Baptistery in sausages and cheese as a table decoration, while according to some accounts the architect Bernardo Buontalenti invented ice cream while Cesare Ripa, the author of a highly influential book on emblems entitled the Iconologia, is referred to in the early literature as a trinciante or meat carver in the service of a cardinal.

Hendrick ter Brugghen

Esau selling His Birthright

ROOM 20

Genesis recounts that jacob, later known as Israel, “he who fights with God”, purchased his brother Esau’s birthright for a plate of lentils. According to tradition Jacob was the second of the two twins to be born to Isaac and Rebecca. During her pregnancy the boys fought in their mother’s womb. She received the divine message that two nations were forming within her and that the one represented by the elder son would serve the younger’s. Rebecca always favoured Jacob while Isaac revealed a preference for Esau.

One day Esau returned hungry from hunting and asked his brother Jacob for some of the lentil stew that he was eating. On his mother’s advice Jacob asked for Esau’s birthright in return for the lentils, to which his brother agreed, thus scorning the spiritual benefits that the position of first-born implied in favour of momentary, material benefit. This story is the origin of the popular saying that a person has sold his honour for “a handful of beans”. The plate of olives that the boys’ elderly mother holds has been interpreted as a sign of divine approval, as in the Old Testament the olive was one of the gifts of the Promi-sed Land while its oil was a key element in the mass.

Another possible interpretation of this episode is that it revolves around the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to agricultural ones, symbolised by the opposition between the dead game brought back from the hunt by Esau and Jacob’s lentils. In addition, it is interesting to note that the lentils, which are rich in proteins, are accompanied here by a lemon, as it has been proved that the iron in lentils is more easily absorbed if accompanied by Vitamin C, to be found, for example, in citrus fruits.

The soft light from the candle helps to create a holy atmosphere and also reflects the enormous interest in effects of artificial light on the part of northern artists of this period. This is also evident in another work on display in this room, The Supper at Emmaus (ca. 1633-39) by Matthias Stom, in which bread once again plays a crucial symbolic role.

Caesar van Everdingen

Vertumnus and Pomona

ROOM 20

In the Metamorphoses Ovid recounts how Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit trees, gardens and vegetable plots, showed no interest in men despite being desired by all the rural gods. Only Vertumnus, god of seasonal changes, truly loved her. In order to earn her trust he made use of a trick. Disguising himself as an old woman, he visited her to congratulate her on the fruit from her trees then passionately embraced her, revealing his true, resplendent face and thus capturing the young goddess’s heart.

This story, which was particularly popular in Dutch art, may involve a warning to young women to take care against the ruses of seduction. It may also imply a reflection on the illusionistic nature of painting.

At Pomona’s feet is the fruit that she has carefully grown, including citrus fruit, figs (which were the gift of Dionysus in Greek culture) and melons. While melons were an ancient fruit as they are mentioned in Egyptian texts, during the Renaissance a particularly sweet Armenian variety was planted in the papal orchards of Cantalupo near Rome. It is said that Pope Paul II died from indigestion brought on by melons and that Innocent XIII used them as cups for drinking port in order to bring out its aroma.

In the 17th century cantaloupe melons became highly appreciated in France and Italy where they were grown under glass to protect them from the weather and were watered with water sweetened with honey or sugar.

Emanuel de Witte

The Old Fish Market on the Dam, Amsterdam

ROOM 25

The 17th century was a period of notable prosperity in Holland with an unprecedented demand for works of art by the mercantile classes, who wished to see their ideals and lifestyle reflected in them. The abundance of foodstuffs depicted in busy market scenes celebrated the prevailing commercial boom that was the principal source of income of the wealthy classes. These paintings thus convey a sense of wellbeing seemingly intended to exorcise the spectre of hunger.

In De Witte’s scene a woman examines the merchandise before the attentive gaze of a hungry dog who may at any moment take a bite from one of the enormous fish with silvery scales from the North Sea. We also see a young girl touching the tail of another fish and a surprising detail in the presence of a stork, which the artist would include in subsequent paintings of this type.

Gabriel Metsu

The Cook

ROOM 25

A comparison of this work and the previous one by Emanuel de Witte reveals the polarity between the raw and the cooked, which is a key issue in anthropological research on cookery. The cook, depicted here in her work place, proudly displays the fruits of her labour. Her saucy gesture suggests that she is offering herself along with her roast. The artist, Gabriel Metsu, also specialised in domestic interiors, market scenes and taverns. He must have appreciated cooking, or perhaps the cook, as he repeated this subject on two other occasions.

Some scholars have seen an erotic reference in the cook’s ambiguous gesture, emphasised by the partridges hanging in the background, which are a traditional symbol also to be seen in two paintings on display in Room 9, The Nymph of the Fountain by Lucas Cranach the Elder, and Hercules at the Court of Omphale by Hans Cranach.

Jacob Lucasz. Ochtervelt

Oyster Eaters

ROOM 25

On display in the same gallery is Eating Oysters by Jacob Lucasz. Ochtervelt. Here the underlying association between sex and food, arising from their shared celebration of abundance and the pleasures of the senses, arouses the instincts of the figures.

Oysters, referred to as minnekruyden (herbs of love) by the Dutch poet Jacob Cats, can be interpreted symbolically given that in the same way that a person’s most intimate emotions remain hidden deeply within their psyche, the interior of the oyster is firmly protected by its valves.

Oysters became habitual elements in the game of love due to their supposedly aphrodisiac properties, as can be seen in another work in the Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, Interior with two Women and a Man drinking and eating Oysters by Pieter Hendricksz. de Hooch (Room B).

Willem Claesz. Heda

Still Life with Fruit Pie and various Objects

ROOM 21

During the golden age of dutch painting the still life broke away from religious and genre scenes and became an autonomous genre. In addition to its decorative character and virtuoso illusionism, the sophisticated settings of the works on display here (such as those by Willem Kalf, Willem van Aelst and Jan Jansz. van de Velde III) allude to the seduction of the exotic and to the taste for luxury of the affluent classes, whose tables abounded in the most highly prized ingredients as a consequence of the wealth generated by mercantile activities. These foodstuffs included meat pies, amber or ruby coloured wines in fine glasses painted to emphasise their decorative nature, citrus fruits from hot countries, and sugar (previously a rare commodity) in porcelain bowls.

There has been considerable debate as to whether there is an admonitory or moral message in these works, which can be linked to the type of painting known as a vanitas that was particularly widespread in the 17th century. The presence of watches, broken or tipped over glasses, dried fruit peel on the tablecloth and halfeaten food would thus refer to the inexorable passing of time that devours everything and to the futility of worldly pleasures. This notion, however, is paradoxical, as a rejection of earthly pleasures clearly coexists with the opulent indulgence prevailing in the residence of the upper middle classes.

Peeled lemons are frequently to be seen in Dutch still-life paintings, suggesting a variety of meanings. The spiral of the peel hanging over the edge of the table provokes a sense of precariousness, as does the protruding knife which bears the artist’s signature in this work. Another interpretation could be that the lemon’s pitted skin contains a fragrant interior, just as the perishable body houses an immortal soul. In addition, this fruit was a symbol of temperance and its juice was thought to counteract the effects of alcohol.

Juan van der Hamen y León

Still Life with Porcelain and Sweets

ROOM 21

In comparison to dutch still-life paintings with their informal arrangement of luxurious items that evokes a “masculine” world of overseas expansion and commercial success, the regular arrangement of the vessels and sweetmeats in this painting reflects a more homely, “female” environment of everyday foodstuffs in white and earth tones (ochre, orange) that look back to earlier tradition.

Van der Hamen’s still lifes, which are influenced by Sánchez Cotán’s compositions, are a model of simplicity. They are imbued with a pervasive tranquillity and a meditative mood that transforms the humble objects depicted in them. “God also walks among the cook pots”, to quote the famous words of Saint Theresa.

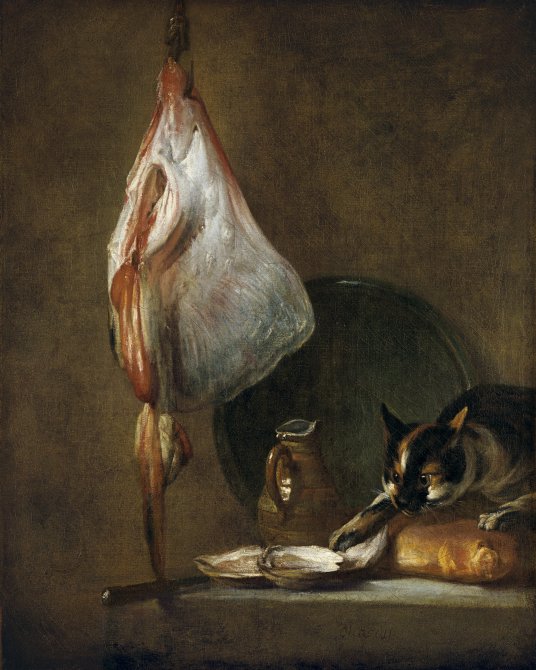

Jean Baptiste Siméon Chardin

Still-Life With Cat and Rayfish

ROOM 24

A faithful recorder of petit bourgeois life, Chardin (also represented in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection by another similar work "Still Life with a Cat and Fish" and a small still life on display in the previous room) transforms inanimate objects into living ones. He does so through the presence of the cat, the contrast between the dry fish and the fresh salmon and rayfish, and through his warm, “buttery” type of brushstroke.

Under a diagonal light, Chardin arranges the cooking implements on a sideboard, indicating that the foodstuffs are about to be prepared and seasoned with the black pepper in the mortar and with the vegetables that started to replace costly spices in the 18th century. Within the climate of the Enlightenment, French cooking acquired its own identity in a process that would lead it to become one of the most refined and sophisticated cuisines in the world.

After the Revolution, the restaurant became the new temple of gastronomy in which to sample refined dishes previously only available to the aristocracy. “Architecture is the most noble of the arts, while art’s most celestial manifestation is that of the pastry chef” affirmed Carême, one of the great geniuses of 19th century cookery and a chef notably influenced by painting in the visual quality of his creations.

Giacomo Balla

Patriotic Demonstration

Not on display

Red, white and green are the colours of the Italian flag and also the ingredients of a pizza margherita (tomato, mozzarella and basil), which is said to have been created in June 1889 in honour of Queen Margaret of Savoy by a chef in the Pizzeria Brandi in Naples.

The subject of Balla’s painting has nothing to do with cookery as it is one of a series on the demonstrations held in Rome calling for Italy’s involvement in World War I, a decision finally taken in May 1915. We should bear in mind, however, that the provocative Futurists waved the banner of revolution in all areas of life. The year 1930 saw the publication of the Futurist cookery manifestation in which they expressed their dislike of pasta, which they considered to have lowered Italians to the most basic level.

The Futurists opened an experimental restaurant called Tavern of the Holy Palette. It served dishes such as “intuitive antipasti”, “Fiat chicken”, in which the chicken was cooked on ball-bearings that gave it a taste of aluminium, “Alaska Salmon cooked with Sunbeam and Mars sauce”, “edible Meteorites” and “visual meat”, all only apt for outlandish palates.

All the senses were involved in the celebration of their “Aero-banquet”, in which various perfumes reached the table via a ventilator and announced each dish, the eating of which was accompanied by poetry and music. The sense of touch was also evoked as diners had to touch pieces of silk and velvet or strips of sandpaper in order to participate in a multi-sensory aesthetic experience.

Richard Estes

Nedick's

ROOM J

The Nedick’s chain was launched in New York in the 1920s and soon became one of the city’s icons. This period saw a radical shift in eating habits as a result of changes in food production and distribution. These in turn arose from complex social phenomena such as industrialisation, the widespread incorporation of women into the workforce, an obsession with hygiene, a rabid consumer culture and the fact that people were not allowed to take much time off work, leading office workers in the city centre to eat as quickly as possible.

It was Nedick’s that offered these workers a complete menu of hamburger, coca-cola and chips in seconds. It was a pioneer in fast food until it was overtaken by its rival McDonald’s, which opened its first self-service restaurant in 1937 in Pasadena, California, in response to the inhabitants’ dependence on the car. These chains were joined many years later by ones focusing on “ethnic” food: Neapolitan pizzas, Mexican tacos and Japanese ramen, all essentially the same and devoid of personality in their effort to avoid surprises.

Nonetheless, it was not only the price, speed and functionality that contributed to the success of these chains. The transgressive pleasure of eating with one’s hands, the soft or crunchy textures and the sweet-and-sour taste of the sauces reproduce pleasurable oral and taste sensations from our childhoods which is when our palate develops.