By Elena Rodríguez and Begoña de la Riva

During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the work of the goldsmith occupied an important place in public life, as opposed to its traditional status as inferior to other fields of art such as painting and architecture.

In these two periods, magical and medicinal properties were attributed to gems and minerals. These qualities, cited in ancient texts such as Pliny the Elder’s Natural History and the works of Aristotle, were compiled in so-called “lapidaries” by medieval authors like St. Isidore, St. Albert Magnus — inspired by the writings of Avicenna —, Marbod and Alfonso X the Wise, among others. Some referred to the magical and medical properties of stones, while others explained their astrological connections or religious connotations. They became manuals for the use of stones for therapeutic purposes and circulated among apothecaries, doctors, jewellers and aficionados throughout Europe.

Jewels also provided clues to the wearer’s social and economic status. They could symbolize belonging to a certain family, religious or military group or allude to the moral virtues of the individual in question.

This close relationship between jewellery and the social or ideological position of the group or individual who owns it would find a fertile breeding ground among the Renaissance elite. In an extremely hierarchical society like that of the 16th century, the monarch’s appearances, whether physical or in the form of artistic images, were understood as representations of the power of State to both his subjects and other powers. When it wasn’t the monarch who was travelling, but rather his ambassadors and diplomats, they were also required to dazzle everyone with their profusion of jewellery as a symbol of the country’s wealth. This was part of their job and in the case of painting, the more skilled the artist at depicting these pieces in great detail as a symbol of inherited authority and privileges, the more revered he was. The case of the German painter Hans Holbein the Younger is paradigmatic in this regard, for not only was he admired for his ability to faithfully reproduce reality, but he also personally designed jewellery for the House of Tudor.

Henry VIII was passionate about jewellery and a regular client of goldsmiths. Renaissance princes were the image of the perfect gentleman and their habits were therefore imitated by the rest of society. As a result, there was such a huge demand for jewellery in Great Britain that many artisans went to the isles in search of work. Many others, however, had fled there to escape religious persecution. In addition, following his rupture with Rome, the King’s treasury was also augmented considerably following the dissolution of many monasteries and the confiscation of ecclesiastical property. Moreover, when royal marriages dissolved the wives’ jewellery collections went into the royal coffers. Princess’ dowries helped local tastes in jewellery transcend borders when they were copied or reinterpreted in other countries. The same occurred with diplomatic missions, which were another way of spreading fashions and models.

This movement of objects and artisans makes it difficult to establish any national stylistic influences, save for the predominant Italian — in turn inspired by a new interest in the forms of Classical Antiquity — or the very attractive, exotic influence of decorative Islamic art, much to the taste of the great Hans Holbein.

Tour artworks

Hans Holbein the Younger

Portrait of Henry VIII of England

ROOM 5

The main piece of jewellery that appears in Portrait of Henry VIII of England (c. 1537) by Hans Holbein the Younger is a series of rubies mounted on solid gold decorated with acanthus leaves, which served to connect the openings of his slashed sleeves and doublet. The ruby had been one of the most prized precious stones since the Middle Ages. It was associated with the spiritual and protected its owner from any kind of evil influence. The jerkin, or leather jacket and gold fabric worn over the doublet, is adorned with gold buttons with a little stone in the centre.

His hat, with a large ostrich feather on it, is decorated with pearls held together by gold threads and precious stones, perhaps sapphires, set in gold just like the two rings that he is wearing on both of his index fingers. According to Marbod’s Lapidary, sapphires were apt only for kings’ fingers and protected against wounds, envy and fear; among many other virtues, it also helped the wearer be loved by God. Henry is also wearing a gold chain of links shaped like Solomonic columns interspersed with the letter H, his first initial. Gold symbolised the power of kings, popes and bishops as the temporary representatives of God on Earth. Hanging from this chain is a large round gold pendant decorated with acanthus leaves and a stone in the middle, surely another sapphire. Judging from its thickness it could be a locket, a medallion, a portrait or a watch. The pendant allowed greater stylistic freedom during the Renaissance as the ideal complement to opulent chains, as we can see in this portrait.

The rich clothing and jewellery that Henry is wearing are symbols of his privileged, representative position. They are part of the scenography characterized by frontality, aloofness, solemnity and monumentality that Hans Holbein uses to establish the character of a monarch who brought together in his person the powers of Church and State.

Garments and hats were symbols of power, magnificence and aloofness thanks to the presence of multiple jewels which were included on them as the occasion required. Jewels were an essential part of pieces of clothing, for they were sewn right onto the fabric. For each ceremony or public act, the monarch would wear a specific ensemble accompanied by a certain combination of jewels. Thus, royal houses and powerful families owned a great deal of jewellery which was combined in order to meet different needs.

This passion for adornment spread throughout society, with each social classes spending as much on ornaments as it could afford. Brooches, insignias and pendants were the most characteristic jewels of the Renaissance. Other fundamental pieces included rings, though few examples have survived in their original state, since most of them were reworked starting in the 17th century when the art of gem carving was perfected.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (Domenico Bigordi)

Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni

ROOM 5

In Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Portrait of Giovanna degli Albizzi Tornabuoni (1489-1490) the objects around the sitter allude to her refined tastes and pious nature, but they also support an ideology and give us information about her social status.

According to the revision of platonic and neo-platonic ideals carried out during the Renaissance, Good and Beauty are the paths to the most sublime category of all, Truth, which was associated with God in society of the period. The way to attain it is through intellectual love, the kind that has to do with the soul, for this is the state when human beings are the closest to God. In the Renaissance the woman is the beginning and the end of this sublime love, and her beauty is the measure of her moral virtues. There is, then, a relationship between physical and spiritual beauty. In the case of painting, the visual art par excellence, spiritual beauty is therefore replaced by physical beauty, making it a reflection — albeit imperfect — of divinity.

The cartellino on the right-hand side of the Ghirlandaio painting contains a fragment of an epigram by Martial that says: “Art, would that you could represent character and mind. There would be no more beautiful painting on earth”. The text alludes to the beauty of the young woman’s soul and puts spiritual beauty above physical beauty. Transferring the splendour of divine goodness to beauty through the Quattrocento ideal of female beauty — as in this portrait of Giovanna — becomes the goal of painting during this period.

Giovanna is wearing a black silk cord with a ruby pendant mounted in a gold setting with another stone above it, possibly a beryl, and three pearls below. On the niche behind her is a dragon-shaped gold brooch that contains another large ruby surrounded by three beryls and two pearls. In Renaissance society, each object or way of wearing an ornament or a garment denotes a certain social class. They are not only symbols of wealth, but also of class privileges. During this period, the bourgeoisie secured its status as a powerful class that sought to be equal to the aristocracy, often managing to surpass it in richness and influence. As for Giovanna, she was from a family of rich merchants called the Albizzi. They belonged to the powerful wool guild and were one of the oldest clans in Florence which came to hold the highest positions in the city’s institutions. The Tornabuoni, her husband’s family, were bankers related by marriage to the Medici and one of the latter’s most trusted allies.

The two abovementioned pieces of jewellery that appear in this portrait are symbols of her public life; that is, not only would Giovanna have worn them for the pleasure of adorning herself and enhancing her beauty — an attitude in keeping with the new humanist idea — but they also indicated the power and wealth of her social class. They are symbols that the rest of society knew exactly how to interpret, putting these families on a higher level. As in the portrait of Henry VIII, the ruby — the star gem in that painting — alludes once again to virtue, as it was associated with spirituality.

Both pieces were temporary gifts from the Tornabuoni — sophisticated humanists who were very fond of precious objects — to Giovanna upon her betrothal to Lorenzo, and she would have worn them at her wedding and throughout her married life. At that time if the wife were to die, custom dictated that these jewels had to be returned to the husband’s family, as occurred in this case. Brooches were usually worn fastened to clothing and in the hair, but if a loop was attached to the back, they could also be used as pendants.

Hanging from the top shelf of the niche on the right-hand side of the painting is a strand of coral beads that might be a rosary, finished off with gold threads. This would allude to the lady’s virtue, as coral was believed to have apotropaic properties like the ruby. It was also commonly used during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in necklaces and bracelets to protect against evil eye and prevent sterility in the women who wore them. Another one of the young woman’s virtues, her piety, is represented by the halfopen prayer book. Its dark tones make the gilded edges and clasps stand out.

The two ruby and pearl brooches and the lustrous coral rosary that accompany Giovanna emphasize not only her elegance, but also her spiritual purity by comparing it to the luminous quality of the jewels.

During the Renaissance precious stones were not very valuable on their own. Rather, they were elements that made up part of the overall design of a piece of jewellery, which was given priority over the gem itself. As Cellini said in his Treatise on Goldsmithing, it was important not to mount them either too low, or they would lose their appeal, or too high, else they would seem like “a different piece, separate from its ornaments”. Moreover, a thin sheet of metallic foil was usually placed under the stone to enhance its shine in the most suitable way depending on the type of foil used. There were four types of different-coloured foil, depending on the alloy of gold, silver and copper and how long they were exposed to the fire. (The shine of the metal, gold or silver that held the stone often eclipsed that of the gem, making it necessary to place a coloured paillon between the mount and the stone to enhance its colour). Another technique was to dye them, but this was only allowed — if done by a true professional — in the case of diamonds.

Plaques, small metal sculptures, objects for public or domestic liturgy, the decoration of clothing, metal accessories, household goods and other pieces were also made by goldsmiths. As for the profane pieces, so few have survived that it is hard to get a clear idea of all the objects that existed and the vast, diverse field that opened up to artists thanks to the constant demand for these representative, decorative or domestic pieces. Great masters were often called upon to make them, as is the case of Ghiberti, Andrea del Verrocchio, Antonio de Pollaiolo and Hans Holbein the Younger, which shows that for society of the period, metalworking was not considered a lesser art and that goldsmiths, painters, sculptors and architects worked very closely together throughout Europe. At the same time, there were clients from every strata of society who commissioned more traditional artisans to meet the huge, constant need to decorate great houses and their inhabitants as well as representative buildings of the municipal, royal and religious administrations. The demand for ornamentation by society of this period was much greater and dynamic than the number of surviving works would suggest.

The development of collecting in Europe led to a growing interest in discoveries of pieces from Antiquity as well as a taste for the rare, the extraordinary and the exotic. It also fuelled a strong demand for these small ancient pieces made of precious stones and metals among patrons with a Humanist background, such as Lorenzo the Magnificent, Francis I and Henry VIII. Due to this influence the design became — as in all art of the period — more naturalistic. Thanks to the education that these clients had received, they could identify each of the gems and all the qualities associated with them, making them expert clients. In fact, the three abovementioned patrons showed, from their youth, a professed taste for lavish adornments and there are many surviving examples from their collections. Goldsmiths would go from court to court, adapting to the personal tastes of each client. That is why now it is so difficult for us to know who made each piece or to talk about schools, though the influence from Italy made Italian art fashionable throughout the continent, tainting local styles.

In any case, we usually know nothing about most of the artists who made these magnificent, perfect jewels during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. Very few of them still exist, and the only surviving examples have undergone major modifications to adapt to the fashions of subsequent periods. We can only get a rough idea of their beauty, power and presence through drawings, inventories, descriptions and paintings.

Francesco del Cossa

Portrait of a Man with a Ring

ROOM 5

One exception is Francesco Francia, a painter and goldsmith from Bologna. One of the theories about the identity of the man depicted in Francesco del Cossa's Portrait of a Man with a Ring (1472-1477) is that could be Francia himself. Vasari refers to him as a very talented silversmith and a great master of the niello technique. He also mentions his skill at setting gems, but it was his work as a medallist that brought him the greatest fame and the genre where he excelled the most. In fact, Francia served as the master of Bologna’s mint until his death.

During this period artists were still craftsmen; thus, their union in what were known as guilds was essential to their integration in society and their contribution to the city’s economy. Even in the case of the most prestigious cases such as that of Ghiberti or Donatello, artistic freedom was tightly restricted by the client, who was the one decided the materials, payment and procedures. Artists did not have a guild of their own, but rather they belonged, according on their specialities, to other guilds.

In the mid-16th century Benvenuto Cellini would defend, in his Treatise on Goldsmithing, professional specialization as a way of attaining excellence, but in previous periods the opposite was normally true. The multifaceted skills and work of certain artists in different artistic fields somehow helped them resist the segregation of the arts into separate guilds.

Michael Pacher (follower of)

The Virgin and Child with Saint Margaret and Saint Catherine

ROOM 8

Goldsmiths belonged to the silk guild, which also included the goldbeaters, the gold spinners and the silversmiths. Many goldsmiths were also painters and sculptors and they were enlisted with designing fabrics. Their patterns were used in embroidery workshops of the period and on the clothing of the individuals who were portrayed in different works. In fact, they may have become a kind of catalogue of fabric designs that travelled all over Europe. In The Virgin and Child with Saints Margaret and Catherine (c. 1500), possibly by a disciple of Michael Pacher, we can see how the gold background has an etched vegetable pattern that matches the clothing of the Virgin and the two saints, which was most likely made using the stencilled sketch technique. The halos of the Virgin Mary and the Baby Jesus have a different design, also etched, which was probably drawn in beforehand with a compass.

This work brings together the themes of the Sacred Conversation, the Coronation of the Virgin and the mystic marriage of St. Catherine. In the composition we can also recognize St. Margaret, on the left, by the dragon lying at her feet and by the cross over which she is meditating. St. Catherine, on the right, is holding a book and the wheel of her martyrdom is at her feet.

Michael Pacher, a German painter and sculptor from the late 15th century, is the most important Late Gothic artist from the Alpine region. His work combines the monumentality and typical forms of German artists with the influence of Italian painting through artists such as Andrea Mantegna and Filippo Lippi. Yet the presence of gold in the background makes the work fall within a trend that was outdated for the period.

Over the course of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, gold was not only identified with the temporary power of monarchs granted to them by God, but was also fundamentally associated with sunlight, the source of life and the divine symbolism of light. God was light. The architecture of Gothic cathedrals reflected this symbolism and their huge stained glass windows illuminated by the sun were compared to jewels. They allowed the faithful to imagine the walls of Heavenly Jerusalem which were made of precious stones, befitting the holiness of the city of God. Thus, in the case of the visual arts the use of gold gave the piece a material, transcendental value.

Before the work was executed, the areas that were to gilded were marked during the preparation phase. The gilding began by making the gold leaf, a job done by goldbeaters which consisted of pounding coins with a hammer until they became extremely thin, lightweight sheets of gold.

This was followed by applying several layers of Armenian bole, which was regarded as the most suitable preparation for the subsequent burnishing of the gold due to its warm colour and smooth surface that stands out in slight relief. Once dry, the bole was also burnished with a linen cloth. Handling these sheets was a task that required tremendous care and skill due to the fragility and lightness of the metal. Today artists still use the same method, which consists of laying the gold leaf on a leather gilder’s cushion and cutting out a smaller piece using a straight-edged knife.

The piece of gold leaf is then picked up using a special gilding brush and placed over the bole, previously dampened with water and gesso. When the gold comes into contact with the water on the bole, it rapidly adheres to the surface. This process is then repeated, slightly overlapping the edges of the different sheets until the entire desired surface has been gilded. When it dries, the gold looks very flat with an opaque yellow colour. To achieve the effect of solid gold, the panel is then burnished with a hard object, usually the tooth of a carnivorous animal, resulting in a lustrous dark gold.

The presence of gold makes the paintings themselves true gems, with a value that goegs beyond their merely artistic worth. Cellini recommended that gold used for gilding should be of the highest possible quality and purity, specifically 24-karat. Gold — not real this time but imitated by paint — is also present in the jewellery of both the Virgin Mary and the saints. All three are wearing a gold crown of intertwined acanthus leaves, decorated with rubies and what appear to be sapphires. Both stones were used by the highest echelons of social and religious hierarchies and the ruby was also associated with virtue and spirituality. In addition, St. Catherine’s crown is decorated with motifs comprised of four pearls.

St. Margaret is holding a gold cross decorated with four big sapphires at the ends of each arm and a ruby in the centre. The ring that the Baby Jesus is about to put on St. Cathereine’s finger to seal her mystic marriage is gold with a stone on it.

In 16th and 17th century Europe, tainted by religious wars, the political character of jewels — as we have noted — was joined by an important religious symbolism, in that they tied the wearer to one particular faith or another. The message that devotional jewels contained would have been essential to establish a complex network of relationships between the different powers.

Peter Paul Rubens

Portrait of a Young Woman with a Rosary

ROOM 19

In Portrait of a Young Woman with a Rosary (c. 1609-1610) by Peter Paul Rubens shows an unknown lady holding a rock crystal rosary in her hands. The richness of her attire has led her to be identified as some member of the court in Brussels. Yet it must be noted that the clothing worn by Antwerp’s prosperous merchant class was just as lavish as that of the aristocracy, so it is not so clear that she was tied to the court.

The portrait is dated between 1609 and 1610, by which time Rubens had already settled in Antwerp following his return from Italy in 1608. During this period he had already been appointed official court painter to the archdukes Albert and Isabella.

After eighty years of war between Spain and the Northern Provinces, the so-called Twelve Years’ Truce or Treaty of Antwerp was signed in 1609, the year that the portrait was executed. The archdukes implemented a policy of internal reorganization and reparation yet the Spanish Crown, which was Catholic and represented by the Archdukes, had not given up; a truce was simply in their best interest so they could concentrate their troops in other parts of Europe.

The fact that this woman is holding a rosary in her hands, an object related to a form of prayer promoted and encouraged by the Dominican Order, has been tied, as Gaskell has noted, to the sitter’s own faith. A rosary of roses was the object that the Virgin Mary gave to the founder of the Dominicans, St. Domingo de Guzmán, which aided the saint in his victory against the Albigensian heretics. The rosary is a type of devotional jewellery, with direct ties to religious symbolism. Yet we can also make another reading, going beyond the woman’s religion to tell us about her political and ideological stance. The presence of the rosary alludes to a Catholic sect that allows us to situate this woman in the area ruled by Spain rather than the Protestant territories. The public expression of faith had become, for Spain, a matter of State. Not just the monarchy but also the rest of the populace flaunted the precepts defended by the Church of Rome by wearing pieces of jewellery of higher or lower quality depending on which social class they belonged to. These pieces usually alluded to aspects of Catholicism challenged by Protestantism such as the Holy Trinity, images of saints, the Immaculate Conception or rosaries, whose religious symbolism we have already mentioned.

This woman is also wearing another type of jewellery of a more ornamental nature, or as accessories to her attire. We’re talking about two gold pins with pearls dangling from them that were used to hold her headpiece in place, the chain around her waist and her bracelets, all of them gold. The presence of the latter shows a transition to a new era through fashion. During the Renaissance sleeves were still quite long, covering up much of the wrist and hand; thus, rings were usually worn on the fingers but bracelets were uncommon. These pieces did not become popular until the 17th century. In this painting the sitter is wearing two identical bracelets made of solid gold, reflecting the fashion of wearing them in pairs.

As for the chain around her waist, it is a low V-shaped belt that marked the silhouette according to the fashion of the period. It is made up of fluted gold links. The bow that decorates this belt seems to be of fabric, although during the 17th century it was very fashionable to use precious stones and metals to imitate textiles. Different elements such as reliquaries, medallions and watches were often hung from these chains, as might be the case of this one here, although this would be only a guess as the end of the belt has been left out of the scene.

Peter Paul Rubens

Venus and Cupid

ROOM 19

Peter Paul Rubens also painted Venus and Cupid (1606-1611), a work in which the pearls worn by the goddess give the work a symbolic meaning of a mythological nature.

Having taken up painting at a very early age and with extensive Humanist training, Rubens combined his work as an artist with a brilliant diplomatic career that took him as a diplomat — and also as a painter — to Italy, Spain, France and England. In fact it was precisely on a diplomatic mission to Spain in 1628 that he became interested in the royal collections, particularly the paintings of Titian which, according to Pacheco, he copied in their entirety. A 1636 inventory of paintings in Madrid’s Alcázar palace includes a description of a work by Titian — which has been lost — depicting a Venus and Cupid that is almost identical to the Rubens composition, with very few differences between the two.

In the Thyssen painting we can see the Roman goddess of love and beauty accompanied by her son Cupid, the god of love, who appears as a winged boy. He obligingly holds up a mirror to a half-naked Venus who gazes at her reflection, admiring the full extent of her beauty. Characterized as Venus we can recognize Helena Fourment, Rubens’ second wife and the painter’s muse. Forment, who was 37 years younger than the artist, lent her face to the picture. The dynamic composition, rich palette and dynamic execution and forms are noteworthy characteristics also found in other works by Rubens.

Two elements give the work a symbolic meaning: the mirror and the pearls. The use of the mirror during the Renaissance and the Baroque period would give the painting a multiple frontality that signifies the reaffirmation of enjoying beauty itself: Venus can contemplate her full beauty. This broader vision in painting will lead it to compete with sculpture to be the greatest of all the arts.

A piece of jewellery, the pearl bracelet that adorns Venus’ right wrist, also gives the work a symbolic meaning of a mythological nature by allowing us to identify the main figure. There are many different versions about the birth of Venus. One of the most popular ones is that she was born of the foam that formed in the sea when Cronos cut off his father’s genitals and tossed them into the water. Venus emerges from the sea, just like pearls. Referred to in gemology as organic gemstones, pearls are of animal origin, just like coral and nacre.

Pearls had been highly prized since Antiquity. Their use as a personal adornment (in Greece ground up pearls were used to adorn the hair) indicated that the wearer had a lot of disposable income. During the Renaissance, several European countries even passed laws restricting the use of pearls to the nobility. In addition to being a status symbol, pearls were thought to bring happiness to the wearer and in the East, many people still believe that wearing pearls on one’s wedding day brings good luck.

Pearls are made up of nacre or mother-of-pearl, a substance comprised of calcium carbonate and other organic materials produced within mollusc shells. Although most bivalve molluscs can make pearls, the ones used in jewellery-making come from pearl oysters. Fine pearls, as they are known, are found loose inside the mollusc unlike other pearls, which are attached to the oyster’s shell. They are the product of a biological process, for this is the oyster’s way of protecting itself from harmful particles.

In the early 20th century, the Japanese entrepreneur Korichi Mikimoto came up with a method to produce cultured pearls at oyster farms. Man intervenes in the early stages of the pearl’s formation by inserting a little sphere of nacre into the oyster in a piece of mantle tissue extracted from another oyster.

A pearl’s value is determined by criteria such as its shape (perfectly round spheres or teardrop-shaped pearls are the most valuable), the rarity of its colour (they range from white to black), and its size.

The value that the upper classes attached to works of art made out of precious metals and stones was by no means exclusive to the West; they reflect the organization of any society. Not only does the Orient share these characteristics, it is also the place where many of these gems come from.

Johann Zoffany

Group Portrait of Sir Elijah and Lady Impey

Not on display

In Group Portrait with Sir Elijah and Lady Impey (c. 1783-1784) by Johan Zoffany we have a magnificent example of Indian jewellery.

Johan Zoffany went to India in search of new clients after realising that in England, the genre that had earned him a reputation — group portraits where people are talking to each other in a relaxed family atmosphere — had gone out of style. There he worked for high-ranking officers of the Crown and the large British community, which he painted either individually or as a group, applying the formulas that had made him popular back home.

Following the loss of the North American colonies, the British increased their presence in India during the 18th century and acquired strategic bases all along the trade routes between India and the Far East. In 1773 the British government was forced to take control of the East India Company, which was having financial problems and had been operating in India since 1600.

In the 18th century, India was under the rule of the Mongol Empire. During this period, power in the region reached its peak, extending from the Indian subcontinent to Afghanistan. It was a powerful Turkish-Ottoman state and its wealth in India was so great that it was one of the richest of its time.

The people of India had adorned themselves with jewels for centuries, but for the royalty — as in Europe — they were also a symbol of power and a divine connection, especially for the Maharajas and other members of the royal family.

Despite colonization, domestic and traditional life — and above all religious life — remained the same for the Indian people. During this period, weapons, lavish furniture and everyday articles were made for important figures and the wealthy individuals who could afford them, as well as for exportation. It was a time when the art of making pieces that combined the techniques and styles of Hindu and Islamic cultures was perfected and mastered. Themes stayed true to Hindu iconography, representing plants, animals, mythical figures from Indian folklore and scenes from everyday life, though certain geometric elements of Persian origin were also incorporated.

In this Zoffany painting we can see how the nannies are wearing traditional saris and a great deal of jewellery. In keeping with tradition, women and jewels are closely related. In wedding ceremonies, for example, parents and relatives always give jewels to the bride.

Although gold was the most widely-used metal, silver was also very common since it was easy to acquire, which made it popular among the lower classes. In the case of the nannies in the Zoffany painting, silver seems to be the predominant material although there are also some darker pieces that might be made of copper, another material that was used for adornments along with precious stones and ivory as well as seeds, flowers, bones, teeth, feathers, etc. For instance, the musician playing the triangle is wearing a necklace that seems to be made of wood or seeds, and the nanny who is swatting at flies is wearing a red ribbon tied with a bow along with a bracelet or bajuband.

Traditional Indian jewellery is as diverse as the country itself, and there are pieces that adorn practically every part of the body. Each region has different types of jewellery and each state has a style of its own that makes it original and unique.

Depending on where they are worn, we can also talk about facial jewellery and body jewellery. The nannies in the Zoffany painting are wearing both types. As for facial jewellery we can see a nose ring called a nathni o nath, koka or laung. It originated in the Middle East and was introduced into India with the Mongol invasion. Jhumka, or earrings, were one of the most common accessories and could be worn by both men and women.

There are many different types of body jewellery. The haar, or choker, and the bajuband, or arm bracelet, are usually made out of raw metal with intertwined plant and animal figures such as serpents or crocodiles. The nanny on the right is wearing one that seems to have stones dangling from it. Chudi or kangan are types of bracelets. In India they are generally worn in pairs — more than one pair on each arm — and are usually made of gold or silver. In this case they are identical. T

he bracelets also have an important meaning in the Hindu religion, as it is regarded as “unfavourable” for a woman to leave her arms bare. The musician with the triangle is also wearing a chudi but it is much less ornate. Angoothi are traditional rings and both women are wearing them on almost all their fingers. Payal or pajeb are ankle bracelets, one of the most traditional pieces of Hindu jewellery. They were worn by women of all ages and were popular due to their exquisite, flattering designs. This is the case of the only one we can see on the nanny on the left; the bracelet around her ankle seems to have pieces dangling from it that would surely jingle when she walked. They were worn for any occasion, even on an everyday basis. The women also have bichua or toe rings. In the past these pieces were worn by married women, so we can assume that one of the nannies, the only one whose foot is shown in the painting, had a husband. The word bichua means scorpion and these rings are not closed like the ones worn on the hands, but open at one end so they can be adjusted to the toe by squeezing them shut, just like the tail of this animal.

Over the course of the 17th century, and definitively in the 18th century, modern jewellery emerged thanks to a combination of profound changes in the evolution of this art form. This brought the loss of some of its meanings, fundamentally those tied to magic and healing, in favour of its decorative function. From then on, its technical or artistic qualities would become more important and the beauty of the actual stones would be valued more than their material worth. The first reason for this is that the art of cutting gems was perfected, making them look more beautiful and brilliant than ever before, and they began to be mounted in a lighter way so that the setting becomes invisible, focussing all the attention on the stone.

But the truly transcendental change was the increasingly clear separation between the fine arts and the decorative arts. Painters, goldsmiths, sculptors, etc. ceased to belong to the same category. Each discipline became specialized, and just as still life painters were inferior to painters of historical subjects, the goldsmith was not always an enameller or a carver. This period brings the birth of the jeweller, the person who designs the pieces and does the most delicate work whereas the role of the goldsmith became less important.

John Singer Sargent

Portrait of Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland

ROOM 32

This return to a more classic, elegant style can be seen in the superb Portrait of Millicent, Duchess of Sutherland, dated in 1904. It is one of the last works by John Singer Sargent (three years after it was painted he would close his London studio), who was acclaimed as the finest portraitist of the fin-de-siècle and one of the most highly soughtafter painters of the English aristocracy. Born in Florence in 1856 to American parents, he reconciled his cosmopolitan nature (after studying in Italy, he spent the rest of his life between Paris and London, with stays in the United States and summers in picturesque parts of southern Europe and the Alps), with a rigid society that demanded classic portraits, defending 18th-century paintings as models of elegance to be followed.

In this portrait, which recalls the work of the great masters who Sargent admired, we can see how the landscape — a subject that he had been practicing since his childhood in Florence encouraged by his mother, an amateur painter — is masterfully combined with the predominance of colour over drawing and the depth of the psychological portrait, features that would be a constant in Sargent’s paintings after he discovered the work of Tintoretto on a trip to Venice as a young man.

In this case the sitter is Lady Millicent, one of the most influential, progressive women of Victorian England. Born in Scotland in 1867, she was known not only for her serene beauty, which Sargent captures in this large portrait, but also for her work as a writer, even as a champion of women’s’ rights. At the age of 17 she married the future Duke of Sutherland, a high-ranking military officer, with whom she had four children. The couple divided their time between their London residence across from Buckingham Palace and their castle in the Highlands of Scotland where, according to the tastes of the period, they designed a great garden inspired by Versailles. This garden may have served as the setting for this painting.

Millicent, shown in full length (a pose traditionally attributed to nobility in portraiture, with the goal of showing all the attributes of its greatness), seems to emerge from the shadows of the garden. With one hand resting on a fountain that makes her figure twist, showing off her curves, she is wearing an elegant gown with a low neckline that reveals her shoulders and white aristocratic skin. She is crowned by a gold tiara in the shape of a wreath of laurel leaves or perhaps myrtle, in the Neoclassical style characteristic of the 19th century. The sitter has a majestic quality that brings to mind the great portraits of French aristocratic ladies who were depicted as crowned, hunting Dianas. Millicent emerges from nature like a Belle Époque goddess.

The word tiara — which is semi-circular in shape, as opposed to the diadem which is closed — derives from the ancient Persian tiyara, which referred to the headdress that monarchs wore as a sign of authority. The Greeks used laurel or olive wreaths to crown the winners of public games, the Roman emperors being the first to replace real leaves with leaves of gold. After becoming an exclusive symbol of royalty, the tiara evolved over the centuries into precious metal pieces worn as a sign of high status.

Even though in 1804, Napoleon II’s lavish coronation brought back into vogue the crown in the shape of a laurel wreath, like the ones worn by Roman emperors, great tiaras did not appear until the beginning of the 20th century. They came to occupy a predominant place in the field of jewellery, perhaps as a nostalgic dream that had its last heyday during the Belle Époque.

The 1920s, however, brought a revolution in the world of fashion, when the rigid style of the 19th century was rejected in favour of freer, more sophisticated silhouettes. Garments with straight lines provided a freedom of movement very much in keeping with the modern woman, a woman who is no longer a recluse at home but who goes out at night, travels, plays sports, drives and even smokes. These simple, elegant, slender silhouettes were enhanced by beautiful pieces of jewellery, which became the ideal accessories. Brooches, pins and pendants offer a repertoire of forms very much in keeping with the spirit of the times: a bourgeois, purely decorative, elegant, functional, modernist style that emerges as a reaction to austerity after World War I and as a step forward with respect to Art Nouveau. It would be Art Deco pieces that would constitute, in and of themselves, modern beauty.

This style took off in the context of the 1925 International Exhibition of the Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts in Paris, where a group of designers dedicated to avantgarde decorative arts presented the latest trends in both the decorative arts (furniture, interior and jewellery design) and the visual arts (painting and sculpture). The goal was not so much to promote a new art form but to show works that were to the taste of rich clients, the true ambassadors of Art Deco.

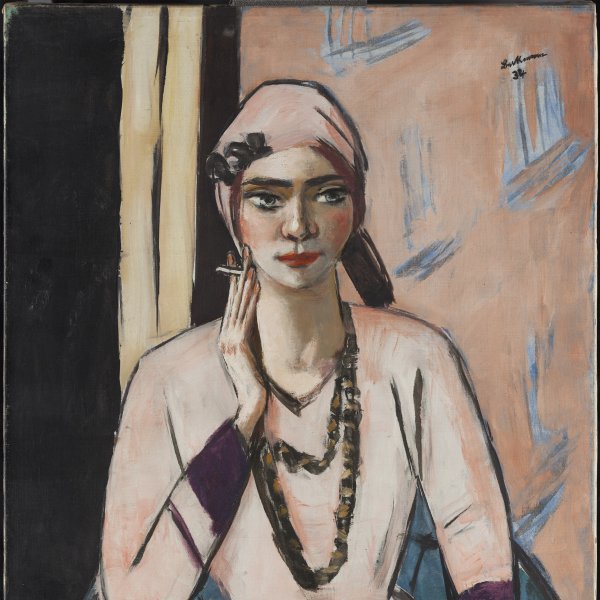

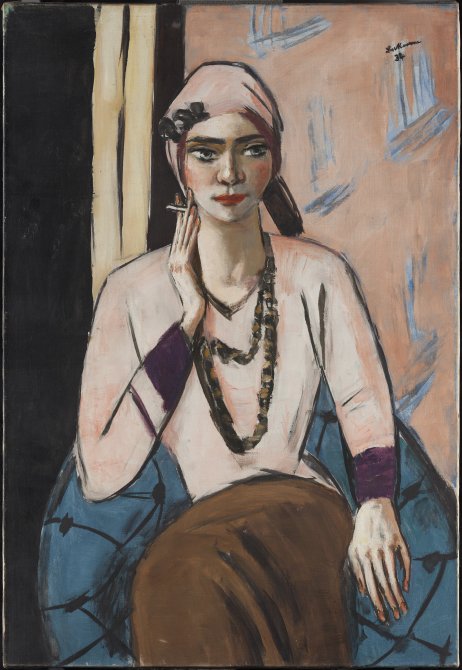

Max Beckmann

Quappi in Pink Jumper

ROOM 45

1925 was an also an important year for the German painter Max Beckmann. After divorcing his first wife he married Mathilde “Quappi” von Kaulbach, a woman 20 years his junior. The daughter of the German painter Friedrich August von Kaulbach, Quappi was a very educated woman. Though she had trained to be a great violinist like her mother, she gave up her career and studies to marry Beckmann, throwing herself into the role of artist’s wife.

Beckmann would paint his wife on numerous occasions as an example of the new modern woman. In Quappi in a Pink Jumper (1932-1934) she is looking straight out at us, sitting in a blue chair with her legs crossed. The young woman is captured in an elegant pose and has the air of a modern woman, due to her attire, the way she is sitting in the chair and the fact she is holding a cigarette. According to Quappi herself, most of her portraits intended to stress one particular item of clothing, in this case a striking pink V-necked jumper with a matching pink turban. As accessories to her outfit she is wearing a two-stranded necklace and a brooch that gives her a 1930s sophistication.

Art Deco jewellery designs went from smooth, flat finishes to very large, colourful pieces. Paradoxically, the crash of ’29 brought an explosion of creativity that manifested itself in pieces of unprecedented opulence. This is when, due to the high price of precious stones, jewellery makers began to use semi-precious stones and pate de verre in their pieces.

The portrait was executed in two phases: first in 1932, when according to various sources a Quappi had a more open smile; and then in 1934, when Beckmann decided to give his wife a more serious expression, perhaps due to the couple’s concern about the rise of National Socialism. From an artistic standpoint, the flat forms, the interplay of colours and the thick black sketch-like brushstrokes inevitably bring to mind the work of Matisse.

The incursion of the so-called avant-garde artists into the world of the applied arts in general and jewellery in particular was a quite common occurrence, allowing them to show their artistic ideas in the form of these small objects.

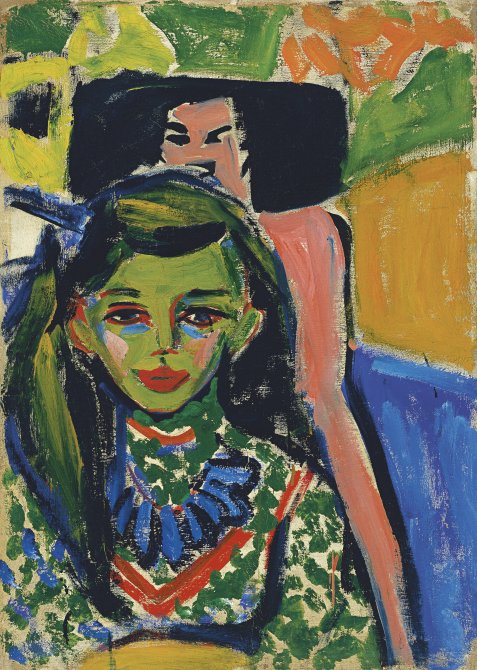

The integration of all the arts — promoted since the mid-19th century by movements such as Art & Crafts, eliminating the boundaries between different fields — favoured this trend. In some way, the goal was to restore an artistic dimension to everyday objects, something that had been lost with industrialization. One of the groups that produced pictorial works as well as everyday objects, particularly jewellery made out of metal, was Die Brücke (The Bridge), a German group founded in Dresden in 1905 by Fritz Bleyl, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt- Rottluff, all of them students of architecture and self-taught artists.

In its 1906 manifesto, they presented themselves as a group of artists against contemporary art and culture and in favour of creative freedom who rejected all inherited forms. They saw art as a reality seen through the temperament, making the work of art a vehicle for conveying emotions. This is evident in their use of colour, applied in an arbitrary manner on large surfaces with sharp contrasts.

This group took an interest in primitive cultures, which they discovered at the Dresden Ethnology Museum (inaugurated in 1910), not only for aesthetic reasons but also because they shared the idea that art is a means of expression that allows sensations to be conveyed in a free, direct manner.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

Fränzi in front of Carved Chair

ROOM 35

One example of this can be found in Fränzi in Front of a Carved Chair (1910), by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. It is a half-length portrait in which we can see the young Fränzi with her face painted green. She is well-dressed and is wearing a large, very striking necklace of blue pieces, reflecting this taste for the primitive. The portrait offers us a subjective representation of the model, far from the traditional examples of the genre. The young woman is leaning against the back of a roughly carved chair (surely made by Kirchner himself) that adopts a female silhouette. Unlike Fränzi, she appears nude and has been intentionally painted in very natural flesh tones. The portrait explores the idea of sensuality and primitivism and the young, innocent woman versus the femme fatale.

That was precisely the year that Karl Schmidt-Rottluff started to make jewellery out of silver, a softer material than the brass that he may have worked with before. Apparently this interest in silver jewellery infected the rest of the group’s members, who used semiprecious, untreated stones such as raw, irregular-shaped minerals, which became the true centrepieces of designs with a marked primitive look. It was a multifaceted endeavour where they not only designed the pieces, but they also produced them in an artisanal way. They were more interested in the technical aspects of jewellery-making than by the aesthetic forms. This manual labour allowed them to get closer to primitive expression and reflect about original artistic forms. With this work, they aimed to apply their art to life through the objects that were part of it. These pieces became a mirror of their attitude toward life.