By José Ramón Fernández

When we say the performing arts, we mean everything that is put on before an audience with an artistic intention, including theatre, dance, music, circus and more. This artistic intention encompasses not only eminent figures but also, of course, street artists. Someone displays themselves before others with the intention of conveying or sparking an emotion. The performing arts are an arena of encounter.

On the one hand, the relationship between the play and the audience takes place in the presence of some of the artists responsible for it and may be significantly changed by the viewers. A novel, a poem, a painting or sculpture are works of art which are not changed by the people enjoying them. A theatre, opera or dance performance, as well as any public performance of musical pieces, is often transformed by what today we call their “reception”.

On the other hand, and this is what we aim to show in this journey, the performing arts are a complex arena for the convergence of different arts, where they can infect one another. A live show may bring together such disparate disciplines as music, dance, literature and the visual arts.

In a theatrical, choreographic or circus piece, we find pictorial elements in the set, the costumes, the lighting, and the very gestures of the performers. In fact, this is true to such an extent that the sets or costumes for shows have often been designed by painters.

If we think about this vast trove of signs related to painting, it is inevitable that among the works that populate a collection as rich and replete with nuances as the holdings of the Museo Thyssen, we find testimonies of this encounter between the performing arts and painting.

Of course, there are more possibilities for this journey, but as lovers of printing, more than once we have all experienced that exhaustion that hinders us from enjoying the works because we have been standing for too long, or simply because our eyes need time to digest what they are seeing. Therefore, it is wise to exercise caution in order to ensure that a surfeit of information does not turn into noise. For this reason, we have chosen a limited number of paintings. Nonetheless, we would like to take advantage of this introduction to suggest that you visit the mediaeval, Renaissance and Baroque painting galleries and look, for example, at three realities from our cultural heritage: the Greek tradition, paintings related to Nativity plays, and the paintings of musicians.

First of all, it is worth recalling that Greco-Latin culture is one of the foundations upon which our worldview is grounded. Ancient Greek theatre and the three great Greek tragic playwrights, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, were a prominent part of this foundation. Of all the great works in this early chapter in our culture, Medea particularly stands out, the sorceress princess who avenges Jason’s betrayal of her by killing her own children. This story has particular resonance in our country because of the mythical version by Miguel de Unamuno with which Margarita Xirgu and Enrique Borrás officially opened the Teatro Romano of Mérida in 1933, launching one of the most famous cultural events in our country: the Mérida Classical Theatre Festival. The story of Medea – who betrays her homeland and family to help Jason and his Argonauts steal the Golden Fleece, and who is later abandoned by Jason and takes revenge on him by killing their own children – is part of the Western literary and cultural tradition. The Thyssen Museum offers two views of this story: the painting by Enrico de Roberti, The Argonauts Leaving Colchis, and the work by Jean-François de Troy, Jason and Medea in the Temple of Jupiter.

After an almost one-thousand-year hiatus, in the Middle Ages theatre was revived in churches, accompanying the major celebrations. The first dramatic texts in Spanish are Nativity plays, and they recount the birth of Jesus, the annunciation to the shepherds and the adoration of the Kings. The oldest Spanish text is a play about the Three Wise Men. This prominence of religious subjects can be seen in works like Adoration of the Magi by Luca di Tommè and The Nativity by Barthel Bruyn the Elder.

At the same time, there has always been some form of street art: storytellers, jugglers, musicians... festivities and streets. Our Pierrot Content by Watteau could also inspire a visit to paintings that depict friends congregating at festivals, gatherings in the countryside, street musicians, people of any origin who find happiness in music. While I will omit them from our journey, I must cite this clutch of works: Uncle Paquete by Francisco de Goya, Portrait of Count Fulvio Grati by Giuseppe Maria Crespi, Fisherman Playing the Violin attributed to Frans Hals, The Happy Violinist by Gerrit van Honthorst, The Young Musicians by Antoine Le Nain, Group of Musicians by Jacob van Loo, Oyster Eaters by Jacob Lucasz Ochtervelt, Concert Champêtre by Jean-Baptiste Pater, The Village Fête by David Teniers and Self-Portrait Playing the Lute by Jan Havicksz Steen. Even Shahn, Braque and Miró joined this celebration of joyful musicians.

Obviously, one special painting located on the second floor of the museum deserves special mention: Hans Wertinger’s portrait of a comic, The Court Jester Known as ‘Knight Christoph’. The portrait of one of the Duke of Bavaria’s jesters reveals to us the importance of his status in the court at that time. The date of the painting precisely points to this revival in theatre, which had languished during the first few centuries of our era and came back to life at the end of the Middle Ages. Over the course of those centuries, clowns, buffoons, and travelling comics were the ones who kept alive this artistic discipline which seemed to have died forever.

In short, we have chosen twenty paintings from this wonderful collection to suggest a journey through the performing arts which sparks curiosity and goads you to learn more about theatre, music, dance and circus so that you can revisit these amazing painters who have surely brought you a few moments of happiness.

One last note: we are presenting the paintings in chronological order. Of course, there are infinite ways to take this journey, and this is only the most obvious one. Enjoy your trip!

Tour artworks

Jean Antoine Watteau

Pierrot Content

Not on display

It is 1712, the twilight years of the reign of Louis XIV, the Sun King. The French nobility, joyful and heedless, spiced up their nights with what were known as fêtes galantes. Games, costumes, music… If you want to imagine those pleasant moments, we recommend a stroll through gardens in Madrid built several years later in the fashion of that era, the gardens of the El Capricho estate, which used to belong to the Dukes of Osuna and are today open to the public. The Anglo-Chinese garden was a game in itself: seemingly wild wooded nooks, a smattering of pods, a labyrinth, a haunted house, automatons… Right around that time, in the era when the French nobility entertained themselves with these soirées, is when Jean-Antoine Watteau began to paint.

What this small painting shows is one of those nights, a fête galante. A woman is playing the guitar, and two of the men are dressed as figures from the Commedia dell’arte, Mezzettino and Pierrot.

Watteau had been trained with the set designer Claude Guillot, and there in the theatre he found one of the motifs that we most closely associate with his paintings: the characters from the Commedia dell’arte, or more specifically Comédie Italienne or Italian comedy, the way in which that form of popular theatre had evolved in Paris.

The Commedia dell’arte had existed since the 16th century and was merely an evolution of the comedians in 1st-century Rome, when Plautus and Terence forged many of the characters who have populated thousands of comedies, even down to today. The mischievous servant who could not withstand the temptation of pulling pranks without thinking of the consequences, that is, Harlequin, Mezzettino, and Scapino, are the distant kin of Bart Simpson, just as the old Pantalone is the forerunner of Molière’s Misanthrope or Mr Burns. The Commedia dell’arte revived those characters, and the village squares filled with comedians who improvised their plays based on a brief canovaccio1 or scheme. A pair of lovers, a jealous old man, muddles and treachery, acrobatics, surprises, hilarious servants that throw everything into disarray… Pure entertainment.

This popular theatre spread all over Europe. Cervantes mentions his memory of the first comedians and of Lope de Rueda, who introduced it into our country. In France, the troupes that performed Commedia dell’arte called it Comédie Italienne and were extraordinarily popular throughout the 17th century. Their forms eventually became more refined, and they stopped using masks. They were the popular theatre, not the official kind, and they were met with resounding success. The stiff competition they posed to the official troupes led them to be banned. It is fascinating that by the time Watteau painted this painting, his characters could no longer be seen onstage. Shortly thereafter, the ban was lifted, they were allowed to put on plays by French authors and they became the favourites of the great playwright Pierre de Marivaux. While Marivaux joined the fate of his comedies to these characters, we can also find their echoes in Molière, in the “jesters” of Spanish comedies, and later in the characters in the comedies by Beaumarchais, The Barber of Seville and The Marriage of Figaro.

So the characters in the Comédie Italienne were fashionable in Paris, and Watteau brought them to painting. Not only did he paint them; he painted them to turn them into a motif, a myth. Scaramouche, Harlequin, Mezzettino, Pantalone, Aurelia, Diamantina... So what about Pierrot?

Pierrot is an evolution of the character Pedrolino, the honest and somewhat naive servant who is thus the antithesis of Harlequin. They have gone hand in hand for centuries, the good one with the white face and the mischievous one in the colourful outfit and black mask; the whiteface clown and the jester. Watteau turned kind-hearted and melancholy Pierrot into an icon for art. We shall not dwell any further on this explanation because we are going to meet up with our friend again later in this journey. Pierrot became popular in Paris thanks to an actor, Giuseppe Giratoni, in around 1665. So when Watteau made this painting, he was spotlighting a character who was very popular in his country. Watteau made Pierrot the main character in other paintings, too, especially in the one on display today in the Musée du Louvre in Paris.

Our image of Pierrot is somewhat different to the one Watteau depicts. Another actor, Jean-Gaspard Deburau, gave him his definitive personality as a melancholy whiteface clown in the early 19th century. Based on the image created by Deburau, the endearing Pierrot definitively became an icon of painting. We cannot avoid the memory left in the cinema by the brilliant French actor Jean-Louis Barrault in the Marcel Carné film Children of Paradise (1945).

1The scripts that were used for the Commedia dell’arte were called canovaccio (schemes). They were notes based on which the actors improvised the action.

Johann Zoffany

Portrait of Ann Brown in the Role of Miranda (?)

ROOM 24

Now we are looking at a different painting, at least among Spanish fans. It is the portrait of an actress dressed in character with the set of a play as the backdrop. This kind of painting is somewhat unique here, but it used to be fashionable in England, and one particularly prominent practitioner of that fad was Johan Zoffany, an artist from Germany who worked in England, where he developed his career and achieved success with his theatre scenes. In fact, his friendship with the most celebrated actor of the day, David Garrick, is what set him along this pathway. In 1760, Zoffany began to work in a studio as a drapery painter; that is, he painted folds of clothing. That was where he met Garrick, some of whose best portraits we owe to Zoffany, even one of the more curious ones in which the actor is dressed as a woman in a comedy.

Garrick saw the usefulness of those portraits, since engravings of them were distributed as advertisements. In this way, the paintings were both a way to be on par with the personalities from English high society and a form of advertising among the lower classes. We are talking about the stars of the day, such as Garrick and the Irish actor Charles Macklin in the role of Shylock the Jew in William Shakespeare’s 1741 play The Merchant of Venice.

The woman in the painting is apparently Ann Brown, who had been a member of Garrick’s troupe. Brown appears here in costume for the role of Miranda in The Tempest or The Enchanted Island, the Henry Purcell opera based on William Shakespeare’s The Tempest. In the background, we can see what must have been the set of this opera. The young woman drawing a heart on the stone is Miranda, the daughter of the magician Prospero, who has fallen in love with a shipwrecked young man, Fernando.

To be more precise, The Tempest or The Enchanted Island is a comedy written by John Dryden and William D’Avenant. It is a rewriting of Shakespeare’s play, which was quite common back then, when there was no protection of intellectual property. Thomas Shadwell adapted that text to turn it into the libretto of the opera which has been attributed to Purcell, although some scholars believe that its real author was John Weldon. The opera premiered in 1695.

Ann Brown had acted in David Garrick’s troupe between 1769 and 1770, and later she continued her career in Covent Garden from 1772 to 1776. After marrying, she embarked upon a tour of India as Mrs Cargill and drowned to death in 1784; the boat that was conveying her back to Great Britain sank. She was highly celebrated in her lifetime because of her considerable skill as an actress, and because stories of her lovers further magnified her legend, so London mourned her premature death in the late 18th century.

We cannot leave this visit to Prospero’s island without recommending another journey. In Bath, the English city known precisely for its Roman baths and streets which have served as the set of many films based on the novels of Jane Austen, there is a collection of paintings on theatre assembled by Somerset Maugham. This novelist and playwright, who was extremely popular during his lifetime – even today; some of his novels are still being brought to the cinema, including Being Julia featuring Annette Bening and Jeremy Irons and The Painted Veil starring Edward Norton and Naomi Watts – spent part of his vast fortune buying paintings related to the English theatre in the 18th century. He donated his collection to the National Theatre, which lent it to the outstanding Holburne Museum of Bath just four years ago when it reopened its doors after a carefully planned refurbishment. Thus, on the second storey of this fascinating museum you can see several of Zoffany’s paintings depicting theatre performances in 18th-century England, including one that has been reproduced often: the legendary Garrick dressed as a woman for the John Vanbrugh comedy Provoked Wife.

Edgar Degas

Swaying Dancer (Dancer in Green)

ROOM 33

The world of dancers was particularly appealing to Impressionist painters because of its beauty, the difficulty recreating movement and the phenomenon that came with it: artificial light. Indeed, dance is the arena where Degas was best able to capture the sense of movement in painting.

Degas adopted the vantage point of someone in a box overlooking the proscenium, that is, those sitting the closest to the stage. By doing so, he turned us viewers into spectators at this ballet. In his painting, two points draw our eyes: first, the strange light that the footlights are casting on the dancers onstage. The footlights are the name given in theatre to the row of lightbulbs (in the past, gas lamps, and even before that, candles) which illuminate the stage from the floor, right at the edge. This almost ghostly light was somewhat exclusive to stages until the mid-20th century. On the other hand, the painter also shows us the dancers waiting in the wings for their turn to go onstage, contrasting the graceful movements of the dancers with the relaxed stances of those backstage. This painting does not depict angelic beings who deliver their art effortlessly but artists whose posture hints at their exhaustion, that is, toil. We have used the theatre expression “in the wings”, which is the space offstage to the right or left of the acting area hiding the lighting and the performers and technicians. Sometimes you may hear “backstage” instead, but this actually refers to any area “behind the scenes” or out of the public’s view, not just the wings.

A stage is always a magical place which sparks our curiosity, just as it did with Degas in this painting. We want to glimpse this area behind the curtain, where the magic is concealed. And this is precisely what Forain does: he shows us that magical world backstage, where the dancers are sitting in relaxed postures or tying their ballet slippers. Forain shows us the beauty of these beings when the audience is not watching them, their grace in any posture, the play of light on their romantic tutus, which seem to dissolve into the air. Forain liked to paint dancers when the show was over in the company of the gentlemen who attended the theatre as if it were a meat market. There are accounts of a celebrated scandal that took place at the premiere of Wagner’s Tannhäuser. In Paris, it was customary for the operas to have a ballet, and this ballet did not start until ten in the evening. The gentlemen had dinner at the Jockey Club and afterwards entered the theatre like its proprietors and lords, when the show had been running for some time already, just to watch the ballet. Wagner moved the ballet to the beginning of the evening, immediately after the overture, and it was an utter failure in Paris in 1861: the gentlemen had missed their dancers.

That gallant, modern world of the Opéra Garnier, the broad avenues… we are in the gleaming new Paris of 1874. The architect Haussmann had opened up the broad avenues we know today in the City of Light, and performances reached extraordinary levels of beauty and perfection. The Impressionists had developed the perfect technique to capture that ethereal beauty of the ballets, the tulle of the tutus, the movement, the colours… Today it is familiar to all of us: it is called “pastel” and Degas was one of its indisputable masters. But Degas and Forain were not only commenting on beauty.

Jean-Louis Forain

Dancers in pink

ROOM F

The world of dancers was particularly appealing to Impressionist painters because of its beauty, the difficulty recreating movement and the phenomenon that came with it: artificial light. Indeed, dance is the arena where Degas was best able to capture the sense of movement in painting.

Degas adopted the vantage point of someone in a box overlooking the proscenium, that is, those sitting the closest to the stage. By doing so, he turned us viewers into spectators at this ballet. In his painting, two points draw our eyes: first, the strange light that the footlights are casting on the dancers onstage. The footlights are the name given in theatre to the row of lightbulbs (in the past, gas lamps, and even before that, candles) which illuminate the stage from the floor, right at the edge. This almost ghostly light was somewhat exclusive to stages until the mid-20th century. On the other hand, the painter also shows us the dancers waiting in the wings for their turn to go onstage, contrasting the graceful movements of the dancers with the relaxed stances of those backstage. This painting does not depict angelic beings who deliver their art effortlessly but artists whose posture hints at their exhaustion, that is, toil. We have used the theatre expression “in the wings”, which is the space offstage to the right or left of the acting area hiding the lighting and the performers and technicians. Sometimes you may hear “backstage” instead, but this actually refers to any area “behind the scenes” or out of the public’s view, not just the wings.

A stage is always a magical place which sparks our curiosity, just as it did with Degas in this painting. We want to glimpse this area behind the curtain, where the magic is concealed. And this is precisely what Forain does: he shows us that magical world backstage, where the dancers are sitting in relaxed postures or tying their ballet slippers. Forain shows us the beauty of these beings when the audience is not watching them, their grace in any posture, the play of light on their romantic tutus, which seem to dissolve into the air. Forain liked to paint dancers when the show was over in the company of the gentlemen who attended the theatre as if it were a meat market. There are accounts of a celebrated scandal that took place at the premiere of Wagner’s Tannhäuser. In Paris, it was customary for the operas to have a ballet, and this ballet did not start until ten in the evening. The gentlemen had dinner at the Jockey Club and afterwards entered the theatre like its proprietors and lords, when the show had been running for some time already, just to watch the ballet. Wagner moved the ballet to the beginning of the evening, immediately after the overture, and it was an utter failure in Paris in 1861: the gentlemen had missed their dancers.

That gallant, modern world of the Opéra Garnier, the broad avenues… we are in the gleaming new Paris of 1874. The architect Haussmann had opened up the broad avenues we know today in the City of Light, and performances reached extraordinary levels of beauty and perfection. The Impressionists had developed the perfect technique to capture that ethereal beauty of the ballets, the tulle of the tutus, the movement, the colours… Today it is familiar to all of us: it is called “pastel” and Degas was one of its indisputable masters. But Degas and Forain were not only commenting on beauty.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Yvette Guilbert

ROOM 33

The drawings of henri de Toulouse-Lautrec are some of the most popular artistic expressions from the 19th century. That nocturnal Paris, the city of fun, earthier and more raucous than the dancers of Degas and Forain and furiously alive, bears his unmistakable imprint for many of us. Beyond the extraordinary quality of his works, his life circumstances turned him into a personality of his day: he was the son of a wealthy family but had a disease that prevented him from growing; he was the habitué of Parisian nights, the sketcher of the magical beings of Montmartre, the illustrator of the Moulin Rouge. Film lovers identify him with the face of José Ferrer in John Huston’s 1952 film, Moulin Rouge.

At slightly over the age of twenty, his drawings were published as illustrations for books and magazines and as posters to advertise the venues in the Montmartre neighbourhood, such as Le Mirliton cabaret and the celebrated Moulin Rouge. He became as famous for his drawings as for his scandals, and he left us a portrait of a city that never sleeps, full of dancing and music.

In this painting, Toulouse-Lautrec shows us a famous singer at the time, Yvette Guilbert; he depicts her at the moment in theatre circles known as the “curtain call”, when the performance is over and the curtain raised – or the lighting on the artist is turned up – so they can receive the audience’s accolades. Her demeanour is upright and dignified, lit by that blue blotch of artificial light from the footlights just a second before she begins to bow to the respectable audience. It is the greatest moment for stage artists. Guilbert was the star of the Divan Japonais, the Ambassadeurs and the Moulin Rouge cabarets. In this portrait, which was published in Le Figaro Illustré in 1893, Guilbert appeared with a very studied look; in fact, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen drew her in the same costume and hairdo as in the poster for the Ambassadeurs. She was the great singer and actress who embarked on international tours and worked in the cinema as well. Over the years, she also became an expert in ancient music, wrote several novels and was decorated with the Legion of Honour.

James Ensor

Theatre of Masks

ROOM 36

Two centuries after that Pierrot content which started our tour, we once again find a theatrical representation featuring Pierrot and Harlequin by a fervent admirer of Watteau, the Belgian painter James Ensor. Even though the painting is entitled Theatre of Masks, we can see that, following the tradition in Paris, Harlequin is barely wearing his black mask anymore. The others have painted faces. However, where we do find masks is among the audience at their feet, many of them in fancy dress. The low height of the stage hints at a popular street performance, and the audience’s clothing inevitably leads us to imagine Carnival, a special festival for the city of Ostend and for Ensor’s family, who sold Carnival masks in their shop. At that time, Ostend was a village in northern Belgium, very close to the English coast, which was highly prized for its beach and as an entertainment and holiday destination. Even though Ensor was a forerunner of the avant-garde painting movements, he hardly left his city. But the world went to Ostend on holiday. Ensor found the Carnival festivities, with their masks and colours, a place to develop his world, which falls somewhat between the grotesque and the disturbing. Many of his paintings depict Carnival, and the characters from the Commedia dell’arte often appear as well. In the Museo Thyssen, you can also find a painting made almost 20 years later that revisits these same characters, his Jardin d’amour.

In Theatre of Masks, James Ensor shows us the popular side of life, while by training his eyes on these simple characters, he began to set a trend that would become essential in the avant-garde arts: the presence of those characters descended from the Commedia dell’arte in music, theatre, poetry, dance and opera. In the early 20th century, their image would become inseparable from avant-garde art.

What we are looking at is a painting from his mature stage which he made almost at the age of 50, when he had already become one of the most prestigious painters in his country and begun to abandon some of the subjects that had made him a forerunner of Expressionism. Two years earlier, in 1906, he had begun to compose the music for a ballet, The Game of Love, for which he also designed the sets and costumes. He was involved in this project, which he completed in 1911, while he painted this Theatre of Masks.

Sometimes we may wonder what sounds and music accompanied an artist when he or she was creating a painting. In the case of James Ensor, who was also a composer, as we look at his painting we can imagine the sound of the melodies that he himself composed, such as his Vals Caprice.

Painter, musician, set designer, costume designer… it should come as no surprise that he also took decisions on the structure that holds this painting. If you look at the frame carefully, you can see that it is also quite special. Surely you have already spotted it.

James Ensor

Jardin d'amour

Not on display

Two centuries after that Pierrot content which started our tour, we once again find a theatrical representation featuring Pierrot and Harlequin by a fervent admirer of Watteau, the Belgian painter James Ensor. Even though the painting is entitled Theatre of Masks, we can see that, following the tradition in Paris, Harlequin is barely wearing his black mask anymore. The others have painted faces. However, where we do find masks is among the audience at their feet, many of them in fancy dress. The low height of the stage hints at a popular street performance, and the audience’s clothing inevitably leads us to imagine Carnival, a special festival for the city of Ostend and for Ensor’s family, who sold Carnival masks in their shop. At that time, Ostend was a village in northern Belgium, very close to the English coast, which was highly prized for its beach and as an entertainment and holiday destination. Even though Ensor was a forerunner of the avant-garde painting movements, he hardly left his city. But the world went to Ostend on holiday. Ensor found the Carnival festivities, with their masks and colours, a place to develop his world, which falls somewhat between the grotesque and the disturbing. Many of his paintings depict Carnival, and the characters from the Commedia dell’arte often appear as well. In the Museo Thyssen, you can also find a painting made almost 20 years later that revisits these same characters, his Jardin d’amour.

In Theatre of Masks, James Ensor shows us the popular side of life, while by training his eyes on these simple characters, he began to set a trend that would become essential in the avant-garde arts: the presence of those characters descended from the Commedia dell’arte in music, theatre, poetry, dance and opera. In the early 20th century, their image would become inseparable from avant-garde art.

What we are looking at is a painting from his mature stage which he made almost at the age of 50, when he had already become one of the most prestigious painters in his country and begun to abandon some of the subjects that had made him a forerunner of Expressionism. Two years earlier, in 1906, he had begun to compose the music for a ballet, The Game of Love, for which he also designed the sets and costumes. He was involved in this project, which he completed in 1911, while he painted this Theatre of Masks.

Sometimes we may wonder what sounds and music accompanied an artist when he or she was creating a painting. In the case of James Ensor, who was also a composer, as we look at his painting we can imagine the sound of the melodies that he himself composed, such as his Vals Caprice.

Painter, musician, set designer, costume designer… it should come as no surprise that he also took decisions on the structure that holds this painting. If you look at the frame carefully, you can see that it is also quite special. Surely you have already spotted it.

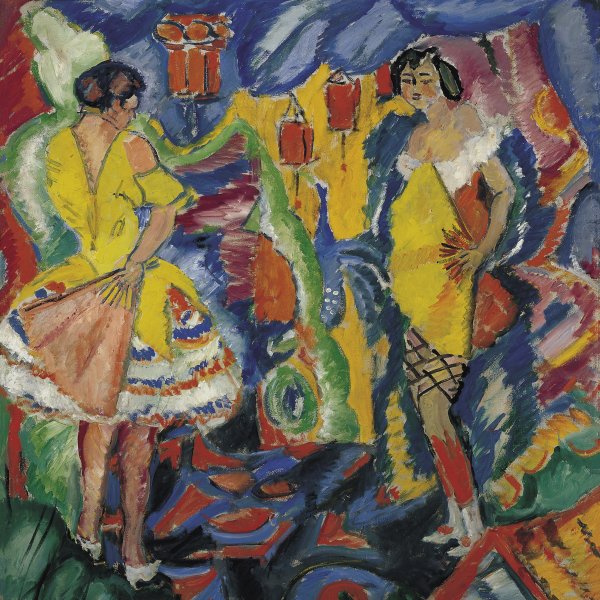

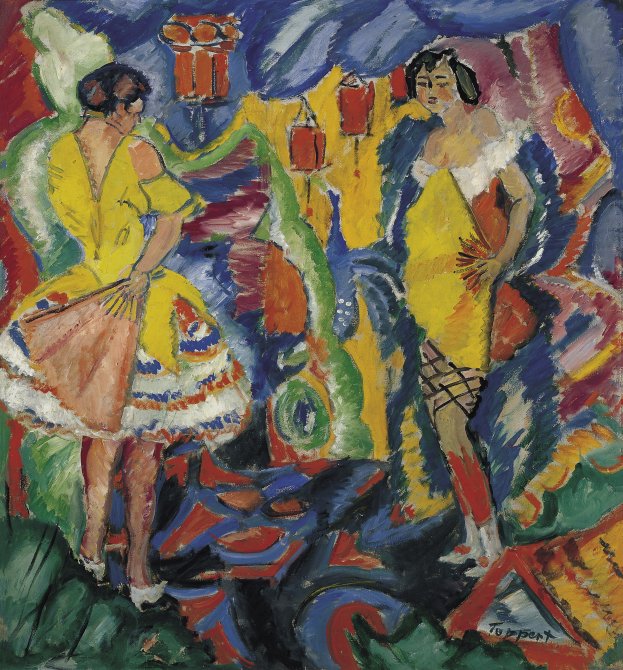

Georg Tappert

Varieté

ROOM H

We have seen paintings that show how the late 19th-century painters took an interest in the shows that filled Parisian nights, from the Opéra Garnier to the venues on Montmartre like the Moulin Rouge. Now let us travel back to Germany in the early 20th century, to the place where many avant-garde movements emerged just a few years later, where the painters were also attracted to stages, at times in the venues of the less prestigious performing arts, the denizens of the night. These and other subjects in their paintings were closely related to the name “degenerate art”, the label that the Nazi regime gave them just a few years later.

Georg Tappert, who was close to the Expressionist painters from Die Brücke (The Bridge) and Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), painted this work, Varieté, in 1911, when these two Expressionist groups were just beginning to carve a niche for themselves in contemporary German Art.

Just as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec frequented the Moulin Rouge, Tappert was a diehard patron of the Wintergarten, the most popular variety show venue in Berlin at the time. Variety show refers to a kind of show that may contain music, dance, magicians, acrobats, comedians, erotic numbers and even the exhibition of female physiques or extraordinary animals. The origin of the term comes from the name of a venue which opened in Paris in the late 18th century, Théâtre des Variétés.

Therefore, we are once again gazing upon a popular form of entertainment frequented by night owls, where liberties that were rare in the conservative Germany of the early years of the century were permitted.

Tappert found his place in that world of freedom, and this is why he devoted one of his best works, brimming with colour and exuberance, to this dance number. He found the subject to be interesting as the theme of a painting, as proven by other paintings he made around the same time, in which the dancers wore more revealing clothing and covered their bodies with fans. In a painting dated a few years later, Betty, the dancer on the right, is portrayed by herself, covering her nakedness with a fan. During that period, Betty became the painter’s favourite model.

The Wintergarten was a huge theatre whose artists included the stars of the day, such as the Great Houdini and Charlie Rivel. It was in operation until it was destroyed in a bombardment in 1944. Other venues continue to carry on its name today.

Therefore, this is a painter who inhabited these places where music, dance and circus mixed in a climate of great freedom. And Tappert recreated that world in his paintings: clowns yet again dressed as the characters from the Commedia dell’arte, along with dancers, musicians…

Yet that new Berlin, where the artistic avant-gardes found such fertile ground, was about to change forever with the Great War just looming around the corner.

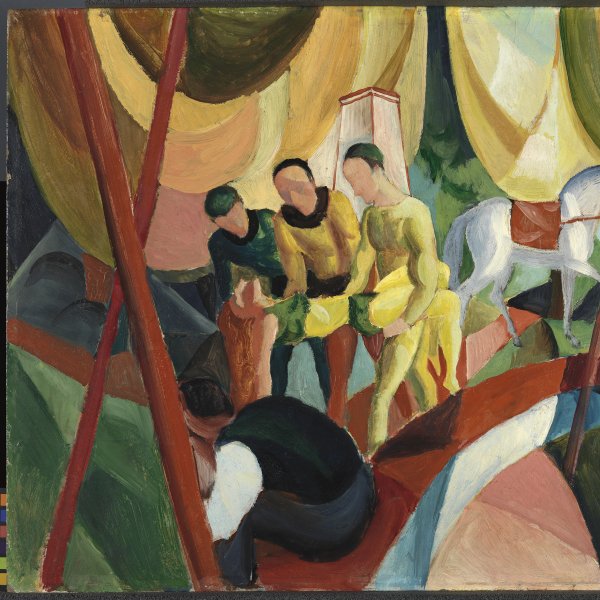

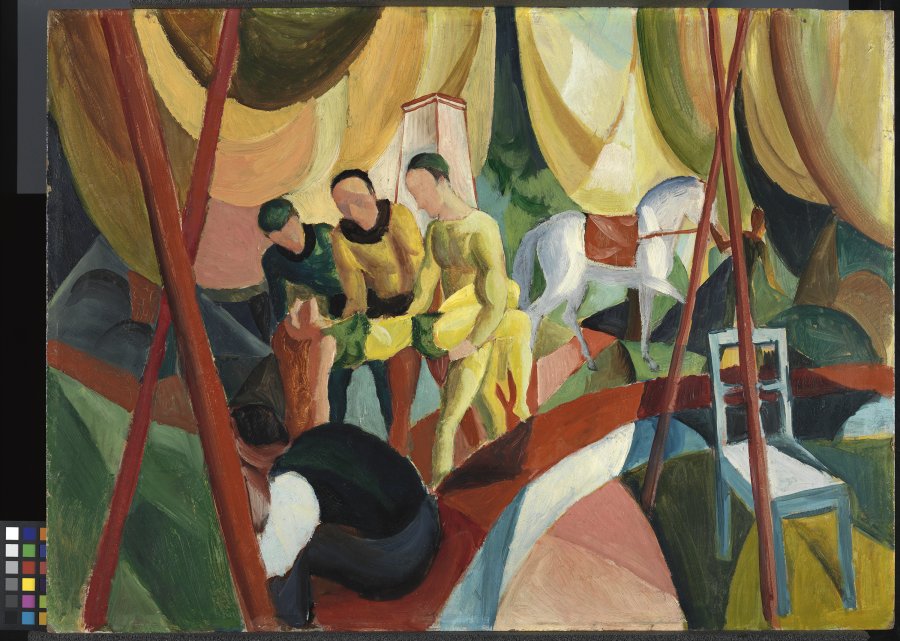

August Macke

Circus

ROOM 36

We just finished the section on Tappert with the words, “Yet that new Berlin, where the artistic avant-gardes found such fertile ground, was about to change forever with the Great War looming just around the corner”. Macke’s painting falls within these two bookends. August Macke was one of the leading members of the German Expressionist group The Blue Rider, and his life ended at the front in September 1914. But just one year before then he painted this work, Circus, a painting with a dramatic them and all the colour and beauty inspired by his recent encounter with the painter Robert Delaunay in Paris in 1912.

What was the circus to a German in the early 20th century? At that time, circuses could be travelling shows performed before audiences in tents that could be set up and taken down, or alternatively shows in large stationary venues that were just as luxurious as the best theatres ensconced in privileged locations in cities, which offered not only circuses but also perhaps concerts. Today in Spain this kind of building still stands in Albacete and Murcia, among other cities. The difference with the theatres from that era was the main ring, which was circular, a shape that became popular in the late 18th century because of the pre-eminence of numbers featuring horses. The écuyers, riders who did acrobatics on horseback and showed off their dressage skills, became stars in the 19th century. Madrid had the Teatro Circo Price, founded by the Irishman Thomas Price on Paseo de Recoletos; from 1880 until one century later, it occupied the site on Plaza del Rey where one of the Ministry of Culture buildings now stands.

In those early years of the 20th century, the circus was the place of everything different, the place of people who were dif- ferent, too. As mentioned when discussing Tappert, it was a period when variety shows might still mix magicians, acrobats and what we might call “sideshow acts” today, like the tallest or shortest man in the world, the strongest woman… Franz Kafka wrote The Hunger Artist around the same time, the story of a man whose show consisted in beating the fasting records in full public view. In fact, this existed in Spain as well until the 1920s.

Macke himself felt like one of the different ones, and this is why he focused on the world of the circus in some of his paintings. Just as Forain and Degas watched their dancers, in this painting Macke watched the circus performers, special beings who sparked his fascination. Thus, what he depicts is not a show but his life. The tragedy of the female écuyere who has fallen from the horse, her mates carrying her away in their arms, the despondent man who cannot hide his sorrow over the accident… The contrast between the bright colours of the circus – critics consider this work a masterpiece of colour – and the always unexpected tragedy, the coexistence of beauty and drama, lead us to think that from the avant-garde, Macke was engaging in a dialogue with the classics, with the pathos of some descents from the cross, for example. We once again cease seeing the pure beauty of the show to see the life behind the scenes.

Giacomo Balla

Patriotic Demonstration

Not on display

To the Futurists, movement was life. This is why the paintings by Giacomo Balla seem to try to capture colour in motion, fierce, furious motion. This group of avant-garde artists, led by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, loved modernity, speed and violence. During that time of war, Balla painted his Patriotic Demonstration while he was working with Picasso to make the sets for the ballet Parade, with a libretto by Jean Cocteau, music by Erik Satie and choreography by Léonide Massine. The ballet was a production of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, and it premiered in Paris in 1917.

That same year, Balla offered yet another example of his commitment to the avant-garde performing arts when he took charge of the stage sets and mise-en-scène of a “dancer-less ballet”, with Igor Stravinsky’s music piece Fireworks; a brief avant-garde show lasting a little over five minutes which premiered in Rome in the Costanzi Theatre, currently the Opera Theatre. The ever-changing coloured lights and motion of some of the set elements were the way he created movement in that dancer-less ballet, which was truly ground-breaking at the time.

A lot of material on this ballet has been found in Balla’s archives, including three tempera sketches for the complete stage, 35 designs of the unique constructions and one page with the 49 locations of the spotlights. With these materials, the Italian painter and sculptor Elio Marchegiani has made successive reconstructions of the ballet, the most recent one at Milan’s Palacio Real in 2009 for a show on Futurism.

The year is 1917, so entrusting the show to technology was a major risk. And, in fact, we know that the premiere was a disaster because of a short-circuit. Years later, several reconstructions of what it must have been like were undertaken, since only those attending the dress rehearsal had been able to enjoy it. They included the great choreographer Massine, an admirer of Balla and the first proprietor of the painting now owned by the Museo Thyssen.

Marc Chagall

The Grey House

ROOM 40

This painting transports us to Vitebsk, the Belarussian village where Marc Chagall was born, and where the roots of his pictorial imaginary and his relationship with the performing arts run deep.

Marc Chagall is one of the painters who makes us dream, and dreaming, as Sigmund Freud pointed out, is a human activity which shares many features with theatre. A very long life devoted to painting and punctuated with encounters with the performing arts may be partly explained by the painter’s origins, which were closely associated with the theatre. The teachings of Léon Bakst, a fellow Jewish painter (their original names were Lev Rosenberg and Moishe Segal), were very important to Chagall. In 1899, Bakst had founded a magazine (Mir Iskusstva) with Sergei Diaghilev. When Diaghilev created the Ballets Russes in 1907, Marius Petipa, one of the best dancers from the Mariinsky Ballet, was his choreographer, and Bakst designed the stages and costumes for many of its productions. Bakst actually participated in 19 productions of the Ballets Russes until shortly before Diaghilev’s death in 1929, after which the company folded. When this adventure began, Bakst had a disciple who was a mere 20 years old, Chagall, who had just arrived from his tiny village in Belarus. Shortly thereafter, Chagall took his first leap to Paris. In his memoirs, the painter acknowledges Bakst as the bridge between his village and the capital of France, where he arrived in 1909, the same time as the first tour of the Ballets Russes.

The Great War broke out in 1914, and Chagall went back to Russia. This is when he reencountered his roots in Vitebsk, as shown in the painting The Grey House, but it also marks the start of his commitment to the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and his first work as a revolutionary set designer filled with new ideas. Nikolai Evreinov invited him to design the sets for A Totally Happy Song. To make the backdrop, he referred to a painting he had made in Paris a few years earlier, The Drunkard, and he painted the actors’ faces and hands green and blue. Shortly thereafter, the Hermitage Theatre in Saint Petersburg (then Petrograd) commissioned him to make the sets and costumes for a performance of pieces by Nikolai Gogol. But Chagall’s place was his little village, Vitebsk, the site depicted in this painting. There, something very important for Chagall was created based on popular traditions: the Terevsat, the Theatre of Revolutionary Satire. It was run by an actor named Marc Razumny, and Chagall worked there as the artistic director in around 20 performances. Chagall found the roots of his dreams in this quest for tradition.

Chagall’s relationship to the performing arts continued his entire life. Perhaps the most famous sign of this passionate relationship is the ceiling of the Grand Opera in Paris, which he painted in 1964.

Pablo Picasso

Harlequin with a Mirror

ROOM 45

Picasso, perhaps the most important artist of the 20th century, has a prominent presence in the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, with seven paintings. The most celebrated one is this mysterious Harlequin.

We have already seen how those characters from 16th-century Italian theatre populated the artistic imaginary in the ensuing centuries, and how Pierrot and Harlequin become the icons of the avant-garde artists in the early decades of the 20th century. Their costumes had gradually spread to the world of the circus, so the painters from these movements found a twofold source of inspiration in those figures. And we already mentioned that the circus held a particular fascination for the avant-garde artists of that time.

When he painted this work, Picasso had been living in Paris for more than 20 years; he was 42 years old and had become an essential touchstone in several different painting movements, especially Cubism. When World War I was over, he took a trip around Italy with his friend Jean Cocteau, a poet, painter, filmmaker and playwright. This journey prompted Picasso to sense a need for a change. He went back to figuration, leaving behind Cubism, in which he had been immersed since 1907, when he unveiled his celebrated Demoiselles d’Avignon.

In this new period, which has been dubbed his “classical” period, when he depicted human figures with large volumes, resembling giants, Picasso revisited a theme that had been the subject of many of the paintings in his Rose Period (1904-1907), circus artists like jugglers and clowns… usually looking miserable and dressed in the old costumes of the Commedia dell’arte. Picasso painted this series inspired by real people, a troupe of artists encamped at that time in Paris’ Les Invalides. Those three years were peopled with harlequins, for whom he felt such an attraction that he even painted his son dressed as one. Furthermore, during the same years when Picasso was finishing Harlequin with a Mirror, he also painted several portraits of his friend Jacinto Salvadó, a young Catalan painter, dressed in a harlequin costume that belonged to Cocteau.

This painting is entitled Harlequin with a Mirror, but we all recall that Harlequin was dressed in colourful clothing patterned with multicoloured diamonds on his torso, arms and legs. This is how Picasso painted him in many of his works from his Rose Period. What we can recognise here is Harlequin’s hat. So who is this figure trying on Harlequin’s hat in front of a mirror? Perhaps Pierrot, envious of the joy and blitheness of his fellow character? The white surface on the left may be the Moon, Pierrot’s companion. His mood as a melancholy giant may lead us to this idea. But his costume is not what Pierrot wore either. He might be one of the many acrobats that Picasso had painted during that period filled with circus figures. So a young man wearing an acrobat’s clothing with the melancholy look of Pierrot is trying on Harlequin’s hat.

Today we know that at first, Picasso had planned to make this painting as a self-portrait; in fact, the painter’s face is concealed under the face that we see. So it was Picasso himself trying on the hat of the mischievous, fun-loving Harlequin, the master of mirth, in front of the mirror. Some scholars think that the melancholy acrobat yearning for Harlequin’s gaiety actually depicts the painter’s own sense of melancholy after a failed romance in the summer of 1923.

Twenty years later, those jugglers encamped in Les Invalides, his visits to the Medrano circus with friends like Max Jacobs and Apollinaire, and the memory of an opera that impressed him seemed to remain in Pablo Picasso’s imaginary. That opera was, of course, Pagliacci by Ruggero Leoncavallo.

It is worth recalling that Picasso, a painter and sculptor, was also a set and costume designer. He worked for some of the most important dance performances of Diaghilev’s famous Ballets Russes during that time, including Parade, with music by Satie, libretto by Cocteau and choreography by Massine, whose subject was the parade of a circus troupe; The Three-Cornered Hat, with music by Manuel de Falla based on the novel by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón; Cuadro Flamenco, featuring Flamenco dancers and singers-songwriters; and Pulcinella, with music by Stravinsky and libretto and choreography by Massine, clearly based on the Commedia dell’arte.

As you can see, the same friendship with Cocteau which led Picasso to paint this Harlequin with a Mirror also led him to work passionately for the stage for years.

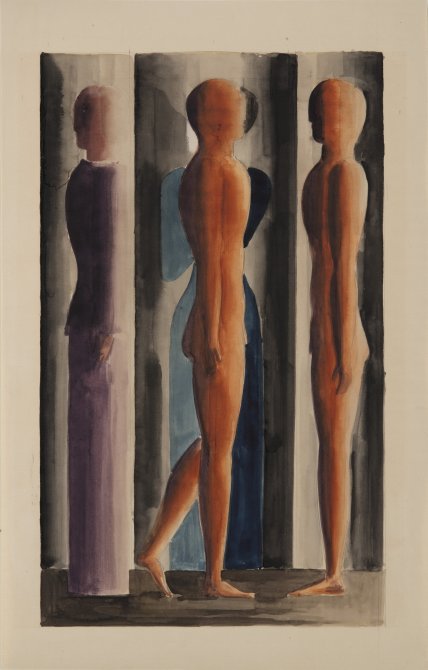

Oskar Schlemmer

Formation.Tri-partition

Not on display

One of the strongest points of the Thyssen collection is its fascinating look at the avant-gardes in the years between the World Wars in Europe, the two decades from 1918 to 1939. At several points during this historical period, works were made in which the performing arts served as the point of convergence for artists from different disciplines.

The Bauhaus is one of those points of convergence. In German, Bauhaus literally means “building house”, and this word was the abbreviated name of the Staatliche Bauhaus, or School of Building. The Bauhaus was the school in which Walter Gropius had founded the School of Applied Arts and the School of Fine Arts in 1919, which lasted until the triumph of Nazism in 1934. The course of the last four years of its existence was determined by its new director, Mies van der Rohe. The idea of fusing the arts and recognising the trades led artists like the painter and sculptor Oskar Schlemmer and the Hungarian expert in photographic art László Moholy- Nagy to work with this school.

Schlemmer was in charge of bringing to canvases – but also, or even more importantly, to stages – new ideas on the relationship between human beings and space. Hence the study of the geometric shapes in the human body, which he carried out in parallel to his fellow Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico.

Schlemmer created a show, the Triadic Ballet, which could be regarded as one of the icons of the Bauhaus and, by extension, of the avant-gardes from those years. It premiered in 1922 in Stuttgart, with music by Paul Hindemith. The performance was inspired by Arnold Shoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (based, in turn, on poems by Albert Giraud; as we may see, the shadow of Pierrot still persists), which premiered in 1912. The Triadic Ballet’s ambition was to become the benchmark of “total art”, a merger of the performing arts, music, forms of painting and sculpture…

The number three, which is full of symbolic meanings, is the crux of this performance: three acts, three performers, twelve choreographies and eighteen costume changes. These eighteen costumes became particularly celebrated, so much so that the costumes from this show have become the subject of several exhibitions throughout the century and are today housed at the State Museum of Stuttgart, which has an astonishing collection of works by Schlemmer. These costumes have been reproduced and imitated through the entire century and today are part of art history. Just to cite an example, one of the most fondly recalled shows by Spain’s Compañía Nacional de Teatro Clásico is its interludes on Cervantes directed by Joan Font in 2000.

The Triadic Ballet has been the subject of countless revivals that have striven to reproduce that show as accurately as possible. For example, there is a film lasting half an hour made in the 1970s with choreography by Margarete Hasting, Franz Schömbs and Georg Verden. Anyone who watches this piece will recognise in it not only the forms from this watercolour by Schlemmer but also other works by similar artists who were associated with the Bauhaus’ activities, such as Moholy-Nagy, three of whose works the Museo Thyssen owns, and his fellow Hungarian Sándor Bortnyik, whose painting The Twentieth Century bears a clear relationship with Schlemmer’s ideas and forms.

Sándor Bortnyik

The Twentieth Century

Not on display

One of the strongest points of the Thyssen collection is its fascinating look at the avant-gardes in the years between the World Wars in Europe, the two decades from 1918 to 1939. At several points during this historical period, works were made in which the performing arts served as the point of convergence for artists from different disciplines.

The Bauhaus is one of those points of convergence. In German, Bauhaus literally means “building house”, and this word was the abbreviated name of the Staatliche Bauhaus, or School of Building. The Bauhaus was the school in which Walter Gropius had founded the School of Applied Arts and the School of Fine Arts in 1919, which lasted until the triumph of Nazism in 1934. The course of the last four years of its existence was determined by its new director, Mies van der Rohe. The idea of fusing the arts and recognising the trades led artists like the painter and sculptor Oskar Schlemmer and the Hungarian expert in photographic art László Moholy- Nagy to work with this school.

Schlemmer was in charge of bringing to canvases – but also, or even more importantly, to stages – new ideas on the relationship between human beings and space. Hence the study of the geometric shapes in the human body, which he carried out in parallel to his fellow Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico.

Schlemmer created a show, the Triadic Ballet, which could be regarded as one of the icons of the Bauhaus and, by extension, of the avant-gardes from those years. It premiered in 1922 in Stuttgart, with music by Paul Hindemith. The performance was inspired by Arnold Shoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (based, in turn, on poems by Albert Giraud; as we may see, the shadow of Pierrot still persists), which premiered in 1912. The Triadic Ballet’s ambition was to become the benchmark of “total art”, a merger of the performing arts, music, forms of painting and sculpture…

The number three, which is full of symbolic meanings, is the crux of this performance: three acts, three performers, twelve choreographies and eighteen costume changes. These eighteen costumes became particularly celebrated, so much so that the costumes from this show have become the subject of several exhibitions throughout the century and are today housed at the State Museum of Stuttgart, which has an astonishing collection of works by Schlemmer. These costumes have been reproduced and imitated through the entire century and today are part of art history. Just to cite an example, one of the most fondly recalled shows by Spain’s Compañía Nacional de Teatro Clásico is its interludes on Cervantes directed by Joan Font in 2000.

The Triadic Ballet has been the subject of countless revivals that have striven to reproduce that show as accurately as possible. For example, there is a film lasting half an hour made in the 1970s with choreography by Margarete Hasting, Franz Schömbs and Georg Verden. Anyone who watches this piece will recognise in it not only the forms from this watercolour by Schlemmer but also other works by similar artists who were associated with the Bauhaus’ activities, such as Moholy-Nagy, three of whose works the Museo Thyssen owns, and his fellow Hungarian Sándor Bortnyik, whose painting The Twentieth Century bears a clear relationship with Schlemmer’s ideas and forms.

Edward Hopper

Hotel Room

ROOM 45

A woman seated on the bed in a hotel room holding a piece of paper in her hands. It is such a simple image, yet it is laden with such a powerful sense of drama, just like all Hopper paintings. It is hard not to imagine this room as the place of a scene from the best American theatre of the 20th century, from Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams to the latest by Sam Shepherd.

Hopper always seems to want to tell a story. Few painters take such a theatrical stance towards what they are looking at. That magical ability to capture moments in which one senses that the character is sighing, a musical silence between two notes… that instant laden with truth has inspired playwrights to pen plays that could take up residence in Hopper’s paintings. In 2006, the American playwright Douglas Steinberg premiered the play Nighthawks at the Kirk Douglas Theatre in Los Angeles, based on the painting of the same title that Hopper made in 1942. Several works based on Hopper paintings are known in the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany. Among Spanish authors, we could cite the Teatre Nacional de Catalunya’s 2010 premiere of the production of the Eva Hibernia play, La América de Edward Hopper (Edward Hopper’s America), which explores that same referential world as the American painter’s works. More recently, the book Summer Evening by Javier Vicedo Alós was published in 2015, which develops a series of difference scenes that happen in the Hopper painting by the same name. This play earned Vicedo Alós the Calderón de la Barca National Prize in 2014.

There is no room in this text, nor even in a regular-length book, to list the hundreds of productions whose stages have been inspired by Hopper, more or less accurately. Just as a sample, we could cite the mise-en-scène of the version of Rigoletto put on by Jonathan Miller for the English National Opera, in which he turned the quartet in the painting Nighthawks into the celebrated quartet in the Verdi opera.

We find it telling that Professor Walter Wells entitled his celebrated biography Silent Theatre: The Art of Edward Hopper. It is even less surprising that in her book Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography, Gail Levin tells us about his love of the theatre since his formative years, and even lists the productions that the painter attended in the 1920s with his wife, Josephine, who posed for this painting. Levin also recounts the origin of this painting, which brings us back to a name that we have already found on our journey: apparently Hopper based it on a drawing by Forain that appeared in a magazine.

Hotels and theatres as scenes of desolation. Few painters have used theatres as an arena to show the sense of solitude characteristic of contemporary humans. Those coliseums used for cinema, music, opera, dance and variety shows are terrifying when empty: Two on the Aisle (1927), Sheridan Theatre (1937), New York Movie (1939), Girlie Show (1941), First Row Orchestra (1951) and Intermission (1963), just to cite a few of the more celebrated ones.

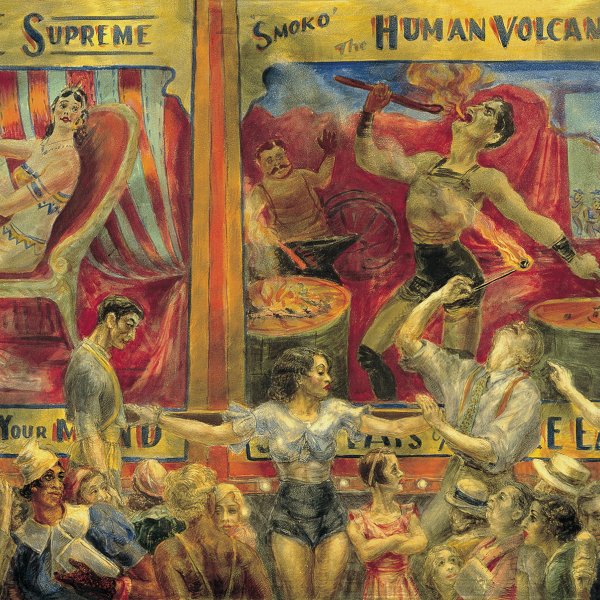

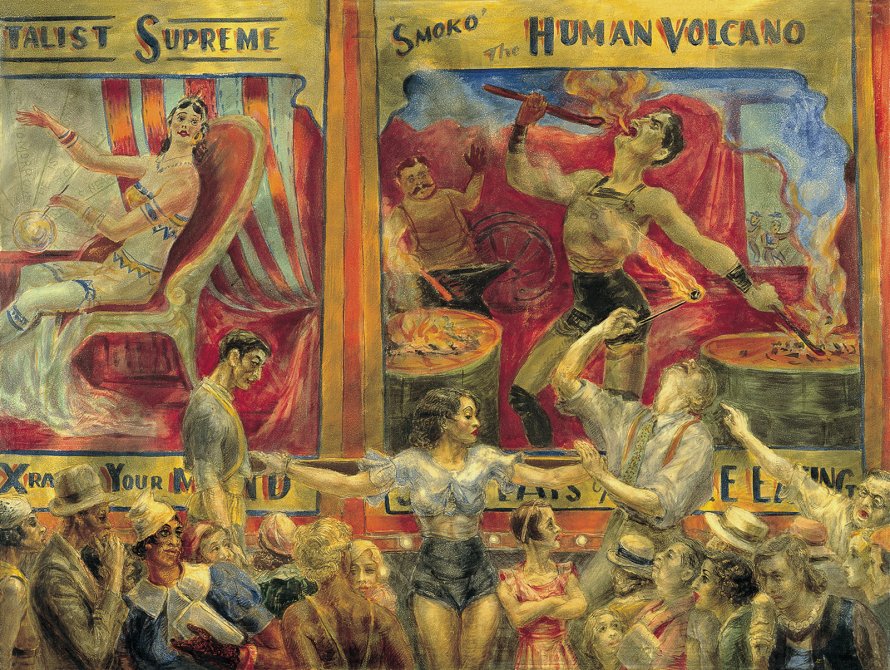

Reginald Marsh

Smoko. The Human Volcano

ROOM J

One of the characteristics that distinguishes the Thyssen collection from any other museum in Spain is its attention to American painters. In our journey, we inevitably come upon two great names in US painting in the 20th century who share quite a few similarities: the presence of Europe in their training, their work as illustrators at the most prestigious New York magazines, their forays into stage design, and their attraction to the world of low-brow shows. These artists are Reginald Marsh and Walt Kuhn.

Marsh, an American who was born by chance in Paris in 1898, the same year as Federico García Lorca, was educated at Yale. He was an illustrator for the Daily News, The New Yorker, Esquire, Fortune and Life, as well as a theatre set painter and a teacher. His paintings have one essential feature: he paints people. On the beaches, on the streets, at dances, on fair rides, in popular shows like the cinema, in variety shows such as circuses and even in those dance marathons depicted in the Horace McCoy novel They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?, which was turned into a film by the same name. In short, the working class in the Depression in the United States. The people on Coney Island, the amusement park in New York’s borough of Brooklyn. Cheap entertainment. Based on his first commission for Vanity Fair magazine, that place became his way of seeing the world.

In her note for the Thyssen collection catalogue, Gail Levin tells us about Marsh’s attraction to Coney Island: “He explained his reaction to Coney Island in the following terms: ‘I’ve been going out there every summer, sometimes three or four days a week. On the first trip each summer I’m nauseated by the smell of stale food, but after that I get so I don’t notice it. I like to go there because of the sea, the open air, and the crowds-crowds of people in all directions, in all positions, without clothing, moving-like the compositions of Michelangelo and Rubens’”.

What is Marsh showing us in this painting? People strolling; some are watching, others are eating ice cream, and yet others are trying to attract the public to the fire-eater’s show. An advert for a fortune-teller is on the stand next door. In the centre, we see a woman who is wearing shorts similar to those worn by the man in the poster. We see a man who resembles the man in the poster, whose clothing makes him stand out, watching the other man with a smirk. We may think that Smoko is challenging the curious onlookers to try eating fire, and one passer-by wearing a shirt and tie is trying to emulate him. We can hear the hustle and bustle and feel the heat. And we may recall those comedians, those Harlequins, Colombinas and Mezzettinos who performed before the public on a platform a metre and a half off the ground in the Carnival in Ostend as painted by James Ensor in 1908.

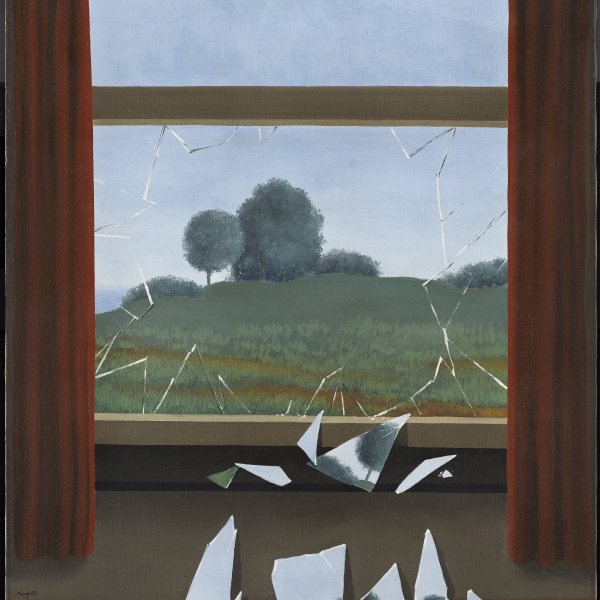

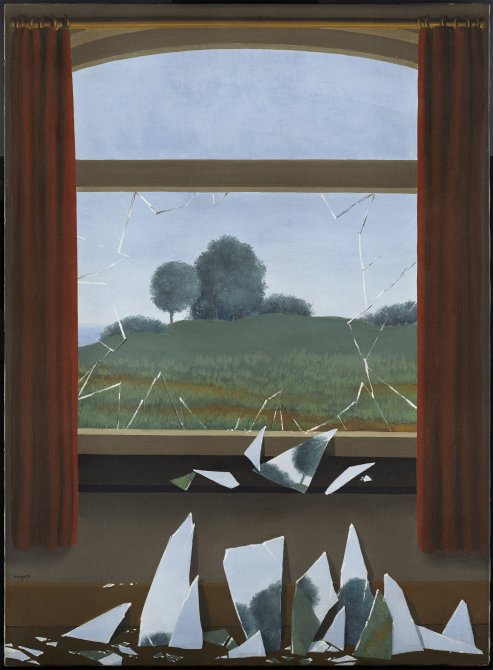

René Magritte

The Key of the Fields (La Clef des champs)

Not on display

“The curtain is opening”, “the curtain is being raised”… theatres that still use what we call a stage curtain to hide the stage from the public eye until the action begins tend to open them in one of two ways: the German curtain, which is raised towards the flyloft, that is, towards the rigging above the stage, and the American curtain, which is split in two and opens out towards either side. We are sharing this information, which may seem superfluous, because we know that it is not. A few years ago, the author of this text read a critique of a play from which one could deduce that the critic thought that the curtains were rolled up like roller blinds. So in the theatre, opera or dance, they still say “the curtain is opening” or “the curtain is being raised”. Magritte painted many works which somehow suggest the presence of an American-style curtain. He often played with the resemblance between the curtains framing a window and the curtains on a stage to show us a reality that was and yet was not real, the basic thinking behind his artistic output and the very foundation of the performing arts: what you are seeing onstage seems like life, but it is not life.

The painting La Clef des champs plays with us starting with the title itself, which is one of those French expressions whose initial referents have been lost from the language, so its meaning seems obscure: it is and yet is not what it means. Today, the French prendre la clé des champs (literally: taking the key of the fields) means ‘to free oneself’, ‘to head for the hills’ in the quest for freedom. Some scholars believe that the expression was originally claie des champs, with a claie being a stone wall that divides land owned by different people, just like travailler pour le roi de Prusse was transformed into travailler pour prunes, but it still means ‘to work for peanuts’.

What we see here is a window which is actually not a window but a painting of the reality beyond the window. Just like many of Magritte’s works, the painting harbours a reflection on what actually is and what we perceive, something that we can find constantly in theatre from Calderón to Pirandello. Perhaps for this reason, Magritte’s imaginary has been populating stages for decades. As soon as we look at photographs of mises-en-scène in from recent years, we find many stage designs that are reminiscent of Magritte works, from Dublin, London and Paris to southern Australia, not to mention dozens of cities in the United States. We can even find shows that are directly inspired by the paintings of this Belgian artist. In Spain, too, we can see Magritte’s influence in shows like Nubes by the company Aracaladanza.

A Magritte exhibition inspired Tom Stoppard to write his play After Magritte in 1970, just a few years after his first hit, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead. The author of celebrated plays like The Coast of Utopia – known popularly for being the scriptwriter of Shakespeare in Love – found Magritte’s universe to be fertile ground for that world that his writing occupied in those early years: a world in which everything is sleight-of-hand, where everything is a dream, where we live a truth that both is and is not true. Pure theatre. After Magritte was published in Spain in 1972 and has been performed in both Spanish and Catalan. It would be an outstanding complement to any exhibition on this quintessential 20th-century painter.

Before closing, we would like to mention yet another minor yet curious relationship between Magritte and the performing arts: Le prêtre marié, those masked apples that Magritte painted in 1961, which no doubt inspired the artist Joan Brossa when he designed the celebrated trophies for the Max Theatre Awards.

Walt Kuhn

Chico in Top Hat

ROOM J

Just like zoffany and Toulouse Lautrec, Kuhn was at once a witness of and a publicist for the performing arts. Just like the former, he felt attracted by this world, and his works were used to advertise it. Kuhn was a New Yorker of German extraction who came back to Europe to train and then returned to New York to work as an illustrator and caricaturist in magazines like Puck, Judge, Life and New York World. During that time, he also began to work as a poster designer and set and costume designer for musical theatre. In 1928, he even designed the costumes and sets for the show Merry-Go-Round at New York’s Klaw Theatre, which featured the star of that era, Libby Holman. It was a world he had been familiar with from a very young age, when he was in charge of carrying the costumes from the workshop where he worked to the different theatres. That world, in which the boundaries between theatre, opera, variety shows and circus were not so clearly drawn, became the main theme of his work as a painter. In the 1920s, he began to paint his portraits of circus and variety show figures, which he continued until his death in 1949.

And what we have here is a new Pierrot, a modern whiteface2, even more modern than Kuhn’s 1929 White Clown, which is in the National Gallery in Washington. Chico is his name, because Kuhn portrayed real artists whom he knew well. In addition to this painting, Kuhn made two other portraits of Chico. In one of them, he is wearing a more classic whiteface clown costume. In the other, he is dressed the same as in this one, but we can see his entire body; he is kneeling with his left side facing us. His enormous hands placed over his thighs are impressive. His look is harder than in this portrait. Kuhn painted these three portraits of Chico in 1948, one year before his death.

It is obvious that Chico is not just another whiteface. There is something like a lost, melancholy look in his eyes, but his costume would be more typical on a Ringmaster, the clown who also serves as the master of ceremonies. Yet most importantly, we are disturbed by his beauty, his gauntness, his large blue eyes, the charm of his hat jauntily pushed back. As we said above, another portrait in which he is wearing the same costume shows a harsh, almost violent gesture, which transforms his expression.

We find him disturbing. He conveys melancholy, but that is not all. We know that Kuhn spent the month of February 1948 in a circus in Sarasota, Florida, drawing and painting its inhabitants, who were spending the winter getting ready for the next tour. We know that at that time his personality had started its definitive freefall in a strange kind of disorder: he was quarrelling with everyone, bought a gun, had to be admitted into a clinic… and he died less than one year later from a gastric perforation.

In the last years of his life, Kuhn had painted a large number of portraits of circus folk, including clowns, tightrope walkers and acrobats. Only four of them have a name: Chico, the trapeze artist Roberto (another of his masterpieces, which became the most expensive painting by a living American painter in 1945), and two very famous comedians: Bert Lahr, an actor whom everyone recalls as the Cowardly Lion in the film version of The Wizard of Oz, who was also a hit at that time with the show Burlesque, and Bobby Barry, a legend in revues from the 1920s who worked with Lahr in Burlesque. But unlike Lahr and Barry, he did not paint grandiose figures at the peak of their art or fame. Instead, he depicted them in a neutral space, looking at the viewer, far from the spotlights and noise. In all of these portraits, the sitters’ looks are startling. Perhaps one of these years the Museo Thyssen will treat us to an exhibition on Walt Kuhn which is sure to be unforgettable.

Richard Lindner

Moon over Alabama

ROOM 52

Our third american artist was born and educated in Germany. He was born in Hamburg in 1901 to a Jewish father and an American mother, but Nazism forced him to emigrate first to France in 1933 and then to the United States in 1941. This nationalised emigrant would become one of the great icons of Pop Art in this country. His paintings are immediately recognisable and are part of an imaginary which has been shared and spread around the entire world.

When he reached the United States, he moved to New York and worked as an illustrator for the magazines Fortune, Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. As we can see, New York magazines are essential to understanding the fine arts in the United States. In Lindner’s case, it was not a job he combined with painting but instead perhaps a pathway to reach painting. He gradually tapered off illustrating magazines and in the 1950s finally devoted himself fully to painting.

Curiously, his paintings reflect motifs that he was familiar with in the Germany of his youth, perhaps from artists like George Grosz or in plays like the ones by Bertolt Brecht with musicians like Kurt Weill and Hanns Eisler: gangsters and prostitutes. Always that sordid world, with the contrast of lively, crackling colours.

Alabama Song is another of those scenes, a gangster and a prostitute crossing paths on the street. So what does this have to do with the performing arts? The clue comes from the title of the painting. Alabama Song is a song with lyrics by the playwright Bertolt Brecht and music by Kurt Weill from their opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny. Jenny and the girls reach the city of Mahagonny, in the middle of the desert, ready to work as prostitutes. “Oh, show me the way to the next whiskey bar / Oh don’t ask why, oh, don’t ask why! / For if we don’t find the whiskey bar / I tell you we will die. / Oh, moon of Alabama, we now must say good-bye / We’ve lost our good old mamma / And must have whiskey, oh you know why. / Oh, moon of Alabama, we must now say good-bye”. The opera did not reach the United States until 1971, years after Linder had painted this work. The song became popular in the 1960s, and singers like Jim Morrison and David Bowie sang very popular covers of it.

So this apparently simple painting shows us an émigré’s view of the world in which he was fated to live. Yet it also speaks to us about a painter who is attentive to the signals from the streets he walks and does not forget his cultural referents, both those related to painting and those related to the performing arts, painting and performing arts which show a critical take on his world. Some critics also believe that the reference to Alabama is related to the race conflicts and the civil rights struggle, much of which transpired in Alabama in 1963.

Renato Guttuso

Caffè Greco

Not on display

Throughout this tour, we have examined paintings from artists who watched as their works were branded “degenerate art”. The 1930s and 1940s were often horrible for many European artists, who were forced to leave their countries, go into exile or were even murdered…

During World War II, Renato Guttuso belonged to the anti-fascist resistance. When the war ended, Guttuso took on the personal mission of winning back his place in Italian art and, by extension, European art. He became one of the main players in the Italian cultural Renaissance which produced major works in all the arts in the 1950s and 1960s. Politically committed in the 1930s, he was connected to Spain by his 1938 painting Execution by the Firing Squad in the Countryside, which he dedicated to Federico García Lorca in 1938 and which today belongs to the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna in Rome. Guttuso used painting as a political weapon, but also as a way of recording the memory of his country and, on a more personal level, of his teachers. After the 1960s, his own memory began to figure more prominently in his works.

There are two main versions of this painting, Caffè Greco, in addition to several preparatory sketches. In it, a character associated with the performing arts appears in the centre. In the painting displayed in the museum of Cologne, which is the definitive version, this gentleman who interests us on our tour is in the rightside corner.

In an article, Guttuso recounted how he got the idea for this painting. He was sitting in the famous Caffè Greco in Rome, a legendary spot through which Europe’s entire intelligentsia had filed since the late 18th century. At the time, it was filled with young people and tourists. And he imagined the painter Giorgio de Chirico, whom he admired, on the right side. It occurred to him to fill the venue with past and present figures in order to pay tribute to his teacher and friend, who is sitting on the left side of the painting. We cannot fail to mention that De Chirico designed sets for the Krull Opera of Berlin, just like other artists who shared his imaginary, such as Schlemmer and Moholy-Nagy. They sought to recognise one of the most important actresses in the history of Italy, Anna Magnani. Even though she worked in theatres in Rome and Milan for twenty years, today Magnani is famous for her work in the cinema, with memorable films like Bellissima and The Rose Tattoo.

But let’s look at the people sitting in the centre. It seems like a bizarre detail. They are Bill Cody, the celebrated Buffalo Bill, and a Navajo Indian. Buffalo Bill was a legend from the stories of America’s Wild West, a buffalo hunter for the army, a Union soldier in the Civil War, and an explorer of Indian Territory. Inspired by the shows touring the country, like the Ringing Bros. circus, he assembled his own called Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. It travelled around the United States and even toured several European cities, including Barcelona, where it was not very popular since the flu killed several of the Navajo Indians who were on tour with him. In the last decade of the 19th century, Buffalo Bill was possibly the biggest show business star in the entire world. And he sat down to have a drink in the Caffè Greco. Guttuso shows him to us with his more familiar appearance, seated next to a Native American who may be none other than Chief Sitting Bull, whom he had hired for his show.

We cannot leave this painting without mentioning yet another historical figure whom Guttuso included among the youths and Japanese tourists. At the table in the middle of the café is the French writer André Gide, a winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. Even though they were not the most important part of his oeuvre, Gide also write five plays, including Saul, King Candaules, Oedipus, Persephone and The Thirteenth Tree. Guttuso is thus paying tribute to a unique, free-spirited writer.

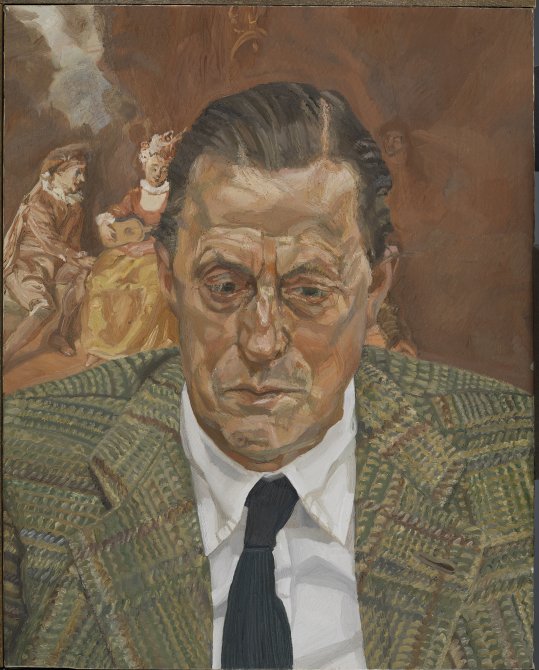

Lucian Freud

Portrait of a Man (Baron H.H. Thyssen-Bornemisza)

ROOM 49

We would have been hard-pressed to imagine such an interesting ending to this tour, even if we had planned it.

When seeing the face of Baron Thyssen, the collector who spent decades passionately yet patiently assembling this series of paintings we have visited, we would like to imagine the conversations between the sitter and his portrait painter over the course of the fifteen months that it took Freud to make this painting. A close friendship was sparked by those conversations in Freud’s London studio.

The Baron is somewhere else in this painting. Just like Ann Brown sitting for Johan Zoffany and Chico sitting for Walt Kuhn, the baron was facing eyes that would find the dark, sweet shores of melancholy in his gaze, and perhaps self-recognition in that defenceless Pierrot that Watteau had painted almost 300 years earlier. The baron had owned that painting which began this tour for five years. We can imagine that the two friends spoke about the painting he had bought in 1977, about the characters from the Commedia dell’arte, about the fêtes galantes and about Watteau’s technique. We could wonder whether it was Freud’s idea or the baron’s that this painting take a vantage point behind the baron’s head. We know that at times Freud played with the presence of other paintings within his own works, a custom ensconced within the European tradition. We also know that the small Watteau painting had impressed him and that he had made a copy of it. We know that it inspired one of his most celebrated paintings, Large Interior W11. A few years ago, the museum held an exhibition in which Freud’s modern version, the portrait we are looking at now, and Watteau’s painting were all displayed side by side. It is clear that the 1712 painting impressed Lucien Freud. However, if it is accompanying the sitter here, it is not as decoration, as a pure reference to painting, but instead it helped Freud portray the heart and soul of his sitter. The baron’s position, which covers the figure of Pierrot as if he sought to replace him, and that serious look that is not gazing forward, show a fragile image of a very powerful man, as if the sitter felt a yearning for what he had not experienced. There is no word in Spanish to describe that feeling except in the parlance of the Canary Islands: “magüa” – a sense of yearning for that felicitous intimacy, for finding one’s intimate place of joy in something simple. In this case, it is nothing less than in a conversation with one of the great painters of the 20th century in his studio in Notting Hill.

This was the first time that Baron Thyssen had posed for a portrait. The man who dreamt up this museum, this impressive art collection, wanted – or agreed – to go down in posterity with a simple portrait depicting his melancholia, along with a painting that speaks about joy, theatre and music. Throughout his decades of work as a collector, Baron Thyssen left us a small trace, a secret pathway, for using painting to view the ephemeral arts that occur on stages.

No doubt you now feel like going back to look at Watteau’s painting.