By Teresa de la Vega

“We owe much of our pleasure in looking at the world to the great artists who have looked at it before us,” wrote Kenneth Clark. the great British historian. Few activities are more enriching than travelling and looking at art, for these broaden our horizons and minds and nourish our spirit. They also enable us to meet others and get to know ourselves.

The gaze of the traveller — like that of the visitor to a museum — is curious and inquisitive. It is eager to discover new things of beauty and riddles to solve, and be enriched by views of unknown territories, the memories of which will last forever. Each new journey, each new artist discovered helps to open the doors of our perception, prompts new adventures, allows us to witness the diversity of human experience and helps to expand our awareness of our own identity.

Momentarily removed from the hustle and bustle of everyday life, we are transported by our thematic route through the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza rooms to a land (as in Baudelaire’s dream in Invitation to the Voyage) where “all is order and beauty, luxury, peace and pleasure”. Here there are countless surprises in store for the visitor and we hope that, like the inveterate traveller, he or she will want to come back to see more of the unusual routes and revelations awaiting those who return.

Tour artworks

Luca di Tommè

The Adoration of the Magi

ROOM 1

This panel was once part of an altarpiece predella. According to tradition, the Magi came out of the East on a long journey to pay homage to Jesus of Nazareth with gifts of a kind mentioned in the Bible in association with Solomon and hugely symbolic in themselves: gold representing Christ’s kingship, frankincense his divine nature and myrrh the human suffering he would endure.

Of the four Gospels, St Matthew’s is the only source in the Bible mentioning figures following a star in search of a “King of the Jews” born in Jerusalem. However, at no time does it suggest that these visitors were monarchs, for the original Greek refers to them as magoi, who were originally priests of Zarathustra among the Medes or Persians and were believed to possess the gift of interpreting dreams and predicting the future. The promotion of these scholars to kings is almost certainly due to the passage in Isaiah (60:3) in the Old Testament: “And the Gentiles shall come to thy light, and kings to the brightness of thy rising.” Furthermore, nowhere is it written that there were three, although that figure can be deduced from the number of gifts mentioned in the Gospel, assuming that each bore one gift.

Since ancient times and indeed until relatively recently, journeys were not undertaken for pleasure: the roads were infested with bandits and wild animals, the seas with pirates, nature was an essentially hostile environment. Instead, journeys were undertaken for religious reasons, such as pilgrimages, or for purposes of conquest or commercial gain.

Without doubt the most famous of all the routes was the “Silk Road”, a trading network between Asia and Europe which stretched from Chang’an (now Xi’an) in China via Antioch in Syria and Constantinople to the gates of Europe. Coined by the German geographer Ferdinand Freiherr von Richthofen in 1877, the term was used to denote the richest merchandise (silk-making being a closely-guarded secret known only to the Chinese) that travelled the route. But many other kinds of goods were also carried along its paths: fabrics, precious metals and stones (like amber), ivory, lacquer, glass, coral, manufactured materials, spices and aromatic substances like incense and myrrh (the gifts made to the Child by the magi).

Many spices (from the Latin species meaning “essential”) and fragrant resins are named in the Bible, as they played an important role in worship. Indeed, they were regarded as objects of great value: kings often exchanged them as gifts or the victors in war demanded them as tribute from the vanquished. However, not only goods were exchanged, but also ideas, artistic knowledge, languages and religions, for alongside the merchants and soldiers travelled scholars and monks representing the world’s great religions and these spread the teachings of Buddha, Confucius, Jesus Christ and Mohammed.

In 1324, some years before this panel was painted, the great traveller Marco Polo died. Marco Polo was the most famous (although not the first) European to travel the Silk Road. His fame is due to his description of an expedition in his book Il Milione (“The Million”), better known as The Travels of Marco Polo or The Book of the Marvels of the World.

In the 15th century, the navigation of new sea routes (ushering in the Age of Discovery) and the rise of the Turkish Empire led to a gradual decline in the importance of both the Silk Road as a main commercial artery between East and West and of some of the most vigorous and magnificent cities along the way. Forgotten by the outside world, these became shadows of their former selves.

Ercole de' Roberti

The Argonauts Leaving Colchis

ROOM 4

Originally from the decoration of a cassone or marriage chest, this small panel illustrates a scene from the story of the Argonauts — the Greek heroes who sailed with Jason on the quest for the Golden Fleece (the fleece of a winged ram with magic powers which was guarded by a dragon). It depicts the moment when Jason leaves Colchis with King Aeetes’ daughter Medea, who, having fallen in love with the hero, has helped him seize the fleece.

The name of the group, whose feats were related by various Classical writers (Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollodorus, Strabo, Ovid...), comes from that of the ship which took them on their adventures. Known as the Argo, its name was derived from Argus, who used wood from the sacred forest of Dodona to build it.

One of the oldest Greek legends, the story of the Argonauts has been suggested by some scholars as being previous to the Odyssey, although it did not exist in written form until centuries later. The travels of Ulysses are also assumed to have been based, at least partially, on that story, for in the course of his own travels Jason — like Homer’s hero — had to face not only the forces of nature, but also fabulous creatures (sirens, harpies, monsters...) and sorceresses.

Whatever the case, both epics contain elements commonly found in popular tales: an eventful journey undertaken by a hero, help from unlikely allies to attain an apparently impossible goal, etc. This is, then, a journey of initiation and pursuit of self-knowledge from which, after a series of ordeals, the main character emerges a hero.

Historical echoes have also been detected in the legend. The members of the expedition set sail from Iolcos in Thessalia and, having stopped over on the island of Lemnos, crossed the Hellespont — the strait separating Chersonesos from Asia Minor — to their destination. All this could well be a reflection of the voyages made by the Greeks in ancient times to colonise and open up the Black Sea area to trade.

The panel depicts the Argo as a cog with a rounded hull. This type of small mediaeval vessel (from the Flemish kok, meaning “shell”) first appeared in the 10th century and was used widely from the 12th century on. Normally built of oak, which was extremely abundant in northern Europe, cogs were fitted with a mast with a single square sail and used for maritime trade, especially in the Baltic Sea region, which was controlled by the powerful Hanseatic League.

Atop the mast was the crow’s nest, a wooden platform from which the sea could be scrutinised for enemy vessels and land sighted when nearing the destination, a task sometimes meted as punishment to seamen during voyages.

Titian (Tiziano Vecellio)

Portrait of Doge Francesco Venier

ROOM 7

When the small Adriatic lagoon settlement of Venice gained independence from the Byzantine Empire in the 9th century, so began the glorious history of a great maritime and commercial power.

In commemoration of their victory over the Dalmatian pirates who had incessantly harassed their ships, each year on Ascension Day the Venetians celebrated the Sposalizio del mare (a symbolic marriage between the Doge and the sea) aboard the richly adorned galley Bucintoro. During the event, the Republic’s chief magistrate would cast a ring into the water, while uttering the words: “We espouse thee, O Sea, in testimony of our perpetual dominion over thee.”

The short reign of the Doge whose portrait Titian painted was marked by the peaceful settlement of the Republic’s wars but also by a rise in the cost of living that affected the Doge’s popularity considerably. Although the scene in the painting with a sailing ship in front of a burning building, viewed through the window, has never been identified, it has been interpreted as a symbol of the city’s power.

Nevertheless, the rot had set in long before, with the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453. Eventually the overland paths monopolised by Genoese and Venetian merchants were cut off, forcing Europeans to seek new trade routes, their main aim being to find an alternative path to Asia to continue the trade in spices from the East and avoid the Ottoman-controlled Mediterranean. The discovery of America soon after, however, was to affect trade routes permanently and change the view of the world forever.

Claude Lorraine

Pastoral Landscape with the Flight into Egypt

Not on display

Claude Lorrain, who was one of the greatest exponents of 17th century Classical landscape painting, was active at a time when this type of art was becoming a genre in its own right. His greatest source of inspiration was the countryside around Rome. The subject of this painting is the Bible story of the flight into Egypt (Matthew 2:13-15), which tells how an angel appeared to Joseph in a dream and instructed him to flee to Egypt with the Virgin Mary and the Child Jesus, as King Herod had ordered all the male children in Bethlehem killed by his soldiers.

In the Apocryphal Gospels and subsequent Christian tradition, this story was elaborated with accounts of numerous events along the way and the journey itself was sometimes cited to draw a parallel between the exodus of the Holy Family and the plight of all those who are forced to flee their homelands or fall prey to political repression.

The real subject of this painting, however, is the idyllic Roman countryside. The amber light typical of the Arcadian scenery (so popular with 18th-century British painters and travellers), pervaded by a picturesque quality, inspired a device known as the Claude’s Glass — a tinted convex mirror often used by artists to produce images of landscapes in miniature and study the subtle ranges of tones in compositions. A similar though larger device was apparently often attached to horse-drawn carriages so that travellers could see the reflection of the scenery not as it actually was but as Claude Lorrain would have rendered it.

In areas as frequently visited by artists and travellers as the Lake District in England, special viewpoints were set up where tourists (armed with maps and Claude’s Glasses from opticians’ shops or art material suppliers) could turn their backs on the landscape to admire the view, duly framed and re-configured, in the manner of a 17th century work of art. Thanks to the distorted perspective, chromatic saturation and compressed tones in the reflection, it was possible to unify forms, although at the expense of a certain loss of detail. And as if by magic, Mother Nature suddenly became “picturesque” (i.e. “worthy of being painted”).

Canaletto (Giovanni Antonio Canal)

The Grand Canal from San Vio, Venice

ROOM 17

Over three hundred years ago, one of the epic journeys — the “Grand Tour” — came into being. Thanks to ever greater political stability in mid-17th century Europe, trade between nations increased, making it possible to travel for the sheer pleasure of seeing other places and coming into contact with other people. The so-called “Grand Tour” was an itinerary (and precursor of modern tourism) whose heyday lasted from the period mentioned above to the 1820s, when rail travel — by then much more affordable — became the alternative.

The Grand Tour, which could last for several months or even years depending on one’s means, was especially popular with young, upper-class Britons. As a prelude to marriage, it rolled relaxation, education and social self-promotion all in one, as it enabled travellers to see the splendours of Classical art and the Renaissance while affording them access to members of the European aristocracies.

Although its original purpose as a formative trip appears to date from the 16th century, when artists and humanist intellectuals travelled around Italy to familiarise themselves with Classical culture, the earliest reference to a journey of this type as a “grand tour” was apparently made by the Jesuit Richard Lassels, a traveller who in 1670 recommended an itinerary which he called “The Voyage Of Italy, Or A Compleat Journey Through Italy”.

Travellers usually visited Turin, Milan and Venice and then headed south for Florence. Rome was a must and drew large numbers of young people with artistic aspirations. The tour ended in Naples, where the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii, whose excavation began in the first half of the 18th century, could be admired. In Travels in Italy, published in the late 1780s, Goethe also popularised visiting Sicily.

The experience was often recorded in journals, as in the case of A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy by Laurence Sterne, or History of a Six Weeks’ Tour by the Romantic writers Mary and Percy Shelley. Furthermore, vedute or city views, like those by Canaletto on display in this room, became fashionable as souvenirs for travellers to take home.

Bartholomeus Breenbergh

Capriccio with Roman Ruins, Sculptures and a Port

ROOM 20

The Grand Tour route was greatly influenced by the German Hellenist Winckelmann, who made the custom of studying the history of Greco-Roman and Renaissance art while in Italy almost compulsory.

Winckelmann’s work was also important in that it fostered a new purism vis-à-vis decoration and architectural forms, in imitation of the archaeological remains found on Italian soil, and led to the dissemination of the Neo-Classical style. Whether discussing or depicting his scenes, the traveller uses his imagination to restore the vestiges of the past, with their auras of nostalgia that he has encountered along the way.

Ravaged by time and covered in vegetation, the ruins of the imposing Classical buildings symbolise the triumph of the passing of time over civilisation, and spur us to philosophical reflection on the vanity inherent in all human endeavour.

Matthias Stom

The Supper at Emmaus

ROOM 20

This scene by Stom captures the climax in a story from the New Testament. As two of the disciples were travelling the road to Emmaus, the resurrected Christ, whom they did not recognise, joined them. The painting depicts the moment when Christ blessed the bread — part of the sacrament of the Eucharist — and his companions suddenly realised who he was.

The idea of man as a traveller and life as a pilgrimage, a brief intermediate sojourn or a vale of tears is an existential concept common to many peoples and religions. Knights errant, wandering monks, nomads in pursuit of enlightenment, all in search of themselves on a physical and existential journey… To the hat he wears as protection from the elements, the figure on the left has attached a shell — the symbol of his pilgrimage. Stom’s work is an invitation to reflect on the law of hospitality for hospitality is that essential sense of fellowship uniting all those who make the journey.

Jan Jansz. van der Heyden

Corner of a Library

Not on display

Thanks to the great campaigns of exploration and voyages of circumnavigation, the world’s horizons began to recede at a dizzying speed and by the end of the 17th century the shapes and sizes of the continental masses and oceans had all, however approximately, been defined. It is true that huge areas were still terra incognita and hidden beneath a cloak of mystery, but not for much longer.

In the 18th century, the world took on a truly universal dimension, for it came to be perceived as a whole, as something “global”. The new scenario that opened up during the Age of Enlightenment triggered a series of intercultural contacts whose consequences were important for Europeans and native peoples alike. For the latter this meant the decline of their societies, while for the colonists such encounters often led to intense debate on the very nature of culture itself.

Corner of a Library depicts a room full of scientific instruments (a terrestrial globe and armillary and celestial spheres), several scrolled maps leaning against a bookshelf, an open atlas on a table with a decorative Chinese cloth, and two Oriental spears; all in allusion to the unprecedented overseas expansion of the young Dutch Republic. On account of the new discoveries, the field of geography also expanded on a major scale and by the 17th century the city of Antwerp had become an important centre of cartography. Exhibited in the same room is Gerard ter Borch’s Portrait of a Man Reading a Document (c. 1675), which features an atlas open at a page with a map of the Netherlands showing what some believe to be the Scheldt estuary and the city of Antwerp. Furthermore, in Room 25, The Naughty Drummer by Nicolaes Maes shows the interior of a middleclass house with a large map on the wall.

It has been suggested that this interior had some connection with the painter, as an inventory of his belongings recorded a considerable number of documents and books. The candle, almost a stub after many hours of study, could be an allusion to Van der Heyden’s work as an inventor, which he alternated with painting. Indeed, this artist was better known by his contemporaries for his innovations in street lighting and fire-fighting mechanisms, his greatest achievement in this respect being a system for pumping water for which he also wrote a manual.

Roelandt Savery

Mountain Landscape with a Castle

ROOM 23

Little is known about the early years as an artist of Roelandt Savery, a Flemish mannerist documented in Prague in 1604 as working for Rudolph II. The eccentric monarch commissioned from Savery a series of topographic illustrations of the Tyrol with mountain views, torrents, forests and other natural phenomena which are indirectly connected with this painting, as he based many of the works he later produced in his studio on the sketches and drawings he made on his travels.

It was precisely in the 17th century when landscape painting became a genre in its own right, as a result of the major transformation in society’s approach to nature, for it ceased to be regarded as inhospitable or menacing or a source of exploitation and instead became an inspiration for aesthetic appreciation. Furthermore, this occurred at a time when trade became the powerhouse of the European economy and obliged an ever greater number of people to do something hitherto unheard of in the West: travel.

One mid-century writer told of the origin of landscape painting through a fable: A gentleman and great art lover from Antwerp returned home from a long journey through the Liege and Ardennes Forest region. On his arrival in Antwerp he called on an old friend and local artist and found him sitting at his easel. To amuse his friend the traveller described the towns he had visited and the beautiful views, full of fanciful rock formations and imposing castles (like those in this picture) he had seen.

The painter (without the traveller realising) put his work aside and, taking up another panel, began to produce images of what his friend had described in such detail, thus immortalising his words. Later, as the loquacious traveller was taking his leave, he happened to glance at the panel and to his astonishment found himself looking at the landscape he had been describing, rendered as faithfully as if the painter had seen it with his own eyes.

Landscape painting is not a reflection or direct transcription of surroundings; it has much more to do with memory, description and, ultimately, travelling. By “reinventing” nature for us and showing us what we feel when we gaze on it, the artist teaches us how to see.

Frans Jansz. Post

View of the Ruins of Olinda, Brazil

Not on display

Post is famous as the first european artist to paint landscapes in the New World. With Albert Eckhout he became a member of an expedition led by John Maurice of Nassau-Siegen to the recently established Dutch colony of Pernambuco in northeast Brazil. Although the expedition focused mainly on trade and establishing an area in which the Dutch West India Company could operate safely, it was also intended as a scientific project to map territory and study Brazilian flora and fauna.

Although few paintings from Post’s time in the Americas have survived, on his return to Holland, and indeed until the end of his days, he reproduced from memory in his workshop a vast number of nostalgic variations of the places he had seen, filling them with exotic creatures, including the snake and bird seen here in the lower left-hand corner, and recombining elements as the fancy took him.

Willem van de Velde II

The Dutch Navy in Goeree

ROOM 28

After gaining independence from Spain in the 17th century, there began for Holland a period, known as The Golden Age, in which the Republic became the world’s greatest trading power. During those years Holland succeeded in expanding across the Indian and Atlantic oceans, superseding the Portuguese and Spanish. Luxury goods of all kinds reached its ports: spices such as cinnamon, saffron, peppercorns and cloves, Chinese porcelain, silk and Oriental carpets, to name but a few.

By 1650, around half of the merchant ships in the world were flying the Dutch flag. Established in 1602, the Dutch East India Company monopolised trade from the Cape of Good Hope to the Straits of Magellan. It was also empowered to declare war and sign peace treaties, build forts, seize foreign vessels and mint coins. In the words of one contemporary poet: “We explore the farthest reaches of the earth for love of profit.”

Willem van de Velde the Younger was one of the most outstanding 17th-century Dutch marine painters. For their oil paintings, the Van de Veldes (father and son) made sketches directly from nature and later reproduced the ships they had seen in full detail. They even sailed with the fleet to gain first-hand experience of navigation and naval warfare. It seems that the artist based this picture on a series of drawings executed in situ by his father which reproduced the ships so faithfully that it was later possible to identify them.

Willem Kalf

Still Life with a Chinese Bowl, Nautilus Cup and Other Objects

ROOM 21

This still life by Willem Kalf depicts a selection of luxury items connected with Dutch expansion overseas which, in contrast with still lifes of the domestic kind (like those by Van der Hamen on display in this room), reflect the “male” world of adventurers, trade and naval power.

The painting features commodities that symbolised social prestige: the wine glass with a filigree crystal cover, the Persian carpet from Herat, the nautilus set in silver-gilt and the Chinese Ming bowl decorated on the front with the eight Taoist immortals in relief.

With the Silk Road hitherto unknown objects began to appear in the West, as for example porcelain, brought to Europe by Italian merchants in the Middle Ages. The first European to describe the manufacturing process was Marco Polo, and it is possible that the word “porcelain” is due to confusion connected with the traveller’s story.

The term comes from porcella (“little pig”), the Italian word for cowrie, a mollusc whose highly appreciated shell was used as currency in some parts of the East. A cowrie is also featured in this room in Willem van Aelst’s Still Life with Fruit (1664). As the process for making exquisite china was a secret, some believed that it might be derived from the motherof- pearl shell of that highly appreciated mollusc.

Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié

In the Courtyard of the Customs-House

ROOM 24

During the enlightenment various factors came together to make the world a single system, one being the migrations of peoples (particularly through the slave trade) and another the appearance of new, interconnected markets on which consumer goods, ideas — and also diseases — circulated. Merchant fleets grew and international law attempted to shape and control these new interactions. New transcontinental empires sprang up, journeys of exploration began to receive financing, etc. Only against the backdrop of this world of constant exchange can the process of industrialisation which took place years later be understood.

This canvas, which has an extremely well documented history, was commissioned with the painter by Louis XV’s minister Abbot Terray (identified in the picture as the clergyman in black behind the man in the vermilion dress coat). When it was exhibited at the 1775 Salon, it received favourable criticism from Diderot, who added that the central figure in the green dress coat was the painter himself.

Johann Zoffany

Group Portrait of Sir Elijah and Lady Impey

Not on display

On discovering that “conversation pieces” — the genre which had made him popular — had become unfashionable, Johann Zoffany found himself forced to seek new patrons, and accordingly took a ship to India, arriving shortly before the date when this picture was painted. There he worked for the powerful British community, consisting of the civil servants, soldiers, merchants and adventurers who had settled on the subcontinent in the hope of starting a new life. Zoffany decided to bring his Oriental venture to an end in 1789 and finally sailed back to England.

The historian William Dalrymple states that on the way back Zoffany’s ship sank off the Andaman Islands. Lots were drawn to determine who was to feed the survivors, the loser being a young seaman who was promptly devoured — by Zoffany among others. The painter is regarded as the only member of the Royal Academy with a cannibalistic past.

This canvas features portraits of Sir Elijah and Lady Impey and their three children. The magistrate’s wife, who was a great lover of birds and exotic creatures (which she kept in a small zoo at her mansion), was also a keen patron of the arts. The illustrations she commissioned with Indian artists for her collection include the earliest known depictions of certain species of birds found on the subcontinent and are regarded by ornithologists as extremely valuable documentation. Indeed, the scientific community named a type of pheasant, the Himalayan or Impeyan monal (Lophophorus impejanus), now one of the national symbols of Nepal, in her honour.

Henry Lewis

Falls of Saint Anthony, Upper Mississippi

ROOM 31

In the mid-19th century a curious form of entertainment inspired by a fascination for the Far West and known as the “Mississippi Panorama” became fashionable in both the United States and Europe. It was created by a number of artists who painted scenes of the Mississippi on long scrolls and then travelled from town to town across America in wagons and boats, charging members of the public a modest fee to see a machine slowly unroll the scrolls and reveal the majestic panorama painted on them, while a narrator described the beauty of the scenes to musical accompaniment. The idea was to give the spectator the sensation of sailing down the river on a steamboat.

Of all these artists, the most talented and the one who made the longest panoramic view was Henry Lewis, who with his assistants painted a scene 365 cm high and approximately 404 meters long (the exact figures are unknown as none of the panoramas have survived). As Lewis’s panorama consisted of two parts — the Lower and Upper Mississippi — anyone who wished to see the complete view of the river had to attend two performances. After various preliminary studies, in the summer of 1848 (one year after this picture was painted) Lewis had taken a steamboat to Minneapolis, where he supervised the construction of a raft fixed to two canoes which he christened the Minnehaha.

In July and August of that year he and his companions had slowly descended the river, from the Falls of Saint Anthony to the town of Saint Louis, sketching riverside views as they went. Meanwhile, one of his assistants was capturing the river’s lower reaches. The panoramas were painted in Cincinnati and Lewis set out with his travelling show in the spring of 1849, working his way across the United States and Canada until 1851, when he sailed to Europe, to settle for the rest of his days in Dusseldorf. There he published Das Illustrierte Mississippithal, the story of his travels (with his own sketches), which is regarded as a jewel of American exploration literature.

The somewhat naive meticulousness with which the topography is depicted is reminiscent of the work of Lewis’s contemporary George Catlin. The close attention to detail can be seen in the Indian in front of the falls, for, despite the extremely small scale, the figure’s painted face, feathers and trinkets are clearly visible.

William Merritt Chase

A Girl in Japanese Gown. The Kimono

Not on display

In the mid-19th century, after a long period of almost total isolation, Japan began to receive merchant ships from other nations, thus opening its doors to the West. At the same time, ukiyoe prints (by masters such as Utamaro, Hokusai and Hiroshige), ceramics, fabrics, bronzes and enamels reached Europe and the Americas, quickly becoming enormously popular due to the vogue for japonisme.

Such works of art became a source of inspiration for many painters associated with Impressionism and interested in the Oriental perspective, flat areas of vibrant colours and freedom of composition that contrasted so sharply with Western norms and academic conventions.

The American painter William Merritt Chase travelled to Europe, where he came paintinto contact with the current taste for all things Eastern, and decided to become a collector of exotic objects — like the magnificent screen in this painting. When back in New York, Chase (who was well-known for his eccentric dress sense) moved into the old studio of Albert Bierstadt.

There, surrounded by stuffed birds, musical instruments and Eastern carpets, he would receive members of high society. An example of the Japanese influence mentioned above, A Girl in Japanese Gown is one of a series of portraits for which the subject was dressed in that traditional Japanese garment. Chase could not have been especially familiar with the strict Japanese dress code, however, since the right side of the girl’s kimono is folded over the left, in the manner customarily used for the dead.

Eugène Delacroix

Arab Rider

Not on display

In France in the course of the 18th century, the taste for the exotic gained ever more ground, with particular emphasis on the romantic aspects. Delacroix’s journey to north Africa proved to be a turning point in his career, for during that period he produced enough drawings and sketches to inspire compositions for the rest of his life.

Delacroix felt an overpowering attraction for things foreign, not only for their novelty but perhaps because it was when abroad that he had found what he regarded as his true nature. Like Socrates who, when asked where he came from replied that he was a citizen of the world, Flaubert, another traveller captivated by the East wrote: “I don’t give a damn for Normandy and la belle France ... I think I must have been transported by the winds to this land of mud. I must have been born somewhere else — I’ve always had memories or intuitions of fragrant shores and blue seas. I was born to be the emperor of Cochin-China, to smoke never-ending pipes, to have six thousand wives and fourteen hundred catamites, scimitars to cut off heads I don’t like the look of, Numidian horses, marble pools... My homeland is the country I love, that is the country that makes me dream, that makes me feel good. I’m just as Chinese as I am French.”

Travelling as a metaphor lies at the heart of Romanticism, a movement represented in the museum’s collection by Caspar David Friedrich, one of its greatest exponents. With its highly personal iconography his Easter Morning, also in this room, places us before a winding road whose symbolism appears to suggest life as a pilgrimage, while the figures on the shore in Fishing Boat by the Baltic Sea (c. 1830-35), from the Carmen Thyssen- Bornemisza Collection, fix their gaze on the dark immensity that stretches away before them.

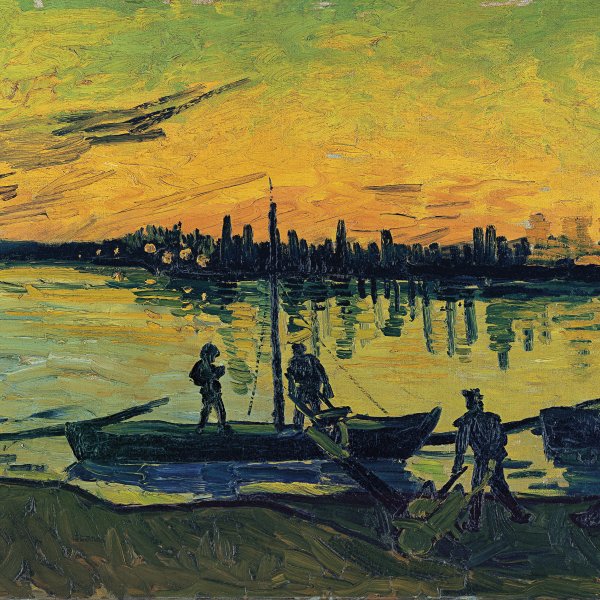

Vincent van Gogh

The Stevedores in Arles

ROOM 34

Vincent van Gogh arrived in Arles in February 1888 seeking the light-filled atmosphere of the French Midi. One of the reasons he gave to his brother Theo for moving there was that he wanted to capture the south in his painting- because of its affinity with Japanese landscapes - and and that he hoped through his work to help ensure that everyone would get to see it. This belief in the transformational power of art, in its capacity to hone our perceptual abilities and teach us to see more and better, recalls a remark by the British politician and writer Joseph Addison: “… we find the works of nature still more pleasant, the more they resemble those of art.” (1712).

In the powerful light of the south, Van Gogh adopted a palette of louder colours and a stylistic change with thick, elongated brushstrokes, sharp colour contrasts and silhouetting clearly indicative of the influence of Japanese art. “I saw a magnificent and strange effect this evening,” Vincent wrote to Theo at the beginning of August 1888. “A very big boat loaded with coal on the Rhone, moored to the quay. Seen from above it was all shining and wet from a shower; the water was yellowish-white and clouded pearl grey; the sky, lilac, with an orange streak in the west; the town, violet. On the boat small workmen in blue and white went back and forth, carrying the cargo ashore. It was pure Hokusai.”

Edward Hopper

Hotel Room

ROOM 45

There are many reasons why we feel impelled to go on journeys. But, as Baudelaire wrote:

... the real travellers are the ones who leave For leaving’s sake; Their hearts are light as balloons, They never turn away from their destiny And, without knowing why, always say, “Let’s go".

In his youth Edward Hopper spent some time in Paris. There he discovered Baudelaire, a writer whose poetry would accompany him for the rest of his life. Travelling is a recurrent theme in the painter’s oeuvre. Hopper once said: “To me the most important thing is the sense of going on. You know how beautiful things are when you’re travelling.”

In 1925 Hopper bought his first car (a Dodge) and drove down from New York to New Mexico. From then on he never stopped roaming America with his wife Jo and capturing those desolate landscapes of his, making no concessions to picturesqueness or exoticism: service stations, empty parking lots, waiting rooms, neon-lit highway diners, hotel rooms with solitary, introspective, waiting figures, Thanks to the cinematographic quality of his paintings, we can imagine, as if in a road movie, stories of wanderers and the dispossessed setting out on adventures, fleeing boredom, bad luck or abandonment.

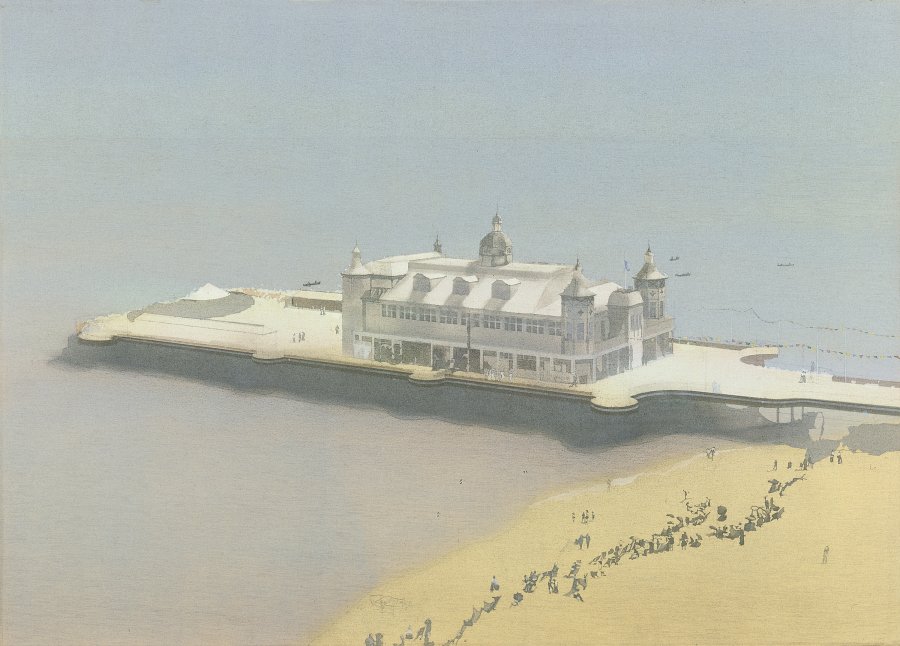

Michael Andrews

Lights V. The Pier Pavilion

Not on display

This picture belongs to the lights series, which consists of seven large canvases embodying the painter’s spiritual transformation through the Zen notion of liberation. The title is a reference to the symbolist poet Rimbaud’s Illuminations and evokes that same state of awareness: a view of the world stripped of any distortion imposed by subjectivity. As the artist himself explained: “It is to do with getting rid of the ideas we have of ourselves. Of what we call the ego.”

The series covers a journey in a balloon which the artist used as a symbol of the “skin-encapsulated ego”, an expression inspired by the writings of the psychologist R.D. Laing. Andrews painted the solitary progression of that balloon over empty landscapes, urban vistas and coastal spas as a symbol of the soul’s odyssey in search of liberation, finally reaching the calm waters of a beach (the chosen landing site) after overcoming obsessive attachment to the ego.

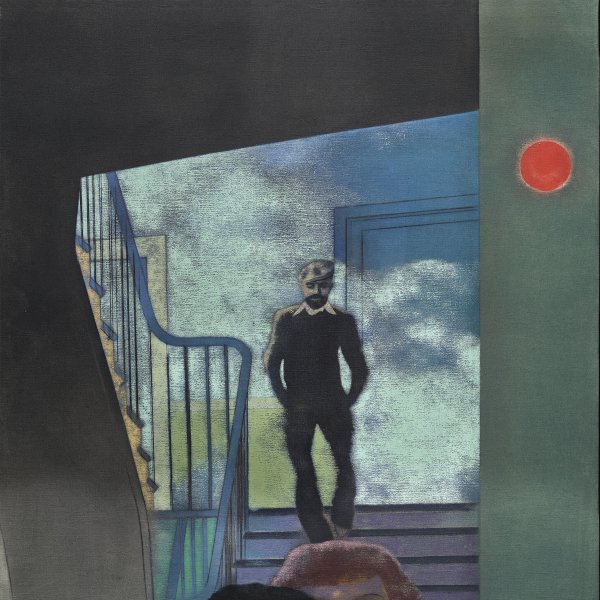

Ronald B. Kitaj

Smyrna Greek (Nikos)

ROOM 52

“I like the idea that it might be possible to invent a figure, a character, in a picture the way novelists have been able to do,” Kitaj once confessed. The literary roots of his painting are particularly evident in Smyrna Greek (Nikos), not only because the figures are two poets, but because the scene tells a story.

The artist gave a brief explanation of this painting in the catalogue of his exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London in 1994: “This portrait of my friend Nikos Stangos was inspired by his fellow Greek poet Cavafy, who described his daily walk past the brothels in the port of Alexandria. I had just returned to London from my only trip to Greece, which lasted very few days, and while he posed for me in that walking position, I told Nikos about my bizarre and unconsummated wandering down the port of Piraeus, as if in imitation of C.P. Cavafy. So the painting is about the two poets and me.”

A great voice in 20th-century poetry, Cavafy wrote one of the most famous poems about journeys, Ithaca, which draws a parallel between Odysseus’ travels and life, viewed as an adventure, in which the destination is not as important as our experiences along the way.

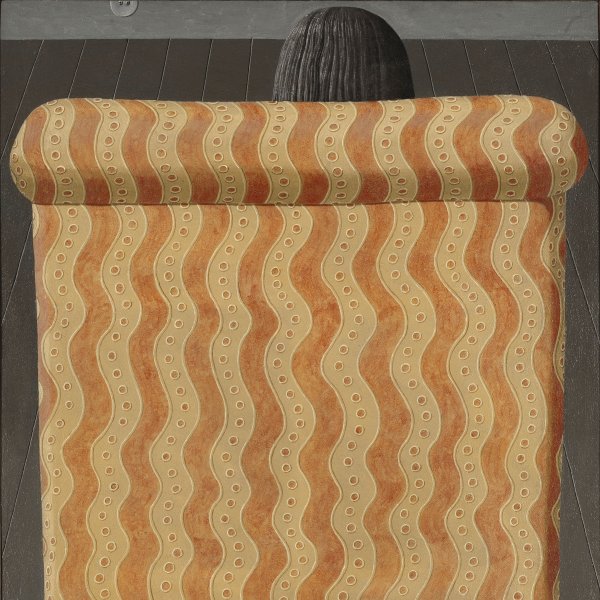

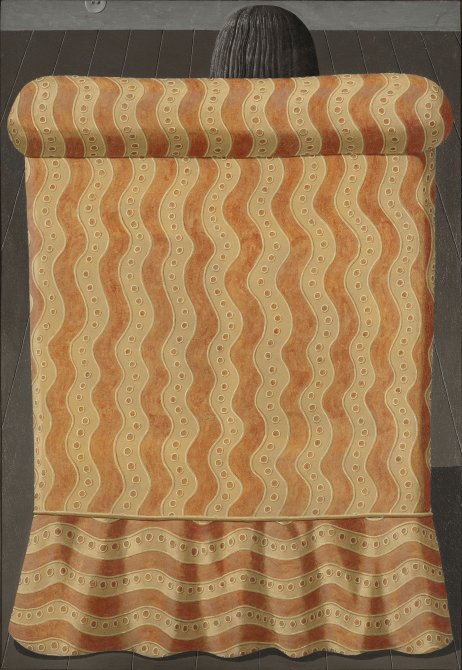

Domenico Gnoli

Armchair No. 2

ROOM 52

Pascal declared: “the sole cause of man’s unhappiness is that he does not know how to stay quietly in his room.”

In the late 18th century, a young French soldier, writer and painter called Xavier de Maistre made an imaginary journey around his room. Partly autobiographical, his book A Journey Around My Room (Voyage auteur de ma chambre) tells of how an officer, obliged to remain in confinement for a long period, describes his thoughts and the limited space around him as if it were a foreign country.

De Maistre was deeply fascinated by hot-air balloons, whose invention was attributed to the Montgolfier brothers. These had gained international fame through their tests at Versailles in the presence of Louis XVI in which they sent a basket aloft hooked to the balloon and containing three docile passengers — a sheep dubbed Montauciel (which may be translated as “ascends to the sky”), a duck and a cockerel — to study the effects of the air at high altitude. With help from a friend, De Maistre — inspired perhaps by Leonardo da Vinci — made himself some wings with wire and paper while dreaming of an impossible journey to the Americas.

Two years later he managed to secure a place in a hot-air balloon and for a brief period flew over Chambéry before crashlanding in a nearby forest. There are various ways of travelling, and one — highly recommended for those without the financial wherewithal or who are afraid of heights or abhor mass tourism — is without luggage. Or else, as De Maistre suggested, sporting comfortable cotton pyjamas. The satisfaction we derive from the journey may depend more on our attitude than our destination or our sensitivity towards the beauty of the small things that surround us.

Let us bring this thematic tour to an end with a quote from Gnoli, the creator of this Armchair, painted in Majorca in summer 1967: “I always use elements which are given and simple; I never want to add anything or to eliminate. I have never any desire to deform; I isolate and I represent. My themes come from the present, from familiar situations, from daily life. Because I never intervene actively against the object, I feel the magic of its presence.”