By Teresa de la Vega

The body is “good for thinking”. Our consciousness of ourselves as corporeal creatures is at the very core of the human identity. But the body isn’t just a biological entity. It’s a social construct as well, the place where the strategies that govern power and the gender stereotypes that have shaped western culture converge.

The nude hovers between organic reality and social mask, between what biology has “given” and what culture has “added”. Since it is free from specific temporal markers, we might think that it has a universal, eternal value. But the truth is that artists who have depicted nudes have imbued them with the zeitgeist of their time, with their aesthetic inclinations and the changing senses of morality.

The nude as a symbolic form has aroused countless and often contradictory sentiments and ideas: innocence or sin, harmony or pathos, truth or confusion, communion with nature or social alienation. The body has been conceived as a sanctuary and a prison, as a matter of pride and a scourge, and above all as an object of desire, but there is no doubt that the contemplation of a beautiful naked body provokes an erotic response, or at least suggests that possibility.

Although it has been a recurring motif in art throughout the ages, from the Palaeolithic to the present day, it is only western culture that has prompted the idea of offering the body, in itself, as an object of privileged contemplation, treating it as an artistic genre in its own right, subject to specific rules or conventions, somewhere between realism and idealisation.

But what is the nude? The British historian Kenneth Clark describes it as “an art form invented by the Greeks in the fifth century BC, just as opera is an art form invented in seventeenth-century Italy”. Clark’s succinct defi-nition suggests that the nude is not merely a theme of art but a form of art.

The title of Clark’s book’, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, leaves no doubt as to the author’s point of view: he makes a distinction between the nude and nudity, emphasising that the nude is not simply the direct transcription of an unclothed body but rather—as a symbolic form and ideal conception—a body “clothed in culture”. Hence, nudity of the body is the condition of being naked, of not wearing any clothes, whereas the images conveyed in the western artistic tradition represent balanced bodies, full of confidence, re-formed bodies.

Tour artworks

Auguste Rodin

The Birth of Venus (The Aurore)

ROOM B

This route begins with one of the sculptures that was commissioned directly from the artist by August Thyssen, the grandfather of Baron Hans Heinrich Thyssen, in 1905. Rodin was the last of the great Romantics; his demise coincided with the demise of an entire age. No other artist of the 19th century managed to infuse the nude with the sheer expressiveness that Rodin achieved, reinstating sculpture to the lofty status it appeared to have lost. Rodin looked to the past, to Michelangelo, although like Degas he was well aware of the lifelessness of the excessively contrived academic nude. He would walk around the models in his studio, making sketches and encouraging them to move about, to play or dance, to unconsciously adopt different postures. “I have unbounded admiration for the nude. I worship it like a god”, he declared. But his goal was not so much the nude in itself but capturing the specific weight of the bodies, how those bodies occupied space and caught the light. Rodin developed the same profound familiarity with the human body that the ancient Greeks acquired at the palaestra.

According to the Theogony of Hesiod, the goddess of beauty was born in her resplendent nakedness in the foam of the sea fertilised by her father Uranus, opposite the coast of Cyprus. Through one of the guests at the Symposium, Plato asserted that there were two Aphrodites, which he called Celestial and Vulgar. Venus Coelestis and Venus Naturalis, as they would eventually come to be known, became emblems of spiritual love and carnal passion, respectively.

In ancient Greece the nude was glorified as the ideal form. As early as the seventh century BC, the human figure became the central theme of artistic depictions. However, although western tradition has granted greater prominence to the female nude, that was not the case originally. Depictions of nudes were initially reserved exclusively for the figures of young men or kuroi that were erected on top of graves. Female nudes were absent from Hellas in the sixth century BC, and in fact they were still rare in the fifth century BC. This taboo about the nudity of female deities, as opposed to the case with male gods, inspired numerous legends about the punishments that were meted out to humans like Tiresias and Actaeon for daring to gaze upon the sublime body of a goddess.

Moreover, after the second century AD the nude practically disappeared, save for rare exceptions, until Neo-Platonic speculations revived it in the Renaissance. Once an object of physical desire, the body became a model of spiritual excellence. And thus was Venus reinstated and rescued from her medieval disgrace.

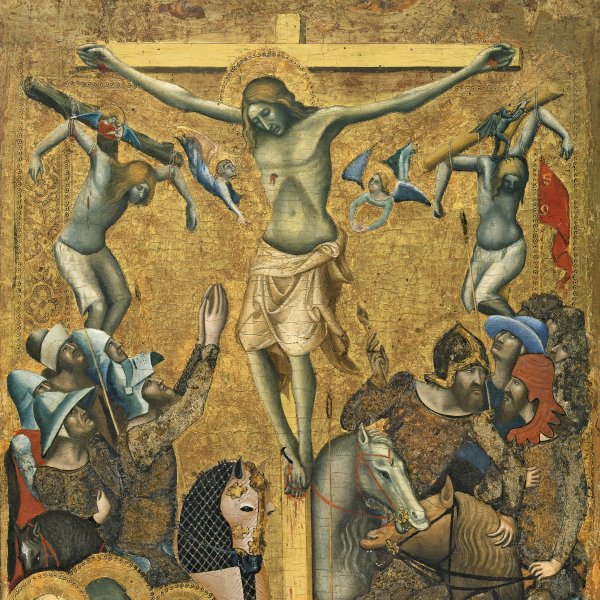

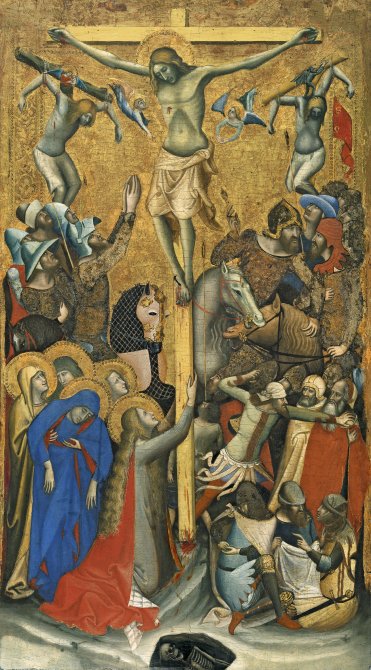

Vitale da Bologna

The Crucifixion

ROOM 1

During the Trecento new trends emerged that would eventually culminate in the Renaissance. Although Vitale da Bologna placed his figures against a gold background, more in keeping with the medieval tradition, he attempted to create a convincing sense of space and lend coherence to the two groups of figures that flank the cross. The solution proposed to identify the two thieves is of particular note: a little demon carries off the bad thief’s soul and angel does the same for the good thief.

As the philosopher Julia Kristeva says, the “Christian miracle” lies in the “negotiation that occurs between the invisible truth of the Bible and the Greek worship of appearance”. Meanwhile, in the Ten Commandments that Moses received it states: “You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not worship them or serve them.” This categorical rejection of idol worship may seem unequivocal, but it was certainly not the case.

The tension between the aniconical rejection of images that is found in Judaism and the predominance of the visible appearance in the classical world—the theoria of the Greeks—eventually culminated in the definitive conversion of Christianity into a figurative religion. At the same time, during the centuries that unfolded between Palaeo-Christian art and humanism, the centrality that the worship of the human nude had occupied in the Greek world gave way to the concealment of the flesh.

As Saint John Chrysostom claimed, “The well-shaped body is merely a whitened sepulchre, the parts of which are full of so much uncleanliness.” Its depiction was only permitted in the sacred context, for illustrative purposes and provided that it was essential for understanding the Christian message. For example, scenes like the discovery of nudity by Adam and Eve, which marked their distance from God, the Crucifixion, the resurrection of the flesh and the suffering of saints escaped ecclesiastical reprobation.

Nevertheless, over time, and in spite of the Christian horror of nudity, the naked figure of Christ was finally accepted as the canon in depictions of the Crucifixion. The early images of this key event in Christianity were of two types: those that showed the crucified Christ naked but for a perizoma or loincloth, and those that presented him in a tunic or colobium. Both types are rare in Palaeo-Christian iconography and none pre-date the fifth century, partly because the Church thought that inspiring depictions of the resurrection or miracles would gain more followers. Besides, Christ hardly ever showed any signs of suffering.

Pathos was introduced little by little, expressed through movement—the curved emaciated body, the bent knees— so that by the ninth century the rigid garments had fallen into disuse and been replaced by the light cloth with which, according to the popular medieval text Pseudo-Bonaventure Meditaciones Vite Christi, Mary covered her son. This device enabled the Church to emphasise the human nature of Christ.

Medieval theology made a distinction between several types of nudity: the nuditas naturalis of the newborn, the image of purity not yet contaminated by sin, like Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden before the fall; nuditas temporalis, an involuntary situation caused, for example, by poverty; nuditas criminalis, provoked by the sexual appetite that entails condemnation of the soul, as found in those of a dissolute nature; nuditas virtualis, a nudity born of the decision to lead a life of renunciation, as exemplified by John the Baptist; and finally, nuda veritas, or the nudity of Christ on the cross.

In Roman law, crucifixion was the “supplicium servile”, reserved for slaves, low-class citizens, foreigners and criminals of all types, social outcasts who were stripped of their clothes to undergo capital punishment. In offering himself up for contemplation in all his vulnerability, Jesus was as naked as the criminal and slave, but precisely because of that he stood triumphant, armed with the nuda veritas, the revelation of salvation.

While the bodies of the thieves on both sides are contorted and twisted in pain, Christ’s body—like the early Greek nudes—obeys the canon that satisfies what Kenneth Clark calls the interior ideal. With the Crucifixion, nudity was no longer the consciousness of mortality; rather, it announced a possible salvation, because by that time Christian art had understood it could depict the body not only as a prison for the spirit but as the image and likeness of the divine in the mortal world.

Lucas Cranach the Elder

The Nymph at the Fountain

ROOM 9

The nudes created by Masaccio and Donatello at the dawn of the Renaissance would become some of the most significant works in the history of art. The human figure recovered its centrality, as the measure of all things and a favourite subject of philosophical speculation and artistic representation. Later on, the Mannerist period witnessed the triumph of the body in itself, while in the Quattrocento the certainties of humanism, which upheld nudity as the most complete expression of perfection, gradually gave way to a multiple vision. Non-naturalistic torsions of the body abounded and there was a progressive eroticisation of the subject, which became more sensual (as visitors may have seen in Bronzino’s Saint Sebastian in the previous room). A similar level of sophistication is found in the creations of Cranach and Baldung Grien, both of whom contributed to the triumph of the Mannerist nude in northern Europe.

Cranach, one of the great German painters of the Renaissance, developed a highly personal version of the nude when he was in his sixties; the series of beauties to which this nymph belongs date from after 1530. This painting depicts the nymph of the Castalian Spring, whose waters philosophers and poets imbibed in search of inspiration. The quiver and bow may be references to Diana or Cupid, while the two partridges allude to sensuality.

The nymph’s posture recalls the famous Venus of Dresden and certain models used by Titian. However, Cranach eschewed the Italian influence and created a strictly German prototype of icy sensuality, a female canon of elongated forms, broad forehead, almond-shaped eyes, narrow shoulders, small breasts, long legs and a slightly rounded belly.

The nymph’s figure exudes a certain “Gothicism” in which stylisation takes precedence over anatomical accuracy. To appreciate the extent to which Cranach managed to imbue the Gothic body with a new style, it is interesting to compare this work with another one in the next room: Adam and Eve by Gossaert, an artist who went to great pains to create a synthesis between the Italian nude and the influence of Dürer’s work on his painting.

In the west, women have been regarded as the “fairer sex” since the Middle Ages and have been virtually the sole protagonists of nude images. The reclining figure of a woman, the dominant model since the Renaissance, was uncommon in classical antiquity, although it occasionally adorned the corners of Bacchic sarcophagi. In fact, in non-European traditions—i.e. Indian, African, Chinese and Pre-Hispanic—figures are rarely depicted in the supine position. And where the theme of a work is sexual union, the woman is usually represented as just as active as the man.

The invention of the classical nude is attributed to the Venetian painter Giorgione. The Venus of Dresden, the prototype of all Renaissance and modern Venuses, received such acclaim that for four hundred years it inspired the nudes of the greatest painters (Titian, Rubens, Courbet, Ingres, Manet, Renoir and even Cranach, as we see in this work), who created endless variations on the same theme. The nymph’s eyes are closed (“I am the nymph of the fountain,” reads the label in the top corner. “Do not disturb my sleep, I am resting”), and her sleeping status seems to insinuate passivity and vulnerability. She is immersed in her own world, but in spite of this strategy to avoid the spectator’s gaze, she is well aware that she is looked upon; she establishes a seductive complicity with the spectator, offering up her femininity for examination and unbridled enjoyment of her beauty.

In fact, it would be true to say that in the western pictorial tradition of the nude, the true protagonist of the picture is the (predominantly male) spectator. It is through him that the figures embrace their nudity. Nevertheless, the spectator is a stranger still wearing clothes, so the relationship established is based on the unequal footing that is so firmly rooted in our culture.

All of this helps us to appreciate the difference in the European tradition between nudity and the nude as an art form. A nude is not only the starting point of a picture; it is a mode of seeing, subjected to certain conventions.

For a naked body to become “a nude”, it requires others to view it as an object. Nudity is revealed for what it is, whereas a nude is exhibited.

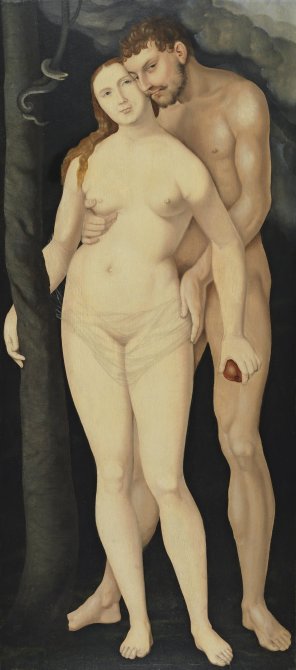

Hans Baldung Grien

Adam and Eve

ROOM 9

The first woman, eve, was also the first woman who appeared naked in Christian iconography. Nothing speaks to us of nature and the human condition more eloquently than a simple naked body. Thus were our first ancestors in the Garden of Eden, in a state of primeval innocence that was lost forever as a consequence of sin. From the moment Adam and Eve became aware of their nudity, a dialectic emerged between that nudity and the modesty that impregnates western culture.

In Genesis we read: “When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it. Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they realised they were naked; so they sewed fig leaves together and made coverings for themselves,” (Gn 3: 6-7). As the Biblical story highlights, we might say that nudity is engendered in the spectator’s mind and revealed in their consciousness, which is a state of the act of gazing.

This act of gazing was equated with sin, and knowledge with sexuality, because the body was no longer a reflection of divine perfection but a cause for shame. Several factors converged in this rejection by the early Christians, including the Platonic theory that spiritual beings are degraded when they acquire corporeal form, coupled with the Judaist anaconic tradition that opposed images. Pagon idols were said to be the dwelling place of cunning demons who had taken on a pleasing appearance to deceive the faithful, so nudity acquired a diabolic connotation (see, for example, the work of Jan Wellens de Cock, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, in Room 9, in which naked women lie in wait for the virtuous male).

During the Renaissance, the nude became an increasingly secular motif, finally acquiring the status of a an object of aesthetic appreciation in itself. Consequently, Eve was no longer the personification of shame and repentance but a sensual provocateuse, while the rejection that the body had suffered as a result of Christian morality merely served to accentuate its eroticism, as is plain to see in this work.

In Adam and Eve, Grien presents us with a magnificent study of the male and female bodies. Considered to be Dürer’s main disciple and closest collaborator, the artist developed a highly characteristic and expressive style that was far removed from his mentor’s Renaissance restraint and composure. When we compare this work with the one on the same theme by Dürer, on display at the Prado Museum, Baldung’s originality and the distance between the two artists are immediately evident.

Eve, in the foreground, covers her nudity not with fig leaves but with a transparent veil that seems designed to emphasise rather than conceal her pubis, for she knows that she will be even more alluring if she preserves a certain mystery, however minimal. Her right arm is draped around the Tree of Paradise, while her left hand holds the apple, the only note of colour in an otherwise somewhat monochrome work. Adam emerges behind her, resting one hand on her hip and caressing her breast with the other. Eve, impassive, abandons herself to the possessive embrace and looks into the middle distance, although she is well aware of the spectator’s gaze. Adam looks at us provocatively: shame has become a type of calculated exhibitionism.

Giambattista Tiepolo

The Death of Hyacinthus

ROOM 17

In the greek myth, Hyacinthus was a beautiful youth and lover of the god Apollo. As they played at throwing the discus, the god of the wind, jealous Zephyrus bent on killing the youth, blew the discus off course. In this painting the discus has been replaced with the racquet and balls used in pallacorda, the forerunner of tennis.

From the victim’s blood sprouted a flower, which has been identified with the knight’s spur or the iris, rather than with the plant we now call the hyacinth. A metaphor for death and the rebirth of nature, the plant contains the promise of resurrection, although the fate that befell Hyacinthus is also open to interpretation as an allegory of pederasty in the Greek world because this institutionalised practice dictated that the relationship must end when the young lover reached maturity.

Tiepolo, a leading figure in the glorious dying days of triumphant Baroque painting, recreated the scene in what has been described as an operatic setting. Bathed in a diffuse light, the figures make declamatory gestures under the mocking gaze of the statue of a satyr.

However, tastes were changing when this work was painted. The turning point that occurred in the art world during the mid-18th century was driven, among other things, by the texts of Johann Joachim Winckelmann. The nude was reinstated as a central theme thanks to the recovery of the classical aesthetic ideal, while the exaggerated naturalism of the Baroque artists paved the way to a refined idealisation rooted in Graeco-Roman prototypes. Precisely one year after the completion of this work, Benedict XIV founded the Academy of the Nude in Rome. A branch of the Academy of Saint Luke, it encouraged drawing from life, although it was not until the following century that professional female models began to emerge. Until then, artists had to use male models or studio apprentices and then adapt their anatomy, with which they were more familiar, to the female anatomy.

The proud exhibition of the nude body was born in classical Greece in a clearly defined context: the gymnasium (from gymnos, meaning nudity). This was the place where young men trained (not so young women who, except for in Sparta, remained in the gynaeceum), while the palaestra and competitive sports were the scenes where pederasty—that is, the physical and emotional relationship between an adult, the lover or erastes, and a youth, the beloved or eromenos— took place.

In his Reflections on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755), Winckelmann states:

"These exercises gave the bodies of the Greeks that great and manly contour which the Greek masters imparted to their statues, with no vague outlines or superfluous accretions [...]. All the precepts and injunctions on the cultivation of the body from birth to adulthood, and on its preservation, nurture and embellishment by natural and artificial means, were designed to enhance the natural beauty of the ancient Greeks; they justify us in asserting, with the highest degree of probability, that the outstanding physical beauty of the Greeks far surpassed our own."

This famous passage clearly expresses the idealisation of Greek art, a process that had begun in the Renaissance. Winckelmann concludes: “The schools of art were the gymnasiums, where the young people—though modestly required to wear clothes in public—performed their exercises completely naked.”

Indeed, the first images of nudes were all male, created to celebrate the beauty, physical strength and virtue that were considered to be the prerogative of the aristocracy. The ideal of the kalokagathia, the fusion of noble appearance and moral excellence, enabled a free man to imitate Apollo himself, to the extent where the adjective “Apollonian” came to signify a harmonious manly body.

Carlo Saraceni

Venus and Mars

ROOM A

The extraordinary glorification of the nude that took place during the Renaissance continued until the Council of Trent (1545-1563). A few years later a seminal text was published: the Discourse on Sacred and Profane Images (1582) by Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, well-known for his zeal. His work set out the iconographical rules and principles that artists of the Counter-Reformation were to follow, in keeping with the new demands of worship:

"The demon attempts to divert the true and proper use of images into other twisted and illicit channels, so he causes a painter to make an Apollo instead of a Christ, and a sculptor to compose a fabulous transformation instead of the statue of a martyr. He sees to it that figures are painted nude for the most part and very lasciviously. He even treats the saints this way, and if the blessed Mary Magdalen, or Saint John the Evangelist, or an angel, is depicted, he makes sure they are adorned and decked out worse than trollops or actors."

And he concludes:

"Please God, let a host of iconoclasts arise— holy iconoclasts, who will decry the dishonest and abusive images that are now being introduced every day, just as the iconoclasts of old once ungratefully and wickedly decried holy figures. And may it please God that Christian painters and sculptors see the error of their ways and return their arts to the purity through which they were introduced."

Meanwhile, Cardinal Federico Borromeo wrote in his De Pictura Sacra (1624):

"I have never clearly understood how painters could justify their images of naked men and women, for they never appear in this guise in streets or public squares, and seeing them thus is a cause for shame and affront... Artists commit this same error when they depict the infant Jesus breastfeeding, leaving the chest and neck of the Mother of God uncovered and on view, when they should be depicted with the utmost care and modesty. Many artists also show the naked legs of the saints, both female and male; worse still, they depict them so close together that they could arouse evil thoughts in the spectator... How is it possible that the progeny of the Catholic Church, the disciples of the Saviour, should wish to gaze upon naked Cupids and Venuses?"

According to Borromeo, it was not only the Church but the representatives of the civil government that should intervene “to eradicate such filth from society by force”.

Many things have changed since then... Not long after the close of the Council of Trent, Danielle da Volterra, Il Braghetonne, was commissioned to undertake a controversial task: covering the risqué nudes in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement. But in 1524 a new scandal broke out following the publication of the Modi, a series of sixteen engravings of sexual positions illustrated by Guilio Romano (this museum owns two of the artist’s drawings, A Satyr and A Female Satyr, not on permanent display due to the conservation conditions required for works on paper) and accompanied by Pietro Aretino’s sonnets. The artist fled to Mantua to escape the wrath of Pope Clement VII, who had to content himself with imprisoning the engraver, Marcantonio Raimondi.

In spite of the change of direction imposed by the Counter-Reformation and the prison sentences provoked by the new sensibility, certain images that aroused desire were deemed appropriate and legitimate, provided that they were exhibited in the privacy of aristocratic mansions and had a symbolic or mythological pretext.

This work by Saraceni belongs to this very specific category of private pictures with an explicit erotic theme and strong voyeuristic component. It depicts Venus, the wife of Vulcan, in the company of Mars, with whom she had an affair, as recorded in numerous classical sources from the Homeric poems to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The lovers romp on the bed in the presence of frolicking putti, while one of them plays irreverently with the god’s armour, for the imposition of force has little do in the face of passion.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the doctor and writer Giulio Mancini, one of Caravaggio’s first biographers, wrote: “Similar lascivious images are appropriate for the place to which husband and wife retire since the sight of these paintings would encourage sexual excitement and the birth of beautiful, healthy, and strong sons.”

Eugène Delacroix

The Duke of Orleans showing his Lover

ROOM 29

In the 19th century there was a significant change in the way that spectators looked at art. The new affluent audiences expected more immediate gratification from the artwork, an appreciation that did not necessarily bear any relation to their literary knowledge or religious beliefs. They demanded entertainment; they wanted to be diverted.

After the extraordinary precedent of Goya’s Naked Maja, the 19th-century zeitgeist was ready to embrace the nudes of Delacroix and Géricault (this museum owns a magnificent work on paper by the latter, The Kiss, which is occasionally exhibited in this room). Realists and Romantics strived to create a “living art” based on the formula used by Courbet, as opposed to the sterility of academic art.

In an increasingly complex socio-cultural scenario, the nude was acquiring new and often contradictory implications, on a scale that ranged from a frankly raunchy eroticism to the “artistic nude”, designed—supposedly—for mere aesthetic delight. Either it was rejected as an offence against public morality, or was deemed acceptable because it belonged to the realm of fine arts and to a genre based on prestigious ancient models.

Besides, women had begun to claim a more prominent role in society and the world of work, while colonialism had prompted a taste for the exotic and for Orientalist painting, of which Delacroix was an illustrious exponent. This gave rise to a very popular pictorial sub-genre characterised by odalisques reclining on soft cushions, captive slaves and young ladies surprised at their toilette.

The Romantics of the 19th century also looked to the past for inspiration, undoubtedly as a nostalgic reaction to the rapid social changes which the industrial revolution had brought about, leading to the disappearance of traditional ways of life.

It is to this fascinating world of fiction that the scene on this canvas belongs, which in turn recalls a famous passage by Herodotus on the imprudence of Candaules, king of Lydia. Legend has it that the Duke of Orleans had an affair with Mariette d’Enghien, the wife of his former chamberlain, Aubert le Flamenc, and exhibited her naked to the latter, save for a sheet draped across her face. As the story goes, the unfortunate husband failed to recognise the familiar body of his wife. Interestingly, Delacroix partly reveals the face of the duke’s paramour in the halflight, thus implicating the spectator in the deception, who takes on the role of an imaginary lover casting our gaze over the woman’s body.

The moral code of the 19th century was riddled with incoherences and prudery: the museums were full of pictures and statues of nude women, yet simply showing an ankle was deemed to be the height of immodesty. Between 1827 and 1838, access was restricted to the exhibition halls of the Prado Museum where nudes were on display, and years later, in the 1870s, visitors to the Salon des Refusés were outraged by Manet’s pictures Luncheon on the Grass and Olympia, both of which showed nude bodies without any religious or mythological pretext. This marked a key turning point in that artists began to question tradition, and the principles of the academic nude as the ideal of beauty collapsed. From that point on, the nude became a subject for formal experimentation and a battlefield for aesthetic and expressive provocations.

Meanwhile, the simultaneous development of photography kindled the debate on the relationship between reproduction and creativity. A lively trade emerged in nudes and catalogues of models, often anonymous, which served as inspiration and were avidly collected by numerous artists, including Delacroix. This proliferation democratised artistic images, which had previously been reserved for the eyes of collectors or those who visited museums and exhibitions.

In these early photographs, which often had an erotic tone, the models were captured as if they had been surprised in an intimate setting, immersed in dreamy gestures or pampering themselves in the bath. However, as time went by they adopted a greater insolence, conveying the impression that they knew they were being observed. Gone were the veiled gaze and false modesty of the demure Venuses.

Otto Mueller

Two Female Nudes in a Landscape

ROOM 36

Before contemplating Müller’s work, visitors may have noticed a painting in a previous room, Pablo Picasso’s Study for the Head of “Nude with Drapery”, which he painted in the summer of 1907.

That same year he also produced Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, widely considered to be the cornerstone of modernity since it marked a radical break with the tradition that had preceded it. His figures adopt poses borrowed from the ancient classical repertoire, but their anatomy is treated in the concise form associated with extra- European arts, black art and Iberian sculpture, in complete opposition to Academicism.

Although it may seem deliberate that the female nude is the prominent motif of two ultra-revolutionary works, Manet’s Olympia and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the theme is actually irrelevant. What matters is their radical plastic conception, the discovery of a new language. The avant- garde movements abandoned the quest for likeness; they fragmented the body and splintered the face, although they continued to call it a “nude” or “portrait”, even if there was no intention whatsoever for such pictures to be defined by their imitation of the model. As Picasso said:

"I want to say a nude. I don’t want to make a nude like a nude. I only want to say breast, say foot, say hand, belly. If I can find a way to say it, that’s enough. I don’t want to paint the nude from head to foot, but just to be capable of saying that. That’s what I want. When we talk about this, a single word is sufficient. Here, the nude says what it is with simply a gaze, without a word."

It is probably true to say that at the end of the 19th century, sexuality, definitively dissociated from reproduction, was “rediscovered”. Berlin witnessed the beginnings of its scientific study with the birth of sexology and Vienna saw the advent of psychoanalysis. Although there were precedents, the radical exploration of the body and eroticism by these artists forced the limits of what was considered to be morally acceptable. The representatives of the avant-garde were determined to eradicate the bourgeois connection between sexuality and propriety. They wanted to shake off all moral constraints and the shameful concealment of the body to reveal the naked truth and the power of desire.

Otto Müller joined the Expressionist group Die Brücke [The Bridge] in 1910 and immediately embraced its conception of life and art. A little earlier, his fellow members Kirchner, Pechstein and Heckel had discovered Dangast on the North Sea and the Moritzburg lakes near Dresden, which they frequented with their models and girlfriends to realise their dream of living life free from social coercions, openly challenging the hypocrisy of their time. As Müller said, his main desire was to express his yearning for harmony with nature through these angular female bodies inspired by ancient Egypt.

Müller’s sensual, luminous bathers convey the same Arcadian joy of life as Kirchner’s painting Curving Bay. However, they lack the latent belligerence of the latter’s prostitutes (like the one we see in Street with Red Streetwalker) and of Schiele’s explicit Nude Girl with Arms Outstretched, both on display in nearby rooms. But if we compare them with Manguin’s The Prints, it is perhaps possible to perceive a difference between French art and the Austrian and German avant-garde. In the latter case, the individual appears to be reduced to an existential nudity. The expressive focus is often centred on the subject’s corporeal identity, on the possibility that the controversial treatment, be it thematic or stylistic, could become an attack on the rules of decorum. And, in a wider sense, the focus is on the opportunity to explore the deepest implications of sexuality or to reflect on the artist’s radical antagonism to society.

Henri Manguin

The Prints

ROOM H

The new debate surrounding nudity comprised two positions: the conception of the nude as a pretext for purely formal reflection, and nudity as a metaphor for a break with convention and as the expression of a desire for transgression.

While Gemano-Austrian art was transfigured by a painful awakening, French artistic production was dominated, at least up to a point, by a desire to reinstate the nude in the history of a genre which, while certainly not without its problems, called for the reformulation of its limits. This redefinition of the gaze, a type of visual plenitude, is what characterises the Fauves. “What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject-matter [...] a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue,” said Matisse, the author of sensual works like Luxury, Calm and Pleasures (1904), Joy of Life (1905) and The Dance (1909).

The Prints is undoubtedly one of the most complex works produced by Manguin. The two figures represent the same model: Jeanne, the artist’s wife, dressed and naked, facing one another. Since they are the same woman, the scene could be interpreted as the resolution of the conflict between model and wife, studio and home, or even artistic creation and daily life.

The nude in The Prints is clearly based on the woman with the zither viewed from behind in the foreground of The Turkish Bath by Ingres, which in turn is the transposition of an archetype formulated in the famous Valpinçon Bather by the same artist, currently on display at the Louvre Museum.

With respect to the contrast between dressed and undressed, a few years earlier the Manual del pintor de historia by Francisco de Mendoza, quoted by Carlos Reyero in Desvestidas. El cuerpo y la forma real, asserted: “In women, any naked part is pleasing to the eye; but it should be known that artfully concealing certain parts increases their beauty and grace.” The back view allows the spectator to revel in the contemplation of the sensuous curves of the woman, who seems unaware that she is observed.

The model appears distracted, leafing through the prints that her alter ego shows her, oblivious to the artist’s activity and the gaze of the spectator, who seems to caress the canvas thanks to the tactile qualities evoked by the extravagant colours of the drapery in contrast to the smooth white skin, for artistic creation may also be conceived as an act of love.

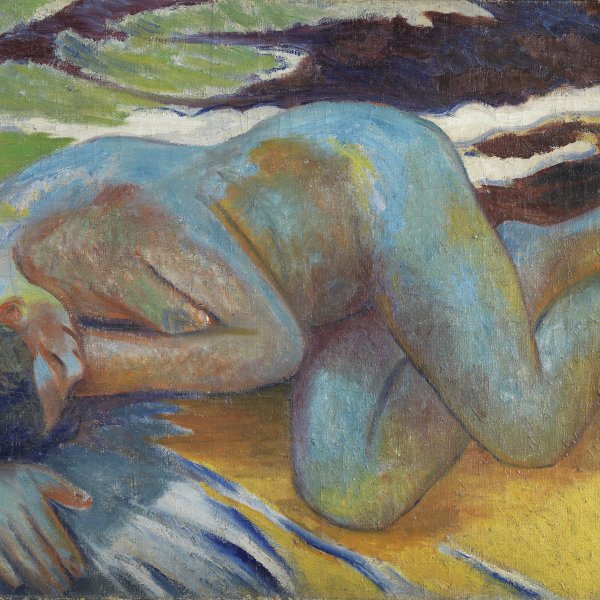

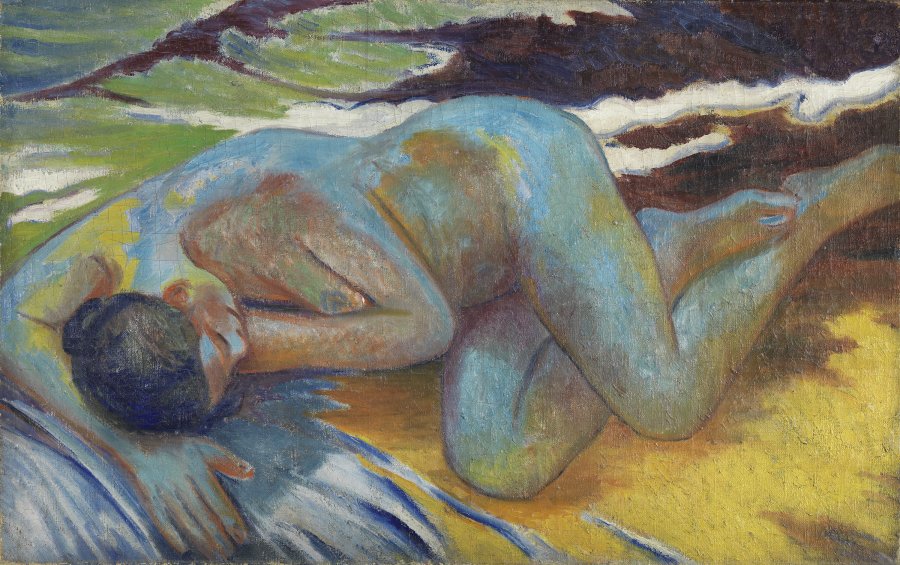

Mikhail Larionov

Blue Nude

ROOM 36

A common trait of certain avant- garde movements like Fauvism and Die Brücke, immersed in an idyll with nature at its purest, was the rise of the nude en plein air (the nudes of Müller and Kirchner in the previous room are excellent examples), which evoked a certain nostalgia for a lost paradise. These sentiments were partly aroused by Gauguin’s departure to the South Seas in search of exoticism and partly by the example of Matisse, whose simplification of the line and use of pure colours seem to transport us to an Arcadian golden age.

Larionov travelled to Paris in 1906, where he witnessed first hand the works of the Post-Impressionists and, soon after, the influence of Symbolism and Primitivism. During this period, Larionov frequently visited the home of Sergei Schukin, a rich merchant and passionate collector of modern art, who every Sunday would invite artists and intellectuals to his Moscovite house.

This Blue Nude was the Russian artist’s response to the paintings he saw at Schukin’s home, and indeed the collector introduced him to new directions for his art. His principal source of inspiration were the young Polynesian girls in the paintings of Gauguin who, like so many other artists, viewed extra-European cultures as places still untainted by the corrupting influence of civilisation and bourgeois morality.

Numerous painters and sculptors attempted to offer a new formal and symbolic interpretation of the figure of Eve (see, for example, Baranov-Rossiné work in Room N), but Gauguin is credited as the first one to reinvent her because rather than presenting her as a counterpoint to the figure of Adam, he often painted her alone or accompanied only by the snake.

In Diverses Choses (1987) Gauguin writes: “[She is] Eve after the Fall, still able to walk naked without shame, possessing all her animal beauty of the first day.” The painter would undertake a long journey, the last, to the Marquesas Islands to rethink the foundational myths of western civilisation and paint bodies without artifice, exhibited without shame for all to see, free of the guilt associated with Christian imagery. As the artist said in an interview, “To create something new, one must go back again to sources, to humanity in infancy.”

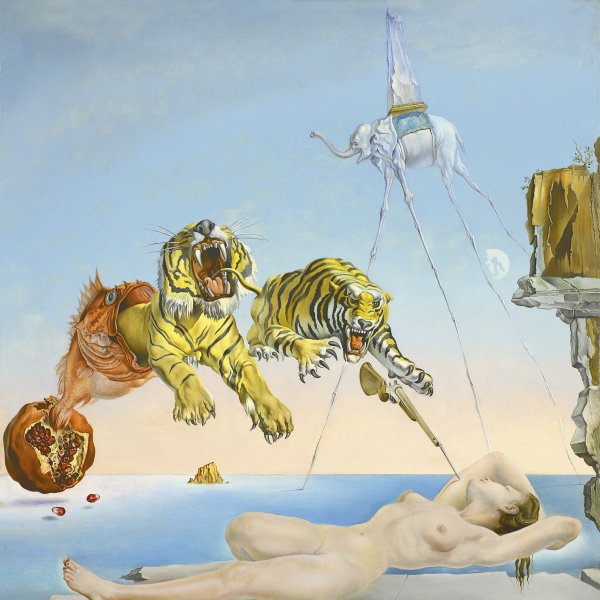

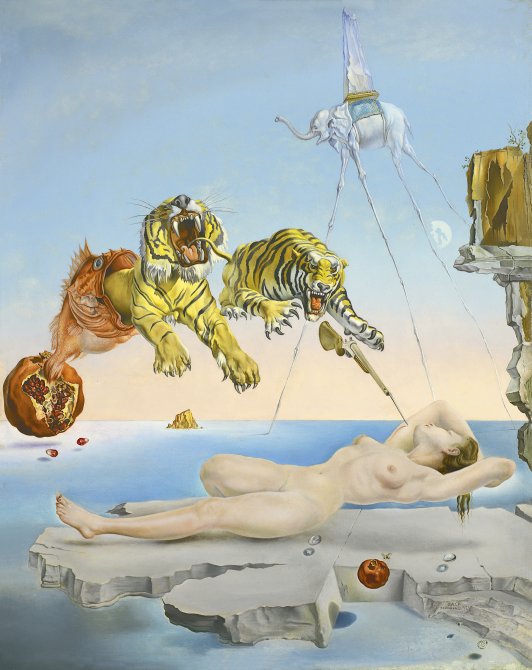

Salvador Dalí

Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second before Waking

ROOM 44

After the departure instigated by Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the subject underwent a process of formal disintegration that marked the definitive abandonment of classical models and led, among other things, to the mechanical interpretations of Léger (visitors may have noticed The Staircase (Second State) in Room 41), which in turn harked back to the dynamism of Duchamp’s famous Nude Descending a Staircase from 1912.

Following the iconoclastic revolt of Dadaism, in which the human body was barely insinuated by found materials and biomorphic forms, and the rejection of the Futurists, who in their Technical Manifesto of Futurist Painting of 1910 proclaimed, “[We fight] against the nude in painting, as nauseous and as tedious as adultery in literature,” the movement known as the “return to order” initiated a recovery of the classical nude, which in Surrealism found its place in dreams and the subconscious.

In the second decade of the century, the Surrealists started delving into the corporeal, into sexuality and the psychoanalytical implications of female/male polarity, not only in iconography but also in the creation of situations of a provocative or scandalous nature, openly exploring aspects like alienation, neurosis and perversion.

Dalí’s aim was precisely to make “hand- painted dream photographs” based on Freudian theories. In this work he returned to his “paranoiac critical method” inspired by psychoanalysis, which defended the view that images had multiple meanings open to several interpretations, to depict the body of Gala, his muse, immersed in a deep sleep from which she is about to be woken by the buzzing of the bee and the prod of the bayonet.

Paul Delvaux also created a unique pictorial universe steeped in dreams and poetry. His work may be interpreted as a permanent celebration of woman, be she Eve or Venus. He called these women with their large expressive eyes and whiter- than-white skin “extras”, beings without a history who sleepwalked amidst the ruins.

The overlapping of desire between the ego and the other, but also the impossibility of communication between human beings and their irremediable loneliness, are captured in the theme of the double, a recurring motif in the Belgian artist’s work. In the work on display in this room, Woman in the Mirror, from 1936, the mod el’s reflection does not correspond to reality; the person looking at the woman in the cave is the image in the mirror, not the other way around.

Delvaux attributes an active role to the mirror, as an instrument of knowledge, thus opting for imaginary reality as a supra-reality over and above the immediately tangible. The two strips of lace bear a resemblance to a snake’s skin, shed and renewed over and over again, but also to the legs of a sphinx. The face reflected in the mirror seems to pose an enigma, perhaps about the impossibility of knowing the truth, as Plato argued in the allegory of the cave. Meanwhile, the vaguely phallic entrance to the grotto could be an allusion to the petrification of desire, which is never satiated.

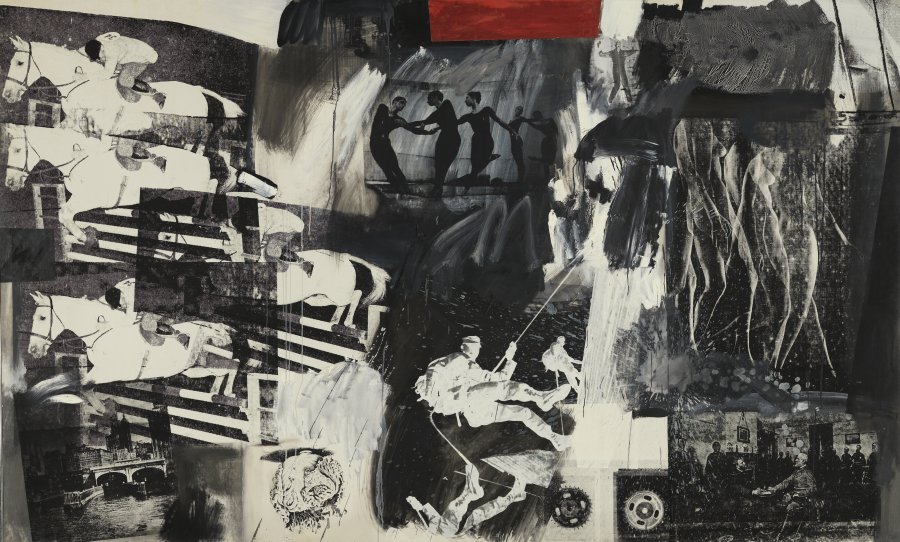

Robert Rauschenberg

Express

ROOM 48

Together with Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg provided a link between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. In the mid-1950s, Rauschenberg started producing his combine paintings, hybrid works that mixed painting with assemblage and collage, as if they were jigsaw puzzles or visual hieroglyphs. Later on, under the influence of Andy Warhol, he adopted a new technique—silkscreen printmaking—which enabled him to insert photographic images, mixing and superimposing them like collages on which he then applied oil paint in his characteristic expressive strokes.

It is to this group of paintings that Express belongs. The title and images reference movement and speed: the jumping horse, the climbers in their ascent, the choreography of the dancers—a tribute to the company of his choreographer friend Merce Cunningham—and the sequence of photographs of a moving nude woman, an explicit reference to the famous picture Nude Descending a Staircase by Marcel Duchamp, with whom Rauschenbert maintained a very productive artistic dialogue.

The divergence of Duchamp’s work with respect to the conventions that had hitherto governed the nude unleashed an avalanche of criticism. “A nude never descends the stairs—a nude reclines,” insisted his detractors, but for Duchamp it was precisely a question of doing a “nude different from the classic reclining or standing nude, and to put it in motion. There was something funny there, but it wasn’t at all funny when I did it.”

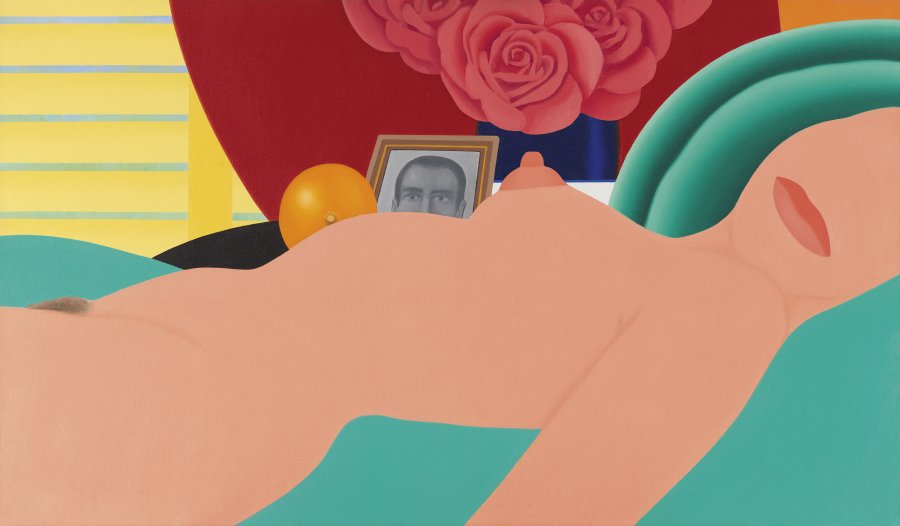

Tom Wesselmann

Nude No. 1

ROOM 52

Tom Wesselmann was one of the main practitioners of American Pop Art, along with James Rosenquist and Roy Lichtenstein, both represented in this room. Although Pop Art challenged Abstract Expressionism, Wesselmann always admitted that it was seeing Willem de Kooning’s Women series in 1953 that motivated him to begin his own series of Great American Nudes in 1961.

The Pop aesthetic treated the nude as just another consumer product of contemporary society. Indeed, a genuine obsession with the female body emerged, often reduced to a mere sign or anatomical detail. As time went by, these images became increasingly erotic, finally turning women into depersonalised sex symbols.

Wesselmann’s large-format modern odalisques in their flat inks combine the European tradition of the nude—which includes iconic works like Manet’s Olympia and the nudes of Matisse and Modigliani, whose exhibition at Galerie Berthe Weill in 1917 was shut down by the police on the grounds of “indecency”—with everyday elements and images of American pop culture borrowed from movies, the press and television. The inclusion of certain elements, as well as a photograph of the painter himself and an orange and a vase of red roses, turns this nude into an allegory of sensual pleasures. “It is the Playboy ‘Playmate of the month’ pull-out pin-up which provides us with the closest contemporary equivalent of the odalisque in painting,” declared another Pop artist, Richard Hamilton.

The absence of the face—where the subject’s intimacy is revealed, where the ego is disclosed—contrasts with the carnal handling of the model’s erogenous zones: the pubis, breast and lips. This type of depiction, splintered into short planes, tends to eclipse the subject, resembling a representational tradition more akin to advertising or porno movies because the explicit sexual content erases all mystery.

With no accidents to indicate the passage of time and no marks left by the life lived, the body is as flat, smooth and perfect as it is unreal, pure fiction, as befits a society in which the body has often become an object for display and consumption, subject to market forces and the marketing of appearances.