Nubla

By Ana Gómez and Clara Harguindey

This route proposes an exploration of the works that inspired the imagery of the video game Nubla.

The game is a “new” interactive medium for telling stories based on “new” virtual logics rather than conventional linear narratives. Nubla is a collaborative project developed by the museum’s Education Department that aims to draw connections between technology and art, creating dialogues and synergies from a creative, critical perspective. Therefore, the intention is not to conduct a thorough, conclusive survey of art history, but to find shared visions in it and generate stories, connections and new narratives.

Part of what makes this video game unique is the fact that it was designed inside the museum, and its settings and storyline are based on works in the collection. The game takes us on a journey through a universe where the death of creativity has made time stand still and memories fade. Identity, territory, the border, the city and dreams are just some of the themes used to articulate the game’s discourse and chart our course through the museum halls.

In this long-term creative laboratory, pictures are the benchmark and inspiration for all of the imagery and become challenges in the game. Touring and discovering the museum, identifying possible links between the video game’s storyline and painting, and making up stories that create visual and semantic connections between different artworks were some of the ideas that inspired and guided us in the process of developing this project. How the paintings are observed, imagined and associated with the game narrative is not determined by author or context; instead, it follows a freer, more transversal relational system, a process closer to that employed by Aby Warburg when devising his Mnemosyne Atlas or “Memory Atlas”, an extensive system of panels in which he sought to establish new kinds of associations between images from different contexts. Thus, we arrived at the premises of the scenarios and narrative by addressing and then thoroughly examining some of these works, proposing themes for contemporary reflection and thought that allow us to debate and share ideas

The game’s story begins in the halls of the museum, where five historical characters invite us to choose one of them and set off on a journey that will take us beyond the paintings. The mission: to visit places in a long-forgotten world and retrieve memories, the shards of life experience that were left behind. After this first part, the journey continues through other territories that no longer exist in dreams, places where time has stopped. Our characters, accompanied by Nubla, will face challenges, tests and enemies as they try to keep the creativity and memory of that world from disappearing forever.

Combining the classic visual language of painting with the most contemporary audiovisual technology (typical of interactive video-game narratives) is an interesting way to expand the knowledge stored in museums and transfer it to new media—and consequently to new audiences.

As an interactive audiovisual device, the video game can be a powerful tool for telling exciting stories. In a concrete fictional world organised according to specific rules, players will make their own decisions and determine how the story unfolds as an active participant, for we believe that the best way to learn is through creativity and empathy. Ratifying our own senses in small, seemingly foreign spheres of reality makes us feel that this reality affects and concerns us directly, forcing us to get involved and take sides.

In a process like that which unfolds in Nubla, it is interesting to see the obvious narrative potential of artworks, something we often overlook because we are caught up in the aura of the masterpiece or the artist’s technical prowess. Works of art are filled with people and places that spark our imagination: women lost in thought, sitting in a hotel room or at a vanity table, waiting for something yet to come; cities where all of the inhabitants are running in no particular direction; or small universes created out of broken glasses, discarded bits of wood and starfish. They all invite us to imagine stories, ask questions and invent possible answers and futures. This narrative capacity and spirit of discovery is something we want to make visitors aware of as they peruse the selected artworks, turning the museum into a place for weaving and sharing stories.

Starts on the second floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located.

Portrait of a Lady

Grien’s Portrait of a lady shows us an unidentified young woman of enigmatic gaze and beauty, with a round pale face, almond-shaped eyes and small, clearly outlined mouth. It is one of the few female portraits made by this artist. Historians have been unable to link the portrait to a specific individual, which suggests that it may be an idealised image or representation invented by the artist—a rather surprising notion if we consider the attitude and energy that Grien managed to convey through the character’s defiant gaze and hand gesture, with one finger bent and raised above the rest. Grien was a highly skilled German Renaissance artist who studied under Dürer, best known for his depictions of feminine allegories that reflect on life and death.

The intensity of the lady’s gaze recalls that of the great tragic biblical heroines like Salome and Judith, who may have provided the inspiration for this portrait. A comparison of this work with some of the female figures portrayed by Lucas Cranach the Elder reveals many stylistic similarities in the representation of the characters’ physical attributes and poses, as well as in the painstaking detail of the garments and jewellery. Grien’s nameless woman is not carrying a severed male head on a tray, but she does stare at us with Salome-like confidence and intensity, as if she were hiding something from the viewer.

That very gaze, serene at first glance and belligerent upon closer inspection, is an interesting topic to explore in a project like Nubla, which examines the theme of identity and representation through portraiture, with the paintings in the Old Masters collection as inspiration. In one of the first game scenarios, after crossing the museum threshold, we come to a place containing nothing but portraits hung on the walls. This “picture house” is a place where memory survives thanks to the fragmented recollections we discover as we draw closer to each of these portraits. The people we see in those paintings are part of the memory of Nubla’s vanished world, and since the occupants of the classic portraits are waiting for attributes or objects to complement their likenesses, our mission as players will be to find them. The genre of portraiture has always sought to preserve the memory of people over time, either by reproducing their physical and moral attributes in true-to-life detail, by creating idealised visions as in the Renaissance, or by capturing the person as seen through the subjective, free and even critical eye of the artist.

Easter Morning

Three women, seen from behind, walk down a winding lane amid gravestones indicative of a cemetery, inviting us to follow them. We can also see other small clusters of people who, with the women, form a silent procession under the denuded trees and the early morning moon illuminating the scene. As in other works, here Caspar David Friedrich draws us into the scene with his engrossed, slow-moving characters, observers and walkers whose size attests their frailty and smallness before the immensity of nature. The painter depicted a fragment of territory, a mental landscape imagined and inspired by his frequent strolls through the woods and fields of his native Germany, during which he made sketches and drawings from life that he later used to compose his landscapes, combining some of these impressions with more transcendental thoughts and questions to complete the works in his studio.

Friedrich explore the representation of nature and territory through emotions and feelings, as he explained in some of his notes: “I must surrender myself to what surrounds me, unite myself with its clouds and rocks, in order to be what I am. I need solitude in order to communicate with nature".

In Friedrich’s works, each element of the composition—the moon, the groups of women, the lane or the bare trees whose sprouting buds herald the advent of spring—are part of a symbolic construction in which all of these things are held together by an inner invisible thread, and that thread weaves other meanings beyond what the eye can perceive. His intention was to paint not a realistic landscape but an emotional one linked to his own subjectivity, to his innermost self, as his words remind us: “The painter should paint not only what he has in front of him, but also what he sees inside himself. If he sees nothing within, then he should stop painting what he sees in front of him".

Friedrich’s vision is related to the artistic sensibility of Romanticism, characterised by a sense of angst and breathless awe before the immensity of humankind’s natural surroundings and a sentiment and wonder very close to the idea of “sublime beauty” as expressed by thinkers like Immanuel Kant or Edmund Burke. As Burke wrote, “Astonishment [...] is the effect of the sublime in its highest degree; the inferior effects are admiration, reverence and respect.” He then goes on to speak of mountains, precipices and the splendour of the starry heaven, noting that “infinity has a tendency to fill the mind with that sort of delightful horror, which is the most genuine effect and truest test of the sublime” and recalling the sublime terror inspired by “vacuity, darkness, solitude and silence”.

In the Nubla narrative, this work serves as the basis for exploring the relationship between nature and emotions such as solitude, emptiness and waiting. Thus, passing through a dense forest we reach an intermediate area which, as in Friedrich’s painting, contains tombstones bearing the names of Romantic painters. We then encounter the group of three women, who have been turned into a stony structure and block our path. The skeletal trees recreate the desolate atmosphere of the landscape in the Romantic picture, and the moon, which as in Friedrich’s work announces the end of night and the coming of day, will be the key to advancing in the game. At this point in the story we will need to use a brush to erase the moon and make the stone figures disappear, leaving the landscape devoid of any human trace.

Continues on the first floor

On the map you can see the rooms where the masterworks are located

Expulsion. Moon and Firelight

Thomas Cole, a european painter who immigrated with his family to the United States, painted this allegorical scene based on the biblical story of the Expulsion from Eden when he was just 27 years old, revealing his fascination with the wild American landscape.

From a very young age, the artist roamed across America and discovered the contrasts of its stunning landscapes, from the picturesque banks of the Hudson to the wide-open plains and the White Mountains, producing countless sketches that would later form the basis of his surprising artistic imagery. A painter, poet and essayist, Cole transports us to a unique universe where the violence and tragedy of nature coexist with the peace and tranquillity of images that seem to recreate paradise. This aesthetic ambivalence or clash of opposites give his landscapes an allegorical meaning and moral depth that made their author one of the most important landscape artists of American Romanticism. In Expulsion: Moon and Firelight, a stone bridge spanning the abyss, with a large waterfall and an erupting volcano in the background, offers the only way out, the road to expulsion in a scene devoid of human figures. Here Cole recreated the Expulsion from Eden without depicting Adam and Eve, making nature the sole protagonist of the scene.

In the game, Thomas Cole’s canvas is the inspiration for the final part of the level that begins with the harbour and references to Dutch seascapes at the museum and continues with settings based on European and later American Romantic landscapes. This level is a reflection on the representation of territory in art history, at a time when landscape depictions began to move away from the idyllic, allegorical and often unrealistic visions of earlier centuries and instead reflect the artist’s subjective, first-hand perception of nature, edging closer to contemporaneity and its new interpretations.

In the video game, Thomas Cole’s epic, quasi-visionary landscape is translated into a large rocky cavern. Orographically, the cave materialises cracks in the earth, symbolising the first days of creation and the idea of origin. At the same time, it recalls the caves that served as both shelters and canvases of the symbolic universe of the first humans. Inside the cavern we will find a mechanical automaton guarding the gateway to the world of dreams, the next level in the game. The automaton is made of bits of metal and found objects, and in order to activate it we will need to play with the light and the different natural elements we find along the way.

The Corner House (Villa Kochmann, Dresden)

Meidner painted The corner house as part of a series of apocalyptic cityscapes in which he portrayed different cities, real and imaginary, dominated by an ominous, troubled atmosphere. In his cities, people and animals run and the buildings look ruinous, on the verge of collapse and seemingly shaken by an internal force and energy coming from some unidentified source. His work denotes the influence of avant-garde movements such as Futurism, with its idea of the dynamism and destruction of the modern city, or Cubism, with its spatial ruptures. In The Corner House, Meidner attempted to symbolically portray the house’s owner, Franz Kochmann, proprietor of a liquor store and a lithography workshop. It is a house on the cusp of the Great War. The house and its portrait, undoubtedly painted from sketches drawn in situ at nightfall, are pictorially rendered in broad brushstrokes and dark bluish hues.

Meidner’s work is the inspiration for the Blue City in Nubla, a devastated place in constant transformation, like the artist’s city paintings. The Blue City is breaking apart and constantly changing: fragments of houses hang in mid-air and architectural structures twist and turn inwards. In this wasteland, after overcoming various challenges, we finally meet Nubla, a dreamlike elephant that we must rouse from slumber in order to continue our journey.

As in the portrait of Villa Kochmann, this is a city without inhabitants; only the architecture and the objects speak. We might intuit their presence from the windows that seem to be on the verge of shattering, the shadows behind the curtains or even the objects that appear in different parts of the game, presumably abandoned by their owners. Suitcases, letters and gloves are just some of these fragments of memory we find in the Blue City.

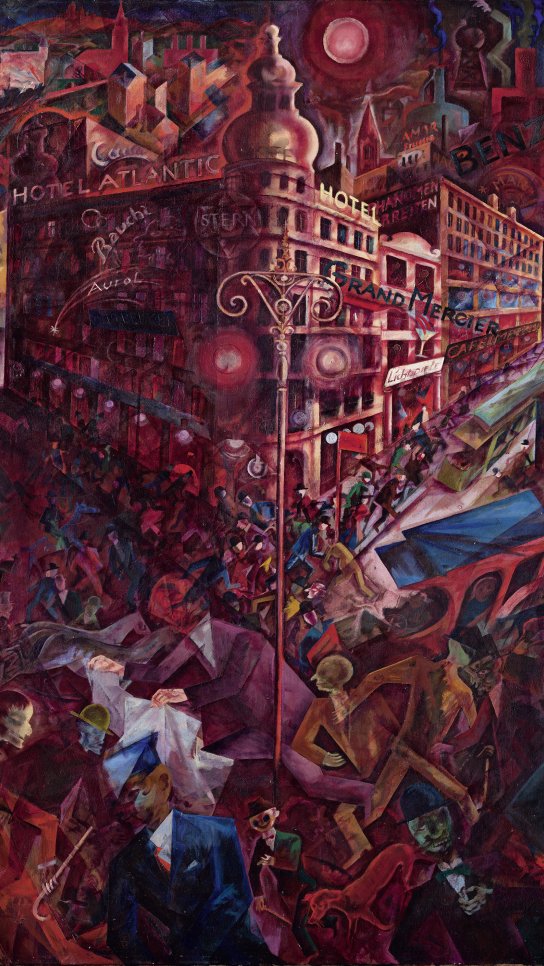

Metropolis

In Metropolis, Grosz offers a critical, warped vision of the city of Berlin during the Great War. It is a subjective portrayal of the city and its desperately fleeing pedestrians where only the buildings—the imaginary Hotel Atlantic in the centre of the composition and the lampposts, lights, signs and other urban elements—seem to lend coherence and stability to the chaotic scene.

This canvas is considered one of Grosz’s expressionist works, a vision of the modern metropolis as a nightmarish world of destruction. George Grosz had to abandon the work for a few months to fight in the war. The traumatic experiences of those months can be felt in every fragment of this piece. The deformed features and cartoonish quality of his characters and his liberal use of colour, clearly dominated by reddish tones, creates a hellish atmosphere. Stylistically, this work pertains to the artist’s expressionist oeuvre, but in it we can detect other artistic influences that were also part of Grosz’s creative language in those years. The impact of Cubist and Futurist aesthetics is patent in the spatial ruptures and strained perspectives of the buildings, as well as in the dynamic accelerated pace of the crowds, the hearses and the trams depicted as a procession leading nowhere.

During those years, judging by the painter’s memoirs, Grosz joined the avant-garde and frequented the most subversive artistic venues in Berlin, convinced that art was the fiercest weapon of all. A restless walker and compulsive draughtsman, he sketched in the street and filled his notebooks with portraits of Berlin society and decadent living. Prostitutes, bourgeoisie, beggars, mutilated war veterans: these vague characters with blurry faces make us reflect on human selfdestruction and the consequences of war.

In Nubla, Grosz’s Metropolis inspired the design of the city of M. This city is a composite of cities from different eras depicted by different artists, but the apocalyptic redtinged atmosphere of Metropolis was used to define several of the city scenarios in the game as well as many of the characters which, as in Grosz’s painting, are lost and running from some nameless threat. In the game, informed by some of the themes implicit in the German artist’s work, we reinvent a city that poses questions about how we dwell in cities, human relationships and their frailty, or the projection of power and politics in our societies.

M. is a captive city where those who have managed to enter have lost part of their memory. In this city, time stands still. As players, we will meet its inhabitants and help them to recover their memories and set time in motion again. We will encounter characters based on works at the museum, artists and important 20th-century philosophers like Walter Benjamin, who will help us to retrieve the inhabitants’ lost micro-stories. We will also find George Grosz, whose caricatures and drawings plastered on walls throughout the city will give us the clues we need to destroy the system that has paralysed M. To complete our mission, we must find the artists who live in the city and, like Grosz, believe in art and action as the only possible means of liberating M.

Solitary and Conjugal Trees

The german artist Max Ernst studied art, philosophy and psychiatry at Bonn University. He started out as a self-taught expressionist painter but, like many of his contemporaries, he rejected the bourgeois values that had led to World War I and joined the Berlin Dada group in 1918.

The following year, he was one of the leading promoters of the Cologne Dada group. He moved to Paris in 1922 and became acquainted with André Breton’s Surrealist group, producing paintings with semi-automatic methods like frottage.

In 1938 he moved in with Leonora Carrington. Together they rebuilt a house, filled it with reliefs and paintings and revelled in their idyllic creative retreat. However, that creativity was cut short when World War II began: Ernst was sent to prison, and upon being released he found himself alone; Leonora had suffered a bout of severe depression and been committed to a psychiatric hospital in Spain.

Christopher Green makes a beautiful connection between this work and Leonora Carrington’s novel Little Francis, written in 1937, especially the passage that reads: “I used to know a man who passed his whole life making the landscape into a zoo [...] He worked for years making rocks into lions and tigers, cabinet ministers, centaurs, historical characters, etc. He was a charming fellow but worked too hard. I think cypress trees are delightful, they remind me of wigs, and as they usually grow in cemeteries one imagines some beautiful lady’s death’s-head underneath.”

Like many other artists and intellectuals whose European homes were torn by war and devastation, Ernst decided to immigrate to New York, where he married the collector Peggy Guggenheim.

The artist said that his work was like his lifestyle, “not harmonious in the sense of classical composers, or even in the sense of the classical revolutionaries. Rebellious, heterogeneous, full of contradiction, it is unacceptable to specialists of art, culture, conduct, logic, morality.”

He painted Solitary and Conjugal Trees before departing for America at a time when his style was starting to take a new direction, moving from devastated cities to ghostly landscapes filled with bizarre figures. These landscapes were made using a semi-automatic technique known as decalcomania, in which paint is haphazardly applied to a smooth surface and later pressed against the canvas.

The cypress trees, riddled with hollows, faces and bodies, form a paradoxical dual landscape. In this double vision, the dreamlike and the terrible merge. The cypress, long a symbol of graveyards and death, has come to life.

This work gave us the idea for the Nubla greenhouse. The stillness of the empty forest is an ominous peace. The beauty of the woods when they are inhabited only by moonlight and objects of memory has a latent duality. In the process of constructing landscapes in the game, the subtle dualities of the everyday come to light: hidden beauty is revealed and the alarm begins to sound.

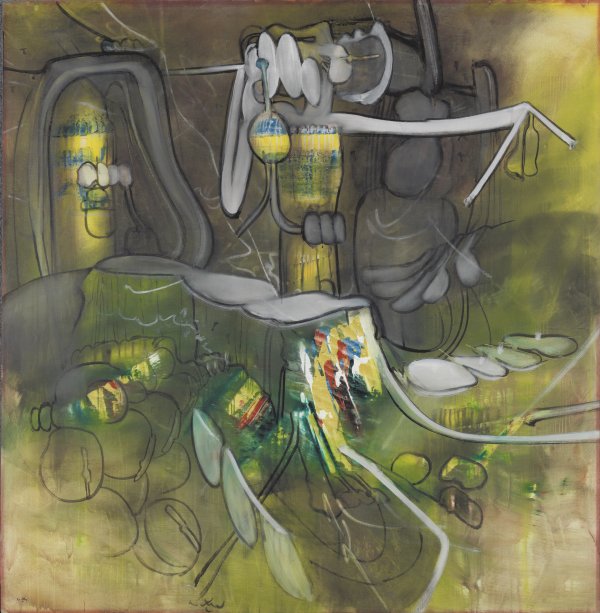

The Dazzling Outcast. From the Cicle: The Dazzling Outcast

Matta, trained as an architect, taught himself to paint. In 1931 he left Chile to work at Le Corbusier’s studio in Paris. There he met Neruda, and when he travelled to Spain three years later he came into contact with Lorca and Dalí. In 1937 he became acquainted with André Breton, who took an interest in Matta’s subjective fantasy landscapes and invited him to participate in the Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme. That event marked the beginning of Matta’s ten-year involvement with the Surrealist group.

Like many other creative Europeans, when World War II began Matta moved to New York, where he got to know artists like Jackson Pollock, Arshile Gorky and Mark Rothko. His pieces gradually grew larger after his trips to Mexico, where he discovered the work of the Mexican muralists, and that increase in scale influenced his American friends.

After his self-imposed exile in New York ended and he returned to Europe, Matta began to distance himself from Surrealist ideals until they eventually disappeared from his work. Even so, his creations retained a trace of the Surrealist spirit in the automatism typical of the new abstract languages. Matta wanted to raise social awareness through his pictures. “My paintings,” he wrote, “are an example of the conflict between the need to change the world and other people’s lives and the need to change my life.”

There is only one way to reach M, the city at the centre of the world. Although there may be many roads, all pass through the world of dreams. The oneiric, the surreal, the hallucinatory—this is the breeding ground of creativity and, consequently, of art. In a text written in 1965, Matta stated that the artist is a disavowed creature whose duty is to stir viewers’ consciences. Uneasy and puzzled, they will want to understand the painting and, when they attempt it, the painting will possess them. Thus, trapped in a confusing situation, spectators will be forced “to perform a poetic act of creation in order to claim the work for themselves: besieged by the real, they feel defeated, and that makes them think.” “This act of liberation,” Matta wrote, “may grow stronger in them little by little until it becomes a revolutionary attitude.” The ultimate aim of the artist’s work is therefore to turn his viewers into thinking beings that carefully examine the world around them, in order to live and understand life in a way that is “clearer, more lucid. More beautiful.” The artists who live in M are the conscious minority, an isolated, hidden group that nevertheless conducts exercises in resistance.

The dream-world settings are based on this series of five canvases and their cosmic, spatial, organic aesthetics. The way the canvases are arranged to form a kind of box invites viewers to dive into and mingle with their stimulating forms which, as Marcel Duchamp noted, open our eyes to “regions of space until then unknown in the field of art”. Players also become spectators and thinking beings as they find themselves drawn into the world of Nubla and its conflicts.

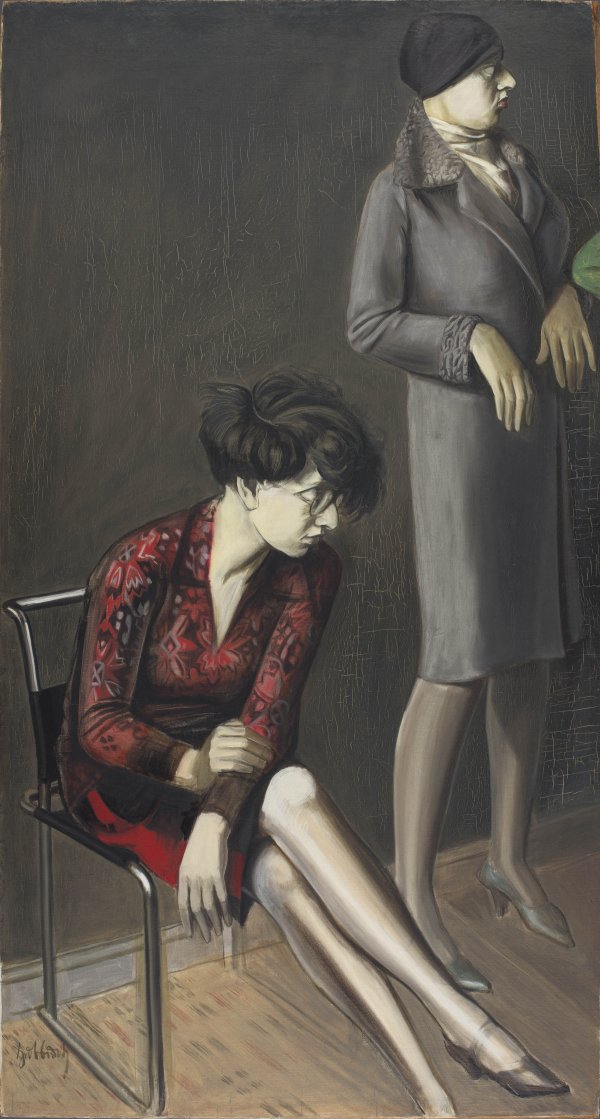

Twice Hilde II

For Karl Hubbuch, art was a means of expressing a critical view engaged with the society of his time. This is hardly surprising, considering that he belonged to the generation of artists who witnessed (or survived) two world wars and their aftermaths. He lived in a devastated, fascist Europe. Hubbuch was born in Karlsruhe, Germany, and began attending art school there, where he became friends with Rudolf Schlichter and Georg Scholz. When he studied graphic arts at the Kunstgewerbemuseum in Berlin, George Grosz and Oskar Nerlinger were among his classmates. All three subscribed to the radical ideology of the Novembergruppe and Rote Gruppe and later joined the circle of artists who advocated the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity). The New Objectivity movement was a reaction against expressionism. To its proponents, embracing individual expression and a subjective worldview seemed like an escapist, thoughtless, irresponsible attitude in light of Germany’s dramatic situation after the crushing defeat in the Great War. They believed that the individual should become collective, rejecting the bourgeois society of exploitation.

Despite their radical stance against the establishment and the political context, their pictorial style was moderate. In consonance with the proponents of this German New Objectivity, Hubbuch showed a predilection for portraiture and meticulous renderings of the objects and textures that construct and comprise people’s everyday lives.

Twice Hilde II was initially conceived as a quadruple portrait. After a leak damaged the central area of the work, the artist had to cut the canvas in half. This work is a double portrait of Hubbuch’s wife, Hilda Isai, who was one of his drawing pupils at the academy in Karlsruhe and later left him to pursue photography at the Dessau Bauhaus. Instead of capturing Hilde’s personality in a single portrait, Hubbuch decided to paint different figures that reflect his wife’s multifaceted identity, from the serious intellectual sitting on a tube chair by modern designer Marcel Breuer to the sensual woman in underclothes at the opposite end of the composition, part of the other double portrait now in Munich. In the process of creating Nubla and filling our city with inhabitants, we wanted to reveal identity-related games as political games seen through a slightly critical lens. Dualities define us as people. Our goal was to understand the distance between “self” and the “other”, to distinguish between the “self” that constructs the city and the “self” constructed by the city in which we live—to dwell in our contradictions. Like Hubbuch, we wanted to search the ordinary for those contained forces that allow us to be or prevent us from being, the forces that make us migrants or emigrants, characterise us as men or women and tell us whether we are young or old. We wanted to disentangle all of our potential facets. Hilde strolls through the streets of the city of M and tells us about the possible identities erected with symbolic matter on the foundation of memory, generating new relationships and perceptions of the familiar.

Hotel Room

In a 1961 interview Hopper quoted Goethe’s description of literature, which in his view also applied to painting: “The beginning and end of all literary activity is the reproduction of the world that surrounds me by means of the world that is in me".

Accustomed to life in a small Victorian town, the transition to the infinite, impersonal, alienating reality of New York City was a defining experience that would inform one of the central themes of his oeuvre: loneliness. His work Hotel Room is an obvious source of inspiration for the time- and memory-deprived universe of Nubla. The cold, starkly unpoetic overhead light source illuminates a woman perched on the edge of the bed, perusing a piece of paper. We know the paper is actually a train timetable thanks to the notes made by Hopper’s wife, Josephine Nivinson who, in addition to posing for this and many of his other paintings, kept exhaustive records of the painter’s work. In this respect, the work’s narrative potential is quite curious. In his essay on Hopper’s work, the poet Mark Strand interpreted the paper in the woman’s hands in a more poetic light: “The way the woman in Hotel Room is sitting on the edge of the bed, slightly hunched over, along with the way she holds the timetable with her hands resting on her knees, suggest that she has read it before, perhaps many times before”—and the information it contains is not good.

The diagonals of the composition (whose vanishing point is the window, telling us that it is night-time), the flat colours and the contrasts of light and shadow enhance the dramatic quality of the scene. This drama invites the viewer to invent a before and after, a story that envelops the depicted moment as if it were part of a flowing life course.

This suggestion remains implacable in all of his works, subtly appealing to our daily absences and enigmas, our private solitudes and silences. The silences that Hopper paints seem unbreakable. The artist casts us in the role of voyeur subjects, but we do not actually enter the scene, for the young woman’s reverie has made it immutable.

What do we know about her? Her figure offers few clues; she is only half-dressed, and her anodyne face tells us little of her emotions. Nor can we deduce her identity from the hotel room, a room like so many others, a “non-place” typical of contemporary society. However, we can piece together her story from her personal belongings.

When creating the territories and identity of the Nubla universe, we felt that this work in the collection was indispensable. In order to translate the message conveyed by Hopper’s painting into “gameplay”, we had to break down the work and find meaningful elements to use in our mechanics. If our world is uninhabited, how can we indicate that it was not always so? How can we communicate this new solitude? The answer lies in the young woman’s things.

We find a key under one of the suitcases in the room, open the window, and the rain falling from a cloud pours inside, flooding the room. The young woman’s belongings become platforms that allow us to reach what we need to continue playing. This device aims to convey an emotion and a poetics similar to that of the artist, activated through interaction with the space.

Blue Soap Bubble

Cornell was a shy, solitary man who became interested in art in the 1920s.

He visited numerous contemporary art shows, and in 1931 he discovered the Julien Levy Gallery, where an exhibition of collages by Max Ernst had just opened. Shortly afterwards Cornell showed his own work to Levy, who introduced him to Marcel Duchamp and other Surrealist artists of his day. Cornell’s works were included in the first exhibition of Surrealist art in New York, but he never felt fully integrated in the group, as he was not interested in exploring sexuality or the subconscious in his art. Soon he had his first solo show at Levy’s gallery.

Cornell spent his life in a modest home in Queens, where he compulsively collected countless objects and used them to create visual poems in small glass boxes. At first he recycled boxes, but later, between 1932 and 1935, he learned to work with wood and build his own boxes with a neighbour’s help.

Cornell used these glass bells to build highly subjective artefacts whose meaning is hard to decipher. The compositions turned found objects into symbols of his desires and memory. His goal was not to turn commonplace detritus into art (as the Dadaists did) but to transform it into symbols and language.

In Nubla, memory is pieced together from the lost possessions and recollections of those who inhabited the territory in the past. In the player’s hands, these lost items become found objects and symbols, memory and desire.

Blue Soap Bubble is one of a series of early boxes inspired by the artist’s childhood memories. It is related to the 1936 piece Soap Bubble Set, his first box, which Alfred H. Barr included in Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism, the famous exhibition held at the Museum of Modern Art that same year. The possible meanings of the work have been elucidated by Diane Waldman. The blue drawer, star and sand undoubtedly allude to the sea. The metal hoop may represent the moon, which governs the ocean tides, but it might also refer to the ring that children use to blow bubbles. And the four cylinders recall the four members of his family. As in most of Cornell’s works, the back of Blue Soap Bubble includes a collage of pages taken from a printed Italian text.

Cornell also made films using experimental collage techniques reminiscent of dreams. Apparently Dalí was in the audience at his first screening. The Spanish artist accused Cornell of stealing his idea to combine collage techniques in films and said that he should stick to making boxes. This was a traumatic experience for the painfully shy and sensitive Cornell, who rarely showed his films after the event.

The combination of dreams and memory is a constant that unintentionally shapes the world of Nubla. This work was integrated quite simply in the form of a puzzle, a rearrangement of oneiric symbols that, once completed, will allow us to continue our quest, creating brandnew architecture, new relationships and new perceptions of the familiar. Like any audiovisual narrative, the video game is an order of symbols that constitute syntagmas of memory, through which desires are projected.

Tour resources

The order of the works in this pdf may differ from the recommended order.